The Ancient Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead and their Exciting Interpretation in Illumination

In the 13th century, French ephemeral poetry produced an amazing narrative. It tells of three nobles - a duke, a count and a king - whom God wanted to remind of their mortality. Because they gave too much to their status symbols and led extremely lavish lifestyles, God held up a mirror for them: they appeared as three dead men whose rotten and worn skeletons were a horrible sight.

To the facsimile

“What you are, that we were. What were are, that you will be”

While two of the nobles reacted with disgust and fear, the third understood God's purpose. The dead were once nobles too and admonished the three living that in death and before God all people were equal. In the hereafter it was not a matter of status and wealth, but a godly life full of humility and modesty that mattered.

Therefore, the dead reminded the nobles of the inevitability of death that overtakes everyone - even young people would not be immune from this. This gruesome vision of the future was intended to remind the living of the really important things - namely provisioning for the afterlife through a sinless existence.

The Depiction of the Legend in Illumination

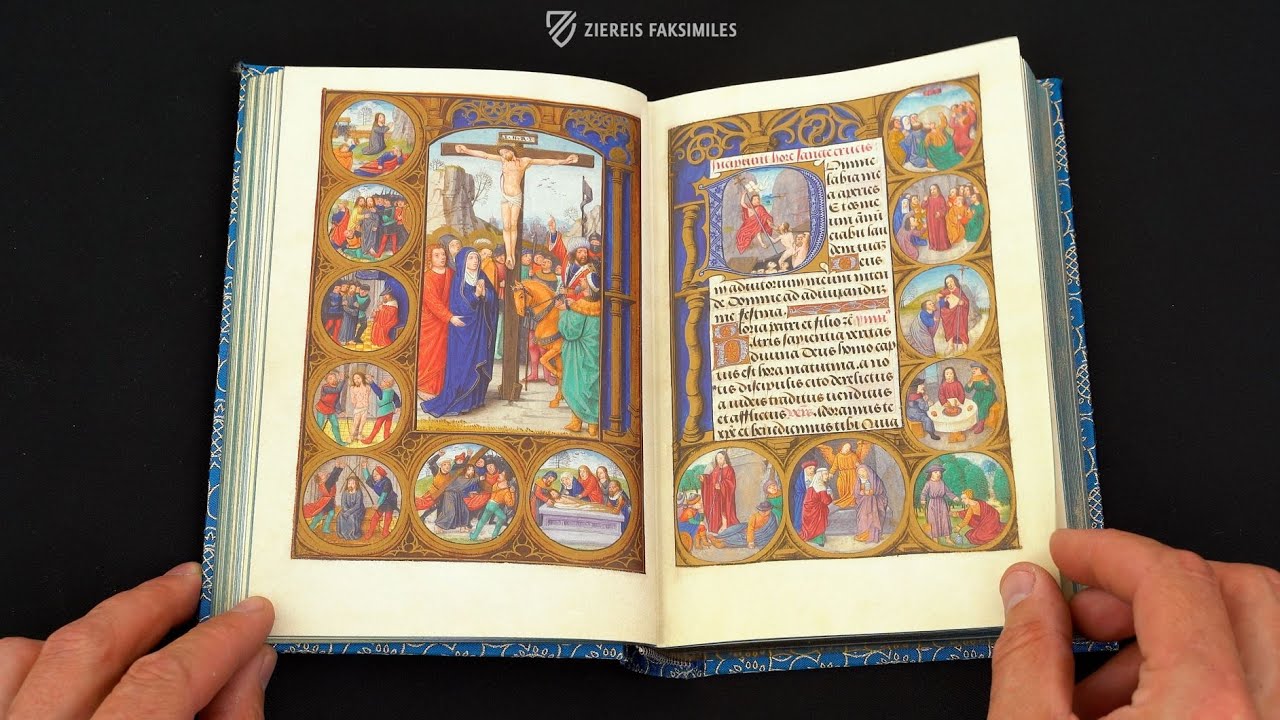

Since the legend was aimed at aristocrats, it is not surprising that it can be found above all else in the images and text of precious manuscripts. The subject was used in particular for the illustration of funeral offices and prayers for the dying, which can be found in most prayer and hour books of hours. Up until the 16th century, numerous illuminators, mainly French and Flemish, came up with different variations of the depiction. So, let's take a look at our facsimiles!

To the facsimile

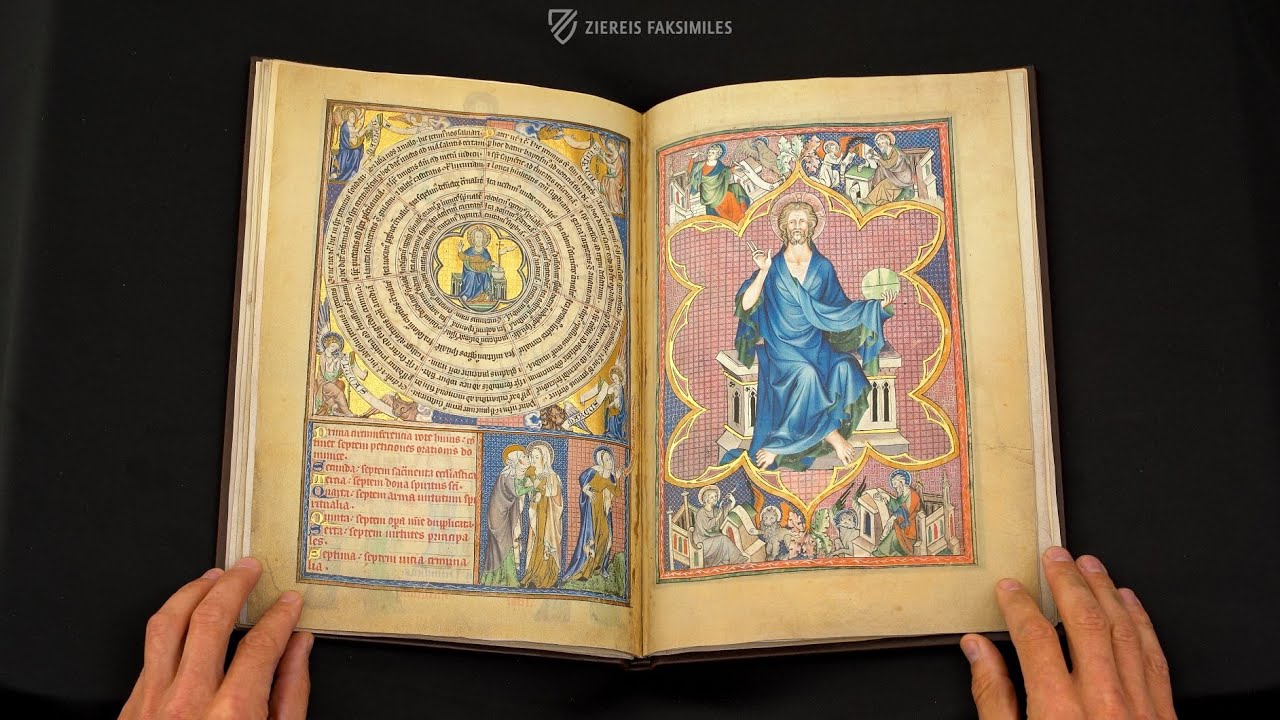

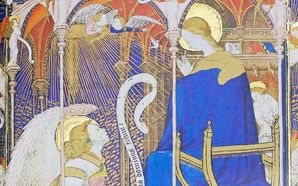

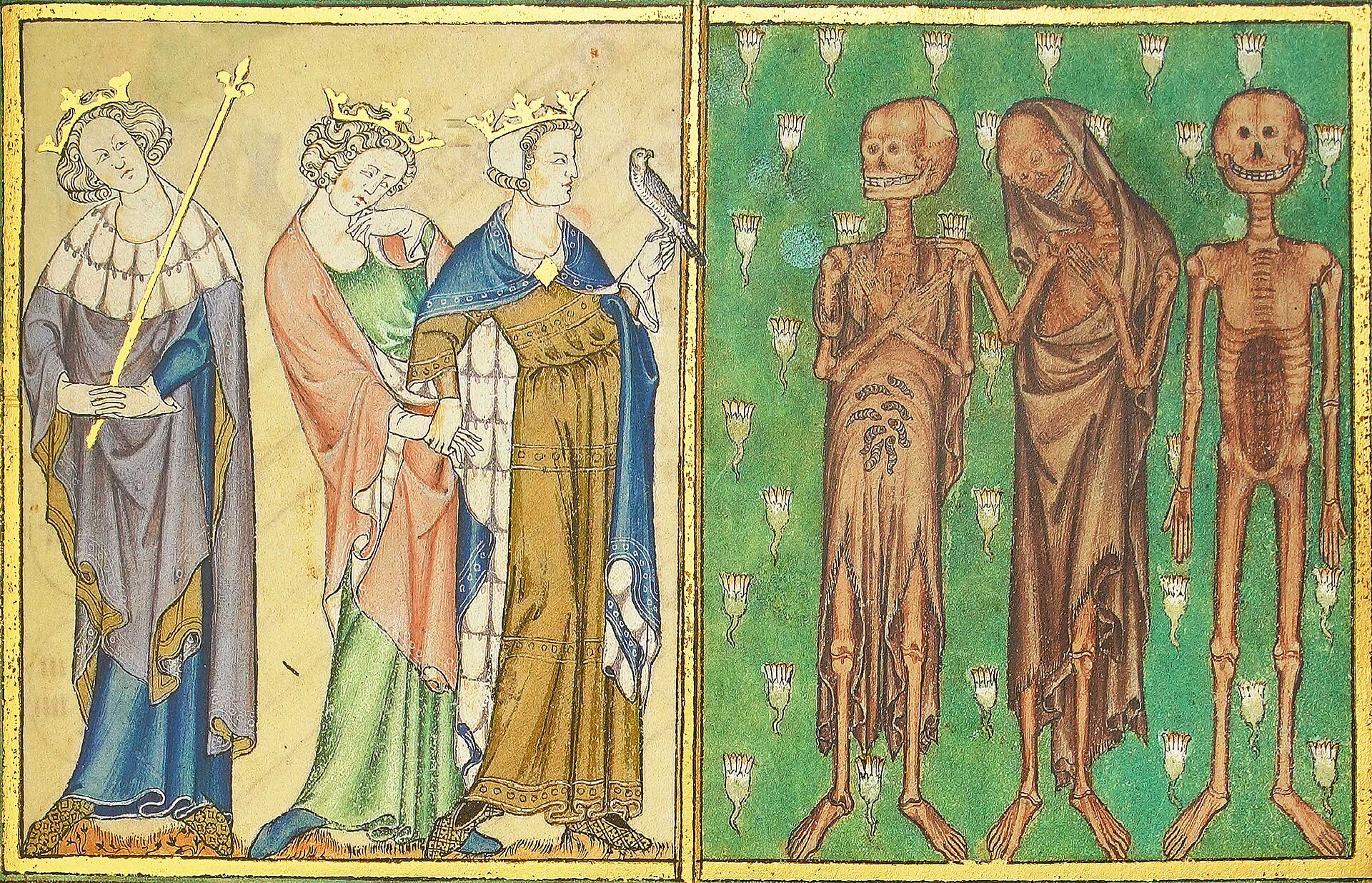

In the splendid De Lisle Psalter, originating ca. 1310-20 in Westminster (United Kingdom), three crowned noblemen, one even with a valuable hunting falcon on his arm, are strictly compared to their decayed counterparts. The central axis serves as a mirror through which the aristocrats can view their less optimistic future on the right. The bodies of the dead clearly show different stages of decay.

To the facsimile

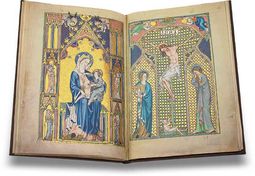

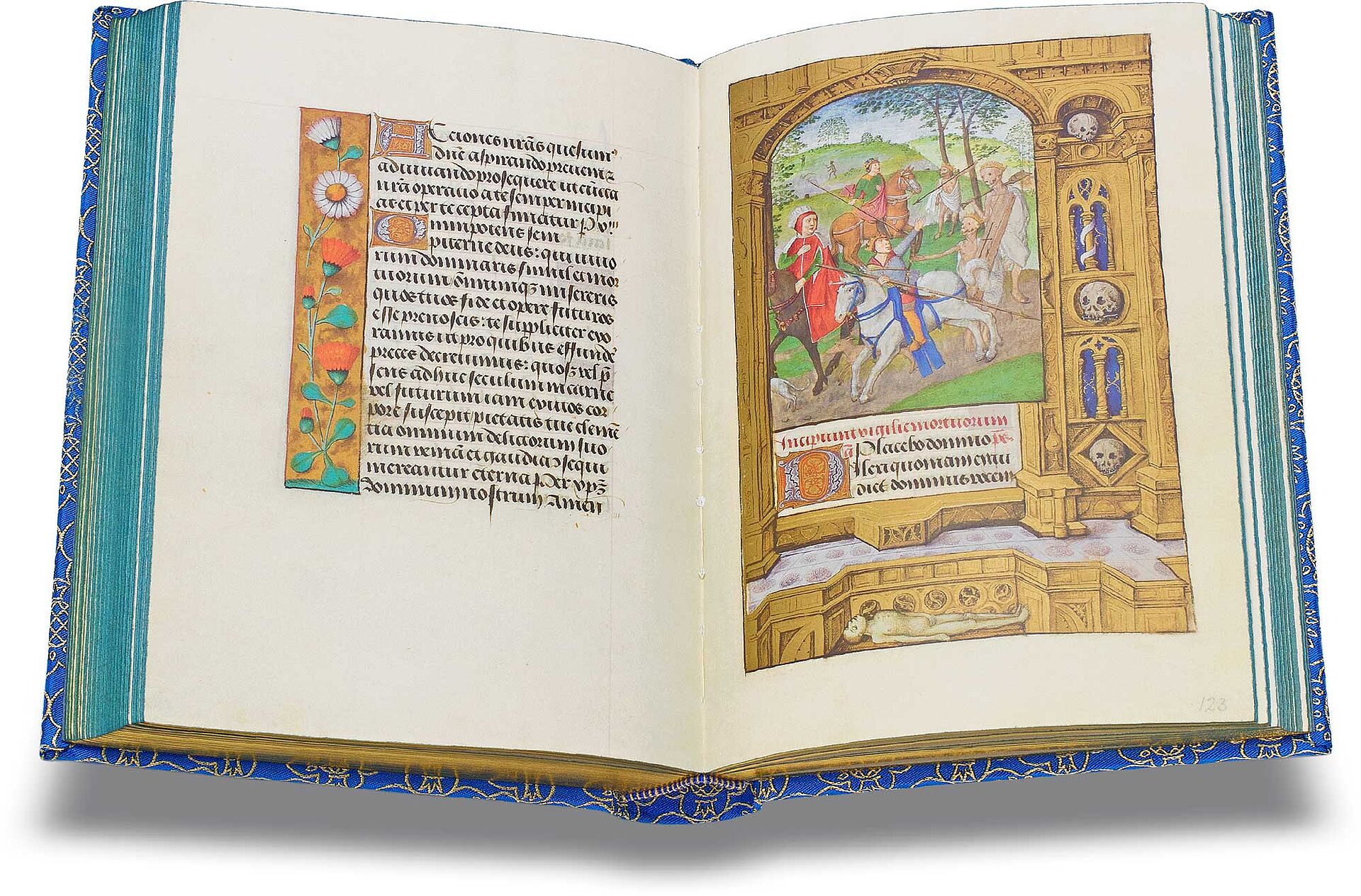

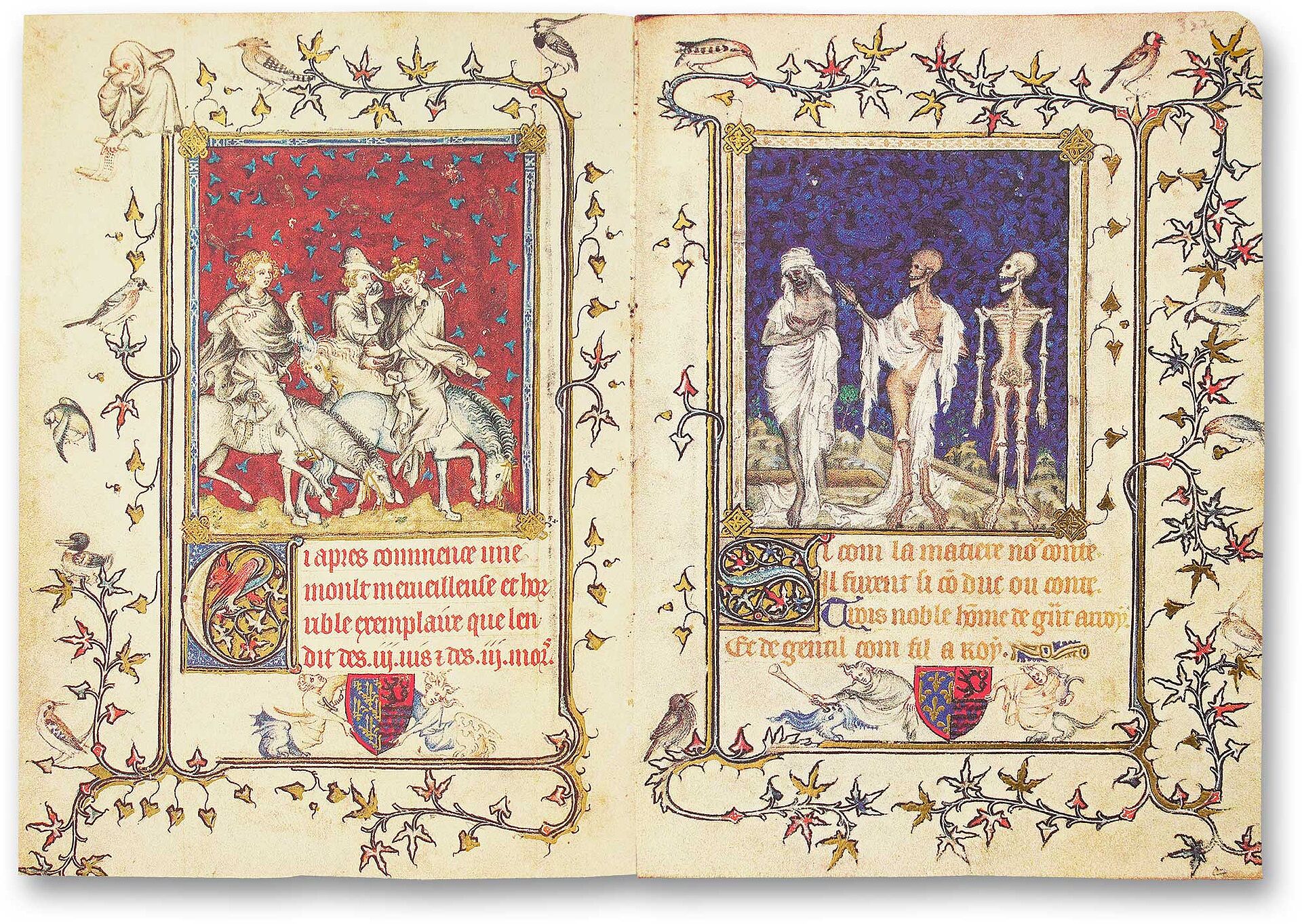

Over time, books of hours became popular "accessories" for aristocrats that emphasized their noble rank. In the Psalter of Bonne de Luxembourg, written in Paris before 1349, the mounts react to the speaking skeletons at least as skeptically as their riders. Additionally, the dead are in a suitable location: a cemetery.

To the facsimile

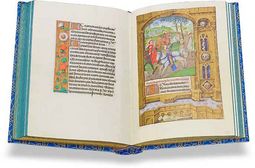

At the end of the Middle Ages, the depictions became more and more dramatic and the living sometimes became the hunted in the dynamic scenes. Both the miniatures in the Berlin Hours of Mary of Burgundy and the Fitzwilliam Book of Hours (above) show the unexpected clash in front of lush, green landscapes. The nobles are surprised, as it were, on one of their exclusive hunting trips. They flee on their horses from the dead armed with spears who even have a coffin ready in the Fitzwilliam Book of Hours.

In the Early Modern Era, the traces of the legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead, whose place would be taken by other depictions of impermanence such as the dances of death, were ultimately lost.