The Plantagenet Dynasty, or: How the Norman Kings of England Shaped the Island Country into the Richest and most Powerful Monarchy in Europe

Fourteen Plantagenets sat on the English throne; their dynasty lasted more than 300 years and was one of the most successful, transformative, and infamous in the history of Britain. The word Plantagenet originates from a nickname for Count Geoffrey d’Anjou (1113–51), a great warrior who supposedly wore a sprig of broom with golden flowers in his cap – Planta Genisteae. He was married to Empress Matilda (1102–67), widow of Holy Roman Emperor Henry V and daughter of King Henry I of England in 1128.

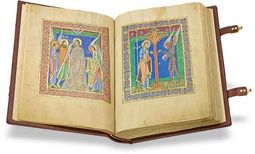

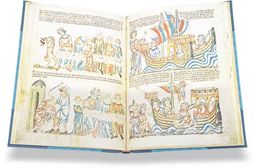

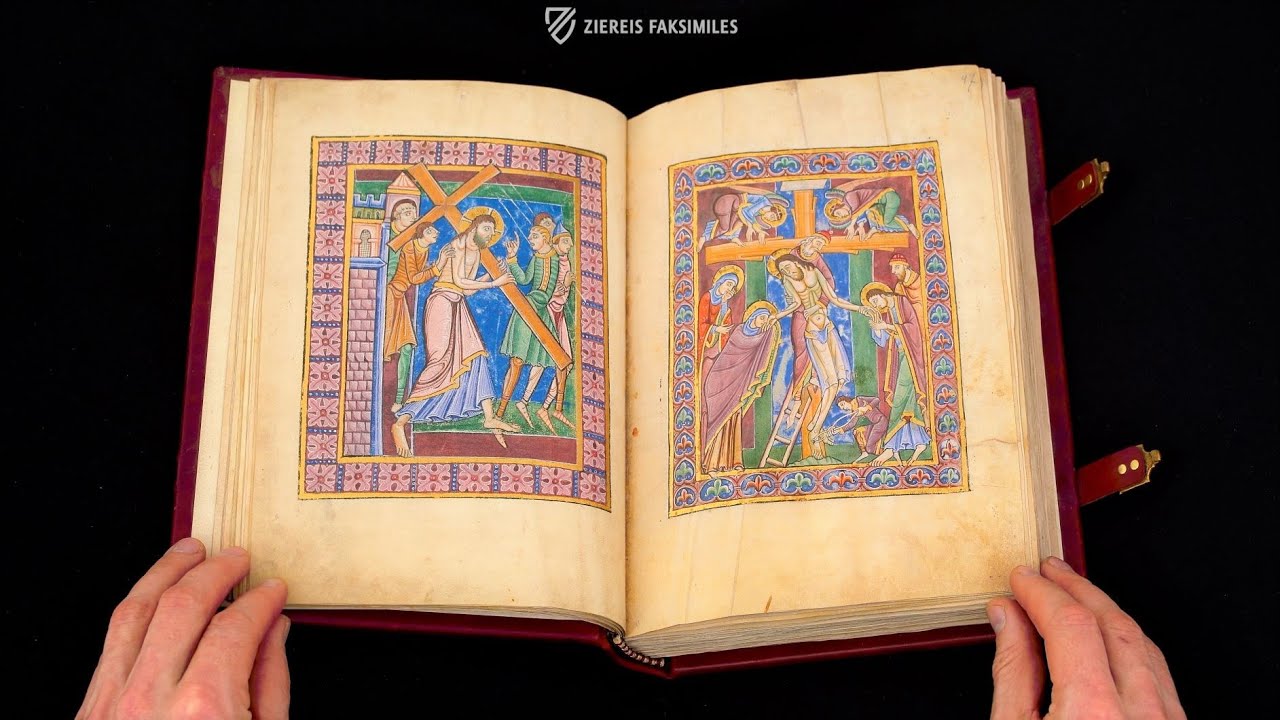

A succession crisis and terrible civil war known as The Anarchy followed the death of Henry I in 1135 and continued until 1153, when their son was finally recognized as rightful heir to the throne. After his coronation in 1154, Henry II (1133–89) restored peace and order to a weary realm and founded a dynasty. Meanwhile, the so-called Channel school emerged in the Plantagenet lands in England and Northern France, which yielded some of the finest masterpieces of Romanesque art, such as St. Alban’s Psalter and the Winchester Psalter.

Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine

To the facsimile

King Henry II of England was arguably the richest, most powerful, and most ruthless sovereign of the 12th century. His coronation marked the end of the strictly Norman dynasty established by his maternal great grandfather, William the Conqueror, the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty that would rule England until 1485, and the creation of the so-called Angevin Empire, a nod to his roots in Anjou, which stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenes Mountains.

Henry’s legal reforms are the basis of common law in many countries today, and the more efficient model of rule he created helped transform England into one of the most powerful and well-run kingdoms in Europe. Fittingly, he was married to the wealthiest, shrewdest, and most beautiful woman in 12th century Europe: Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204).

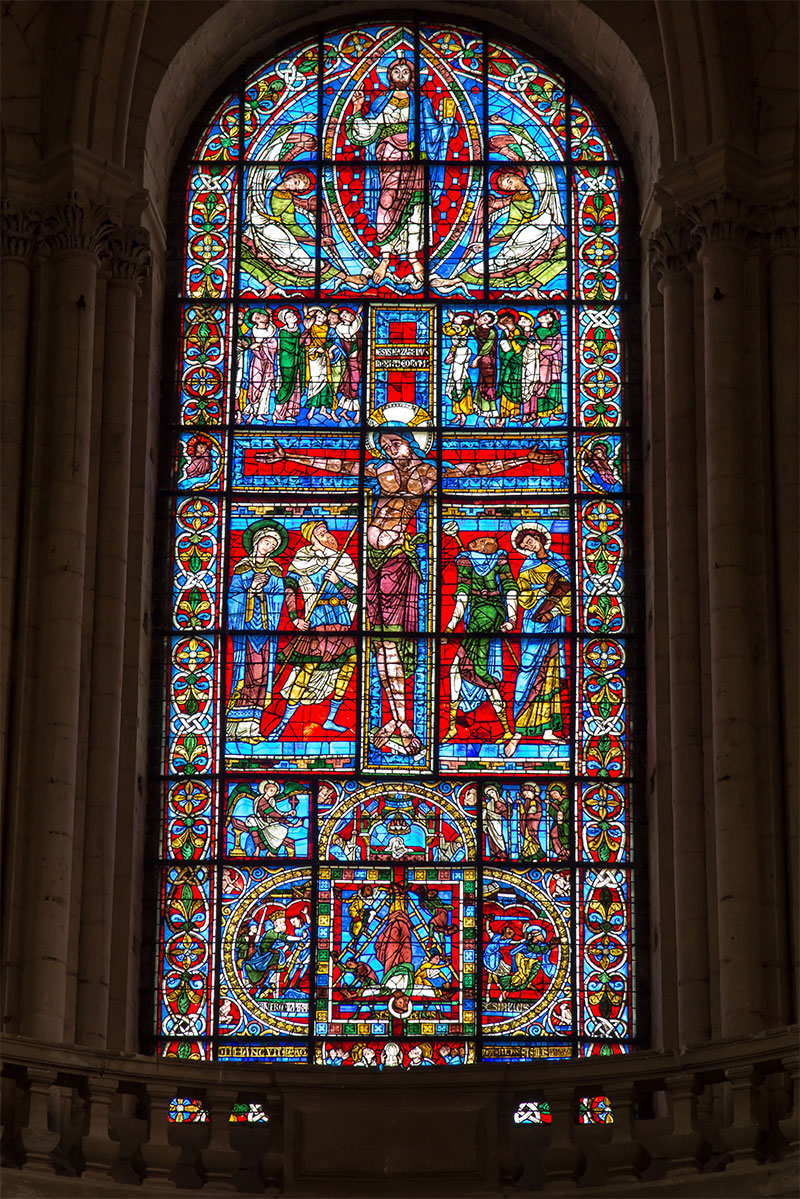

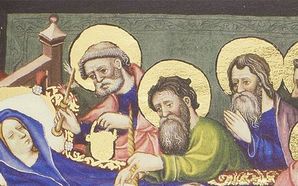

Henry and Eleanor patronized one of the oldest stained-glass windows in France, the East Window of Poitiers Cathedral, where they were married in 1152 – only 8 weeks after the annulment of her marriage to King Louis VII of France. The cathedral was rebuilt in the new Gothic style a decade after their marriage, and the window shows the royal couple with their four sons presenting gifts to God – an image of piety and family solidarity.

However, Henry would have a tumultuous relationship with his wife and four sons, which sometimes broke out into open war, known as the Great Revolts, which were often instigated by King of France, who had been humiliated when Eleanor, his ex-wife, gave Henry four sons after giving him none. Two of Eleanor’s sons would become kings, the famous Crusader Richard the Lionheart and King John, infamous villain of the Robin Hood legend.

Becoming an English Dynasty

To the facsimile

King Richard I of England (1157–99) was a military genius but an otherwise inept ruler who did not speak English and did not even like England – he spent only about 6 months of his reign there and preferred sunny Aquitaine. While on Crusade, his brother John (1166–1216) lost nearly all their lands in France and Richard died while trying to reconquer them. John’s tyrannical rule and licentious behavior eventually stirred up the barons against him, resulting in the Magna Carta of 1215, the founding document of the modern British and American legal systems.

Driven out of France, the Plantagenets focused on securing their rule in England. Henry III (1207–72) rebuilt Westminster Abbey in a grand French style but dedicated it to the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor. His son King Edward I (1239–1307), called Longshanks for his unusual height, was a reformer of government and common law who established a permanent parliament. He also extended English control over Wales and earned the nickname “Hammer of the Scots” for his attempts to do likewise to Scotland.

To the facsimile

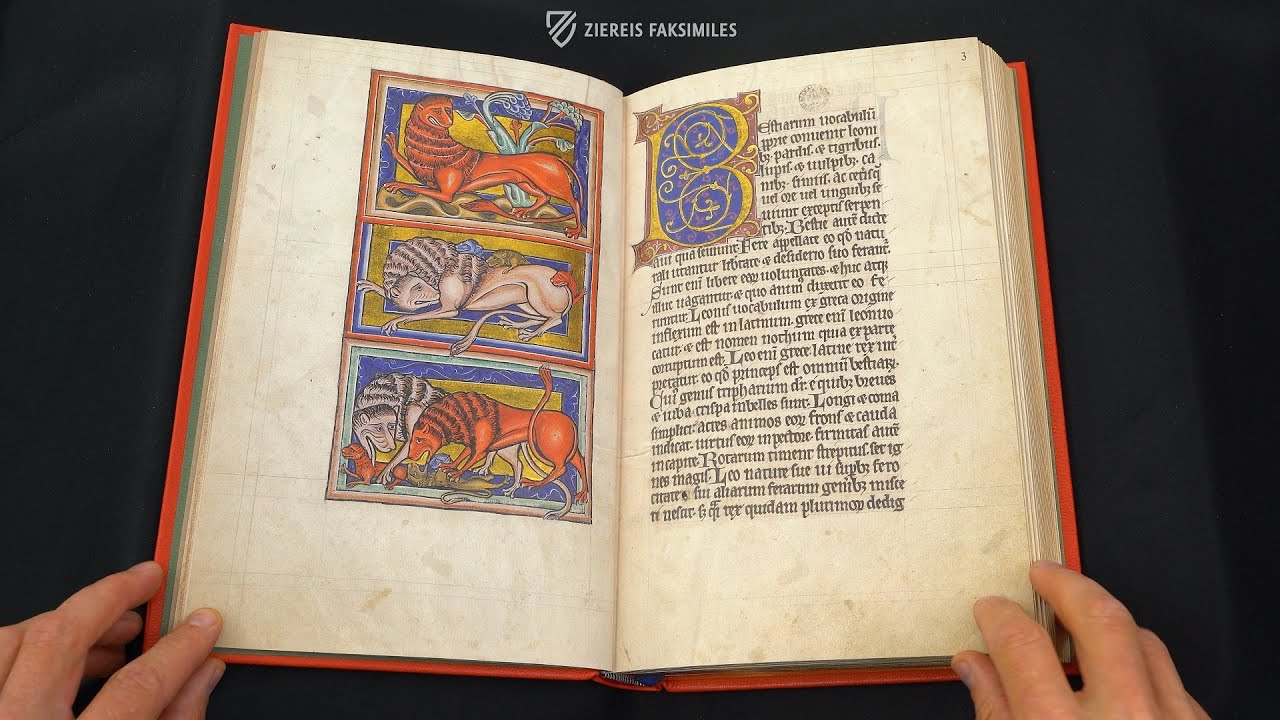

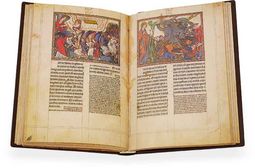

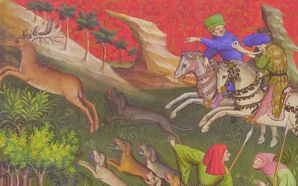

The wealth of Edward’s kingdom is reflected in the sophistication of English Gothic art, such as the miniatures found in the Oxford Apocalypse, which was commissioned by Edward I himself. Artists on both side of the Channel continued to produce fine works of during the 13th and 14th centuries. This includes some of the finest Psalters and Apocalypse manuscripts of the period as well as unique masterpieces like the Holkham Bible.

Chivalry and National Identity

The Hundred Year’s War (1337–1453), a series of wars spanning 116 years and five generations, began with a dynastic crisis: King Charles IV of France died without sons or brothers in 1328 and his sister Isabella de France put forth her son – King Edward III of England (1312–77) – as the heir. Edward III not only invaded France but also undertook the Plantagenets’ most ambitious building project yet: he transformed Windsor Castle into a palace at the center of his kingdom, a perfect setting for royal displays of chivalry that was partially funded by ransoms from victories at Crécy, Calais, and Poitiers.

This spirit of chivalry was most clearly articulated in his establishment of the Order of the Garter in 1348, which still exists today, complete with a splendid chapel for their use at Windsor. Edward thus increased the loyalty of the kingdom’s most elite soldiers while simultaneously interlinking English and Plantagenet identities. Edward III also adopted St. George as patron saint of England – a warrior saint for a warrior king. Aside from creating a Plantagenet Camelot, in 1367 Edward became the first king to open a session of parliament in the English language.

Last Flashes of Greatness

To the facsimile

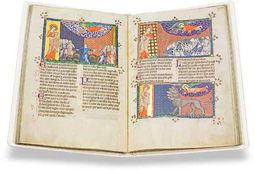

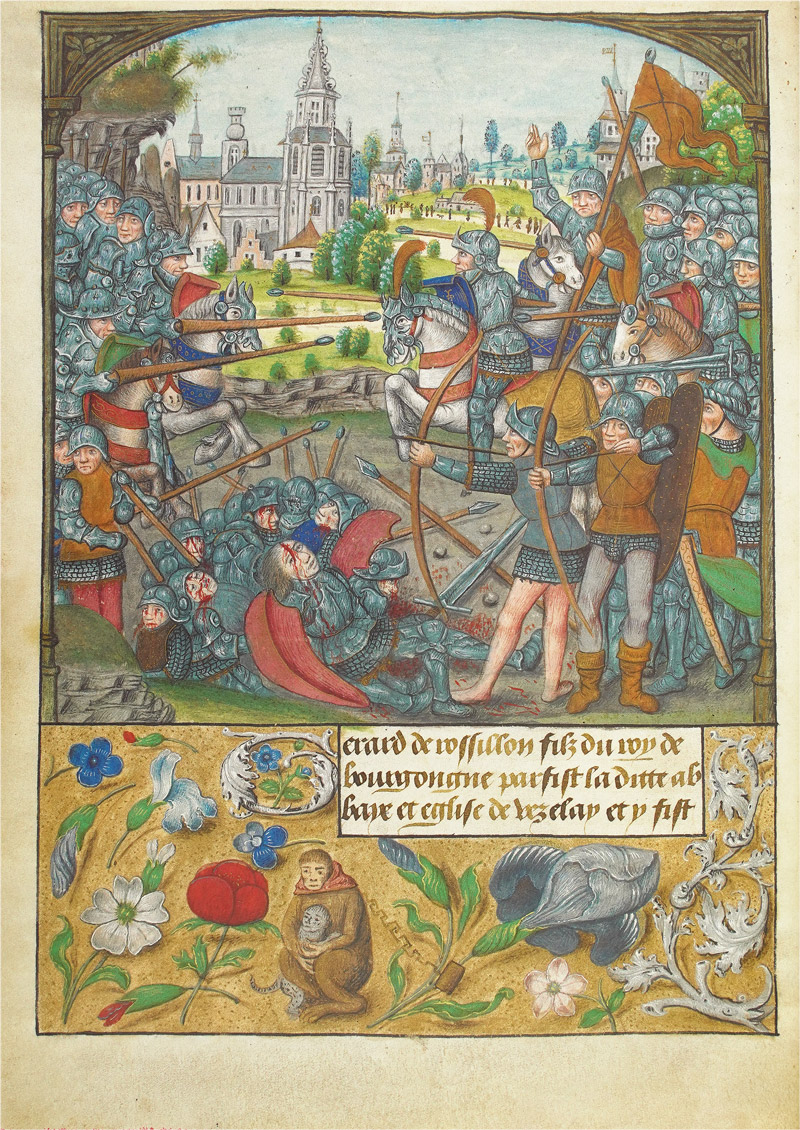

Although Henry V (1386–1422) achieved immortality at his heroic victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the Plantagenet dream of empire ended in disappointment and division. The Plantagenets were soon embroiled in a series of civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485) that would eventually bring an end to the dynasty and result in the ascension of Henry Tudor (1457–1509) to the throne as King Henry VII. Nevertheless, they provided one last flourishing of art and culture in medieval England.

To the facsimile

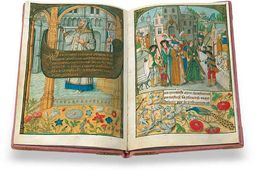

The court of Edward IV (1442–83) was one of the most splendid in Europe, partially thanks to the construction of a magnificent new royal banqueting hall at Elton Palace, and the King commissioned many illuminated manuscripts from the best masters in Bruges. In fact, one became known as the Master of Edward IV, evidence of whose skillful hand can be found in at least forty-five manuscripts ranging in date from 1470 to 1500 and including both religious and secular works.