Beatus Manuscripts: Captivating Book Art on the Famous Apocalypse Commentary by Beatus of Liébana

Beatus manuscripts, illuminated codices presenting the Commentary on the Apocalypse by the 8th century Spanish monk and theologian Saint Beatus of Liébana are among the most fascinating codices produced during the Middle Ages. They are considered to be a genre unto themselves within the larger corpus of splendid medieval manuscripts of the Apocalypse, as the Book of Revelation was more commonly referred to during the Middle Ages.

The commentary by Beatus has survived to the present in 27 manuscripts, with new specimens being discovered in recent years. They were primarily produced in Northern Spain and are of special importance for Spanish art history, although Beatus manuscripts were also produced in France and Italy. The fantastic imagery often appears convoluted to modern people, but an eye attuned to the aesthetics and symbolism of the Middle Ages can easily decipher the illumination of these significant works of art.

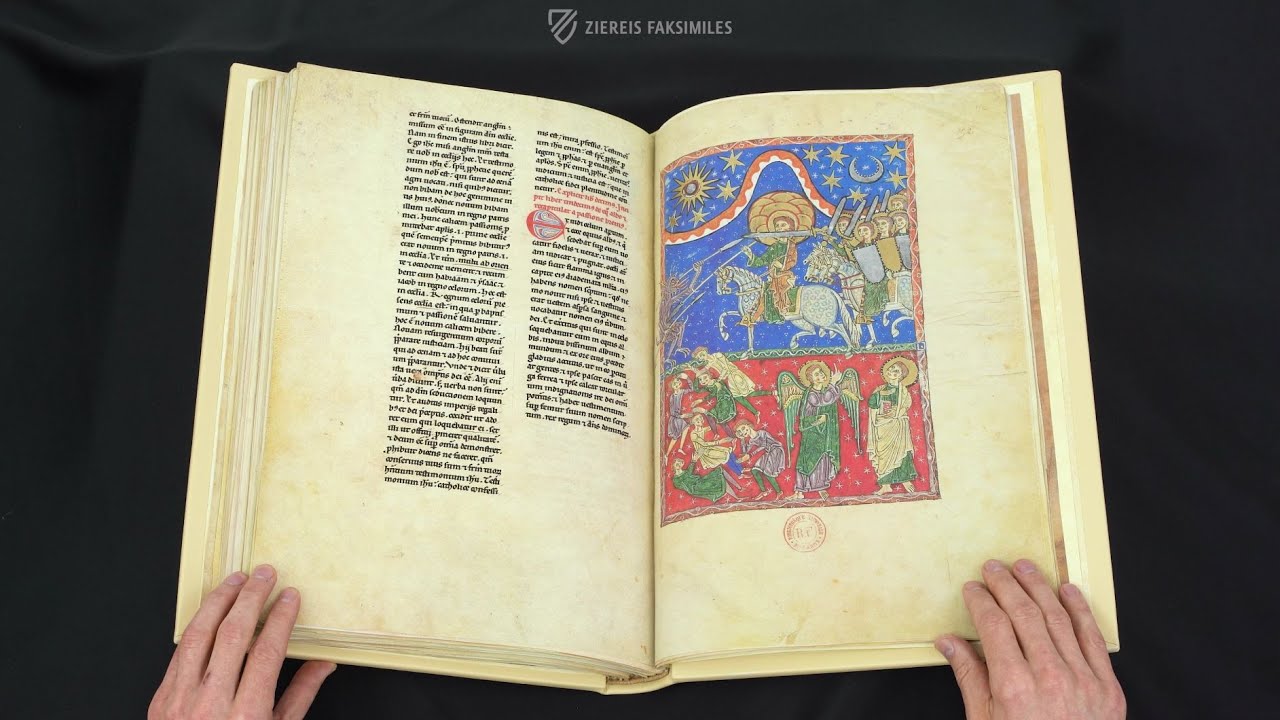

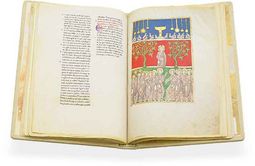

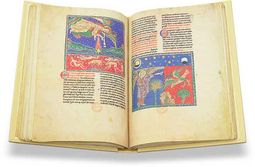

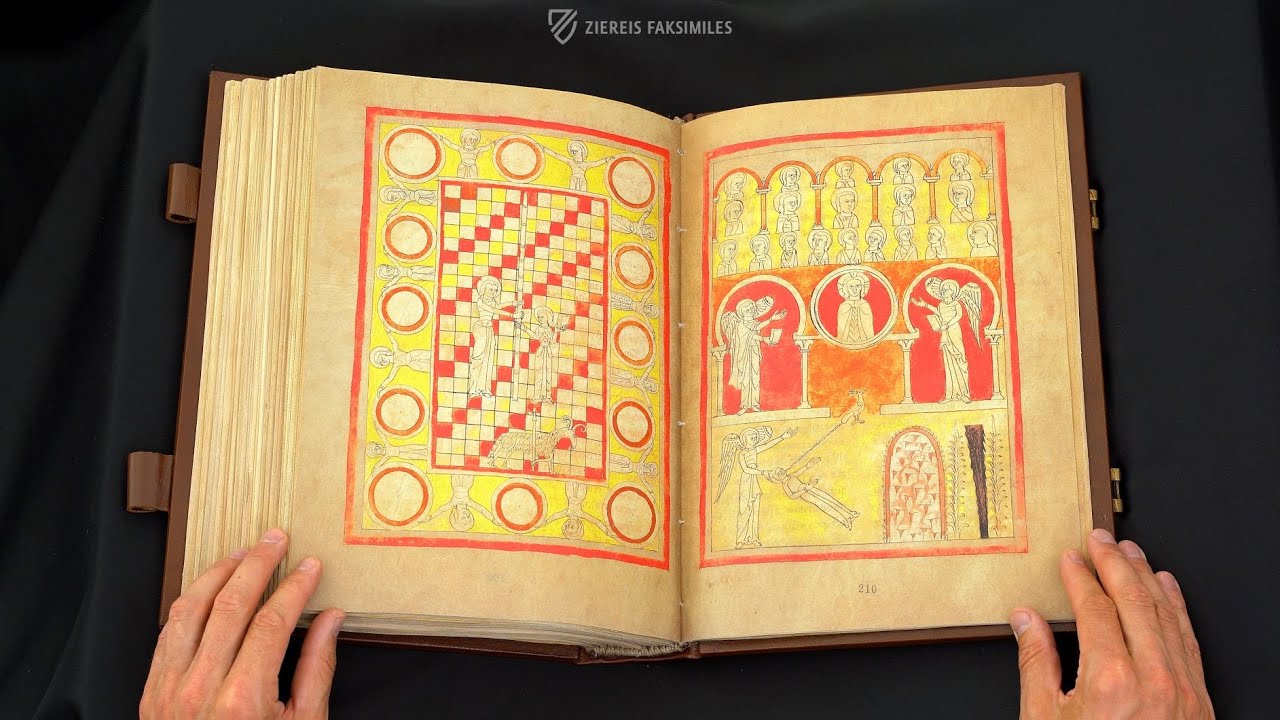

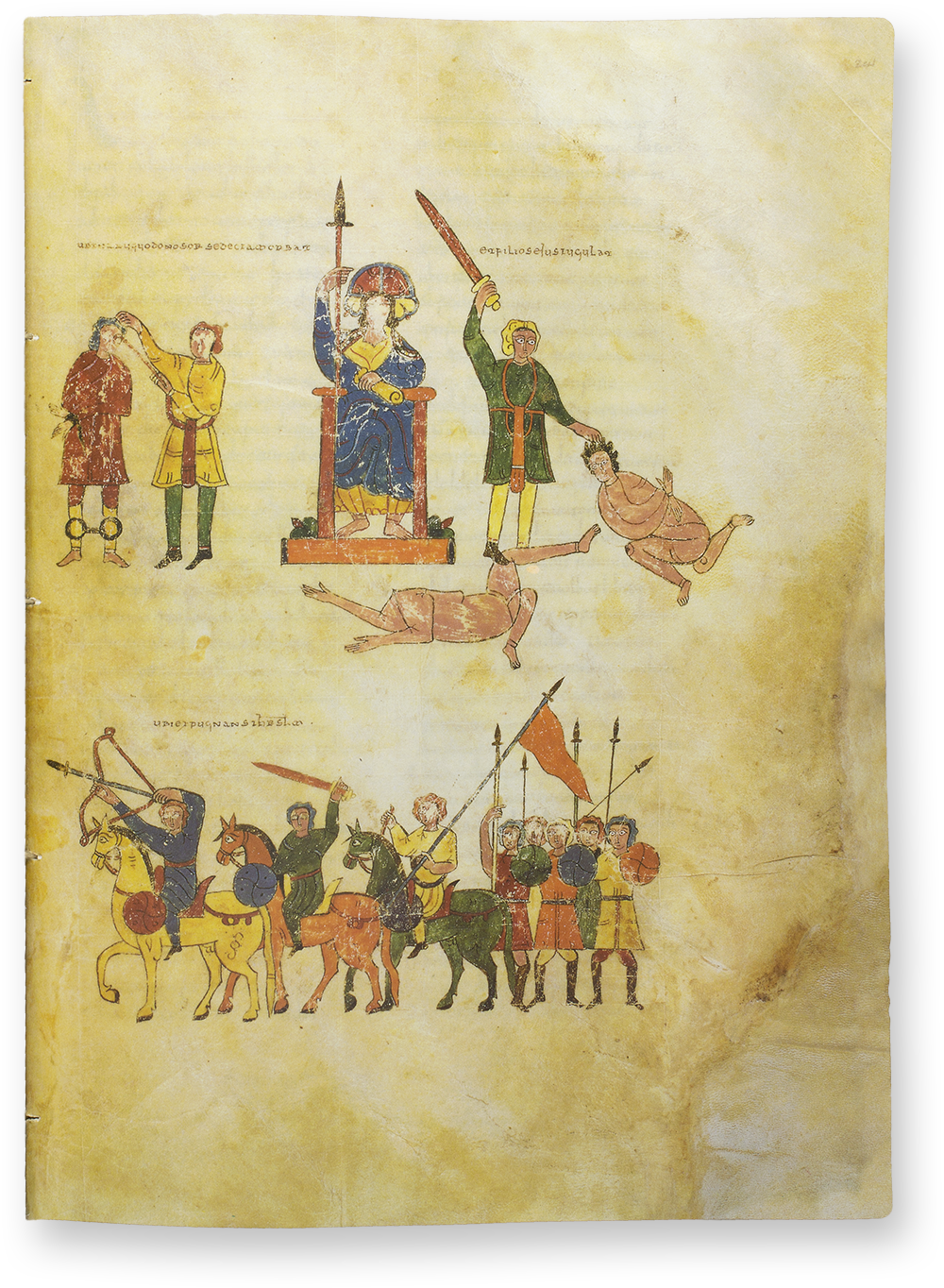

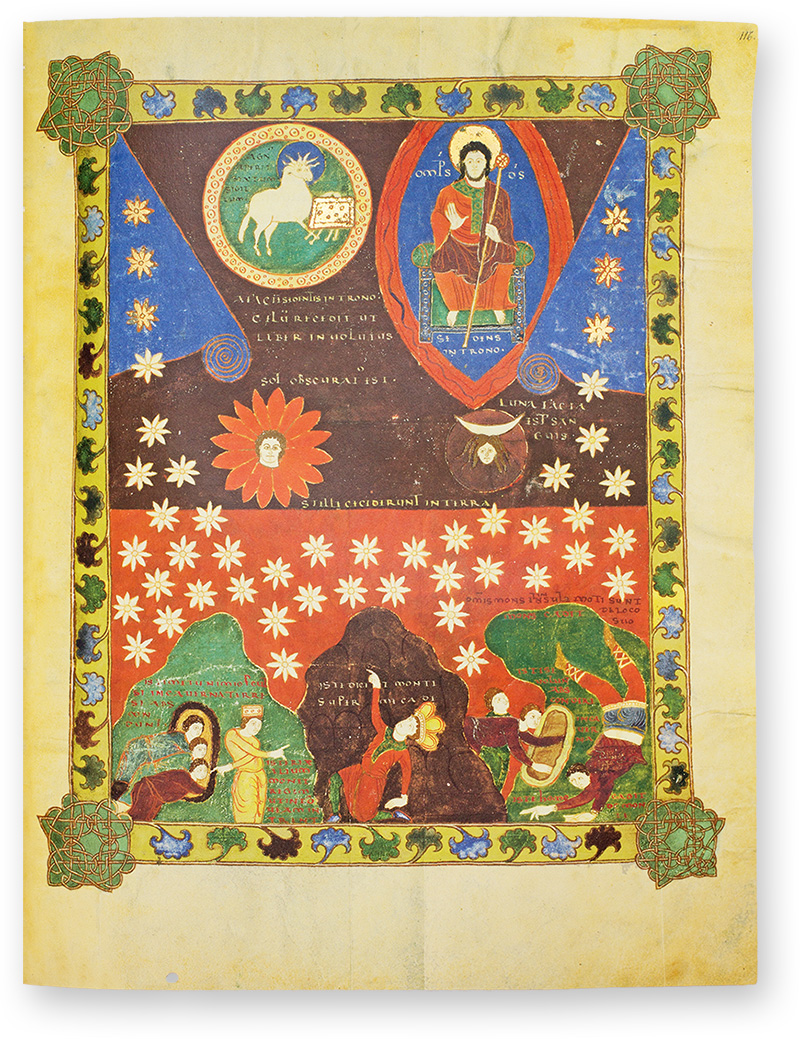

Demonstration of a Sample Page

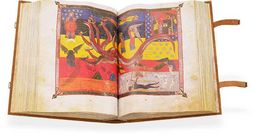

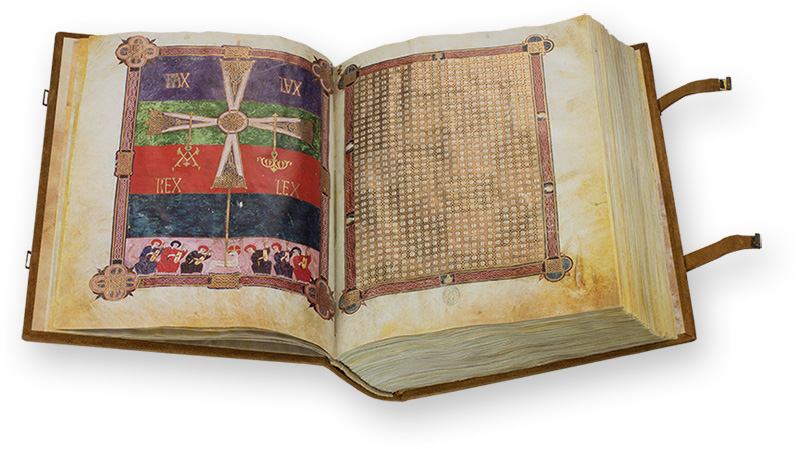

Codex San Miguel de Escalada (Morgan Beatus)

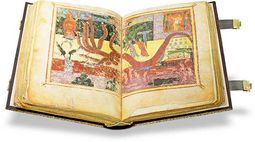

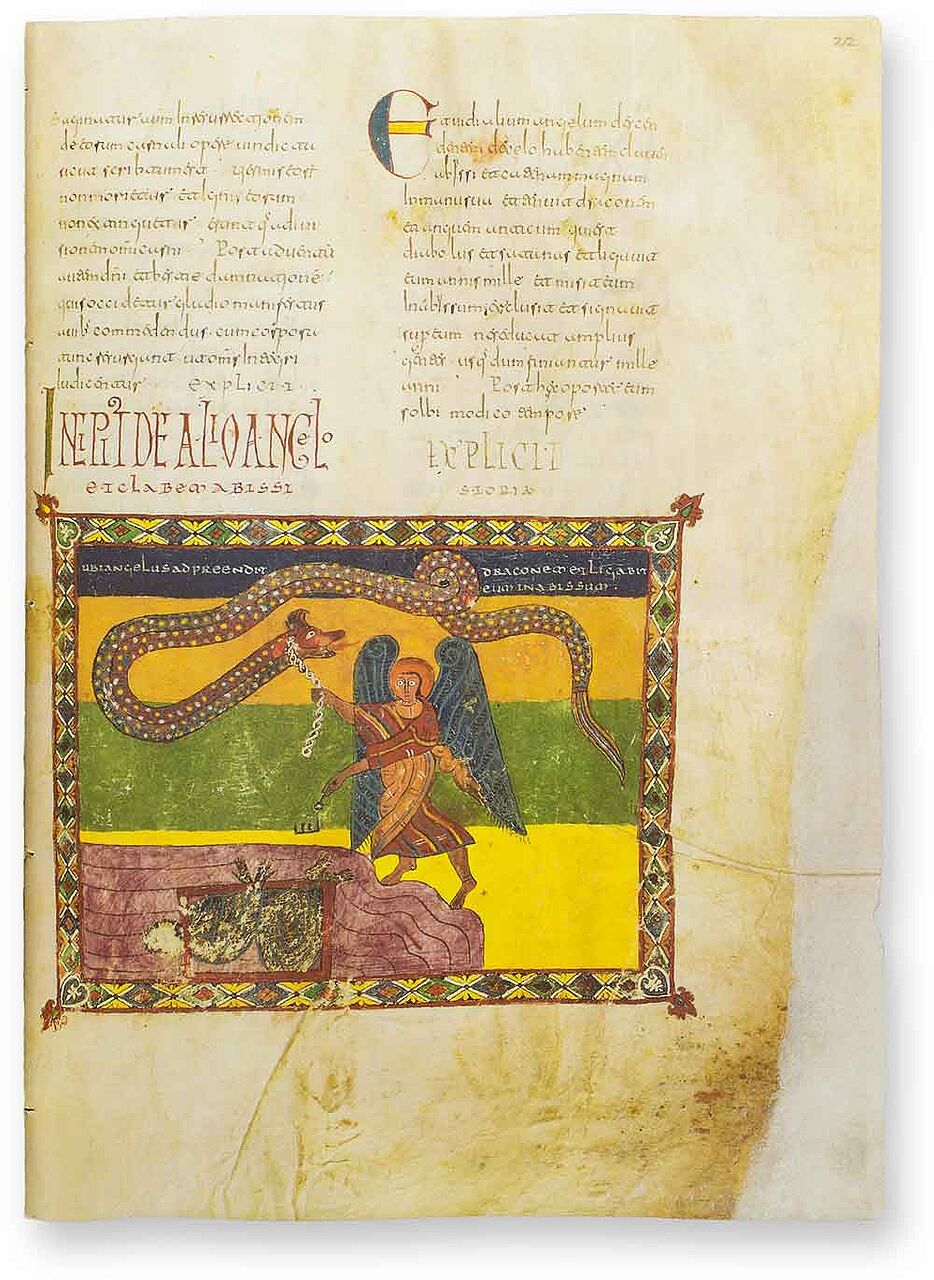

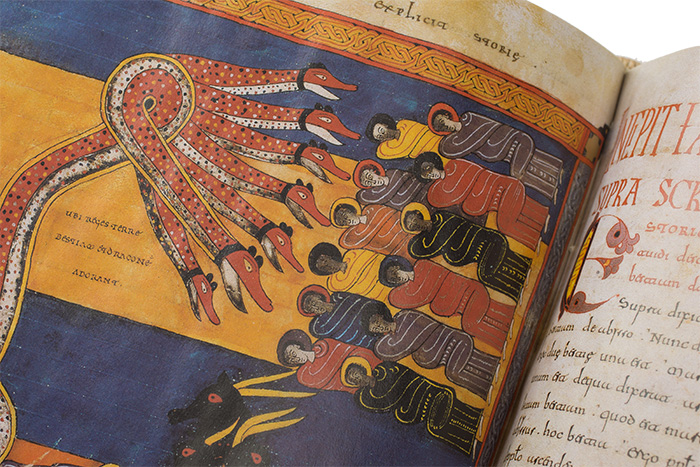

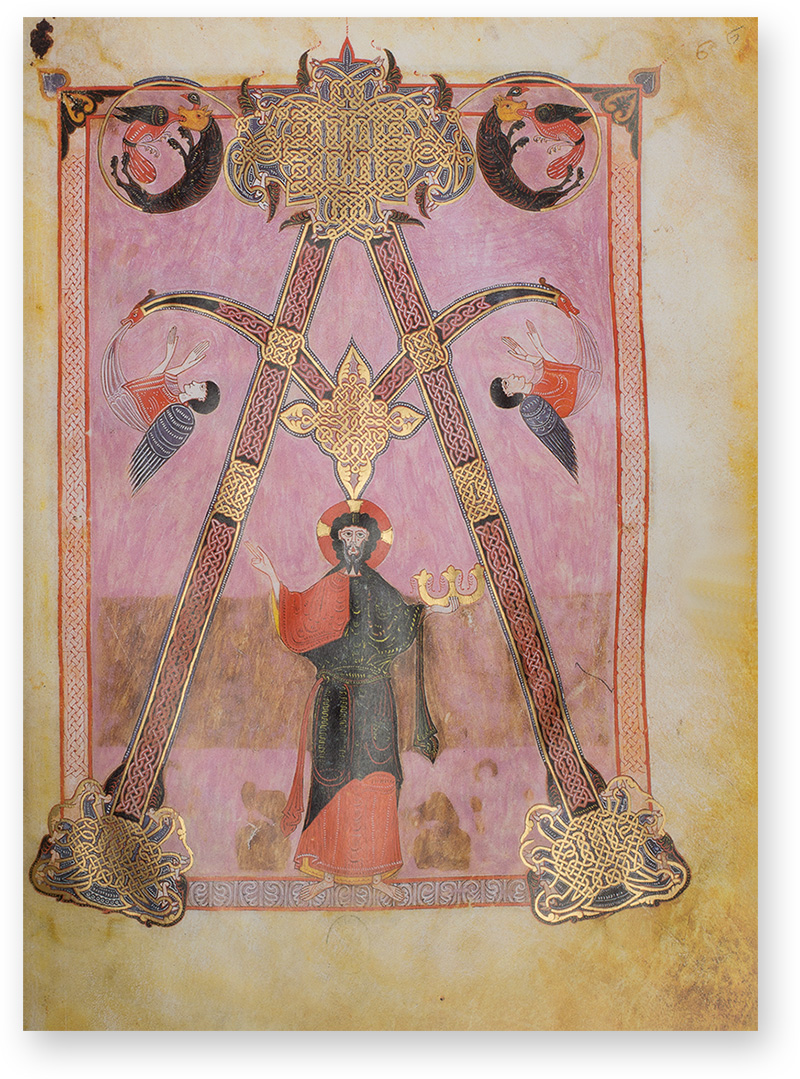

Satan Bound for 1,000 Years

“Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven, holding the key of the abyss and a great chain in his hand. He laid hold of the dragon, that serpent of old, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years.” (Rev. 20:1-2)

Satan being thrown into the Abyss for 1,000 years is one of the most dramatic events in the Book of Revelation, and is depicted here in a manuscript exemplary of both the Beatus tradition and Mozarabic art. The selection of colors had symbolic significance for a medieval audience that is lost on modern people, e.g. multicolored backgrounds representing Heaven, Earth, and Hell. With unblinking Byzantine-style eyes, the angel solemnly leads the serpent to his prison with a chain rendered in silver.

The Legacy of Beatus of Liébana

Born in the Cantabrian Mountains of the Kingdom of Asturias ca. 730, Saint Beatus of Liébana (d. ca. 800) was one of the most important theologians of the Early Middle Ages. He rose from humble origins to become a royal confessor to Queen Adosinda of Asturia and taught other great minds like Alcuin of York and Etherius of Osma.

He has been immortalized by the popularity of his Commentary on the Apocalypse, written in 776 and revised in 784 and 786, which was a popular subject for illuminated codices known as the Beatus Manuscripts created between the 10th and 16th centuries, of which 27 survive to the present, some of which have only been discovered in the last couple of decades.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

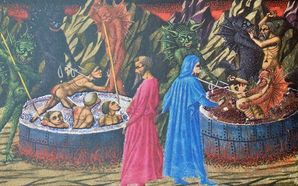

Beatus lived in the immediate aftermath of the Moorish conquest of Gothic Spain, and as such, themes of resistance and resilience are replete throughout the text, which itself came to be seen as a symbol of Christian resistance to the Muslim invasions of the Early Middle Ages. As such, the Beast no longer represented the Roman Empire but the Muslim Caliphate – Rome was replaced by Córdoba.

Ironically, Muslims are rarely mentioned directly and when so it is usually within the context of Christian heresy. This view of Muslims as Christian heretics rather than a completely different religion was also prevalent among contemporary Byzantine clerics and offers a reminder of their common theological origins. Therefore, the Beatus commentary also offers a window into early impressions of Islam.

Muslims were considered Christian heretics

To the facsimile

The Beatus Commentary

To the facsimile

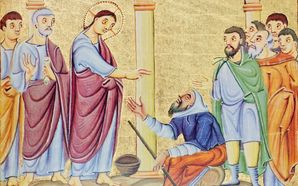

The commentary written by Saint Beatus is not particularly original, but is extremely scholarly and referential, an indication of the learnedness of the Spanish monk. The creativity of his writing is based in his wide-ranging source material and draws on practically every book of the Bible in addition to a multitude of sources written by various church fathers and theologians.

Beatus' commentary is based on various sources, from biblical texts to the Church Fathers

To the facsimile

Many have criticized the inability of Beatus to satisfactorily decode the convoluted narrative of John’s vision of the Apocalypse, pointing out that his commentary is replete with contradictions. Others have argued that this is a modern bias and that the medieval reader, living in a chaotic, quasi-apocalyptic world full of contradictions, would have found parallels to their own life in Beatus’ writings.

To the facsimile

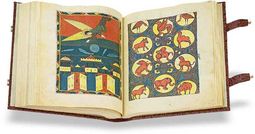

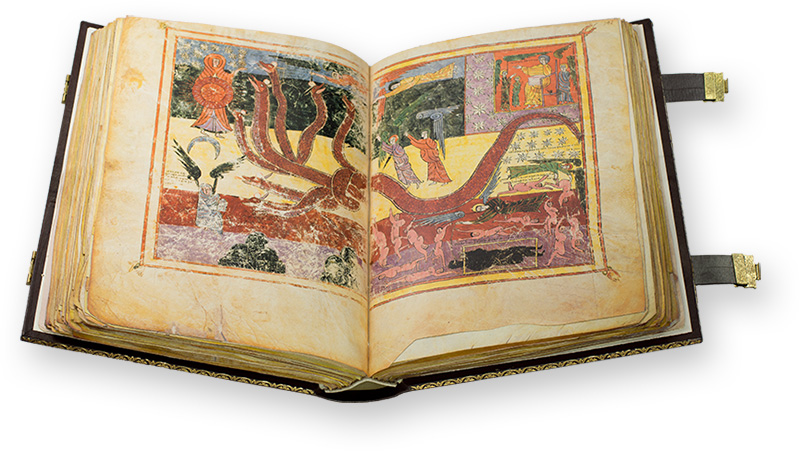

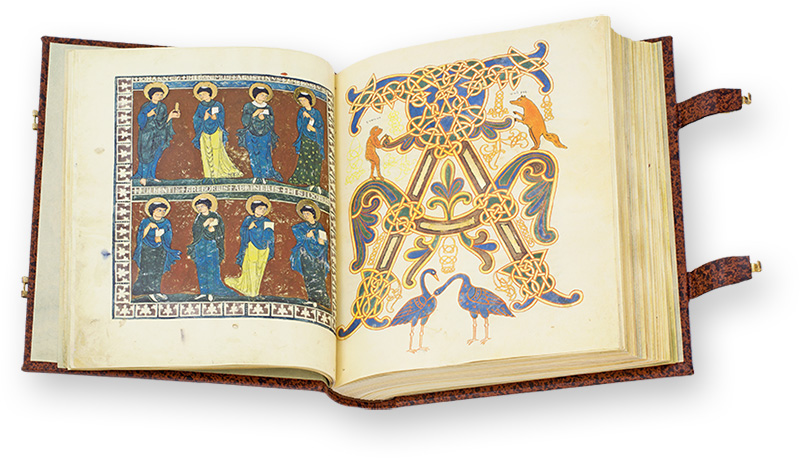

It is as a contemporary witness that Beatus is perhaps most valuable to cultural historians, e.g. the work is filled with homey similes reflecting the time and place he lived in. His outlook seems to be one of hope and love, in spite of the perilous nature of life in early medieval Spain, while still maintaining an attitude of realism toward church politics and the human condition. The artistic programs accompanying this text are typically dominated by shades of red and yellow, contrasted with darker, more ominous colors.

Artistic Evolution

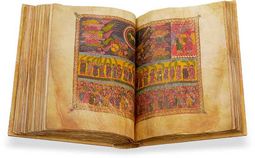

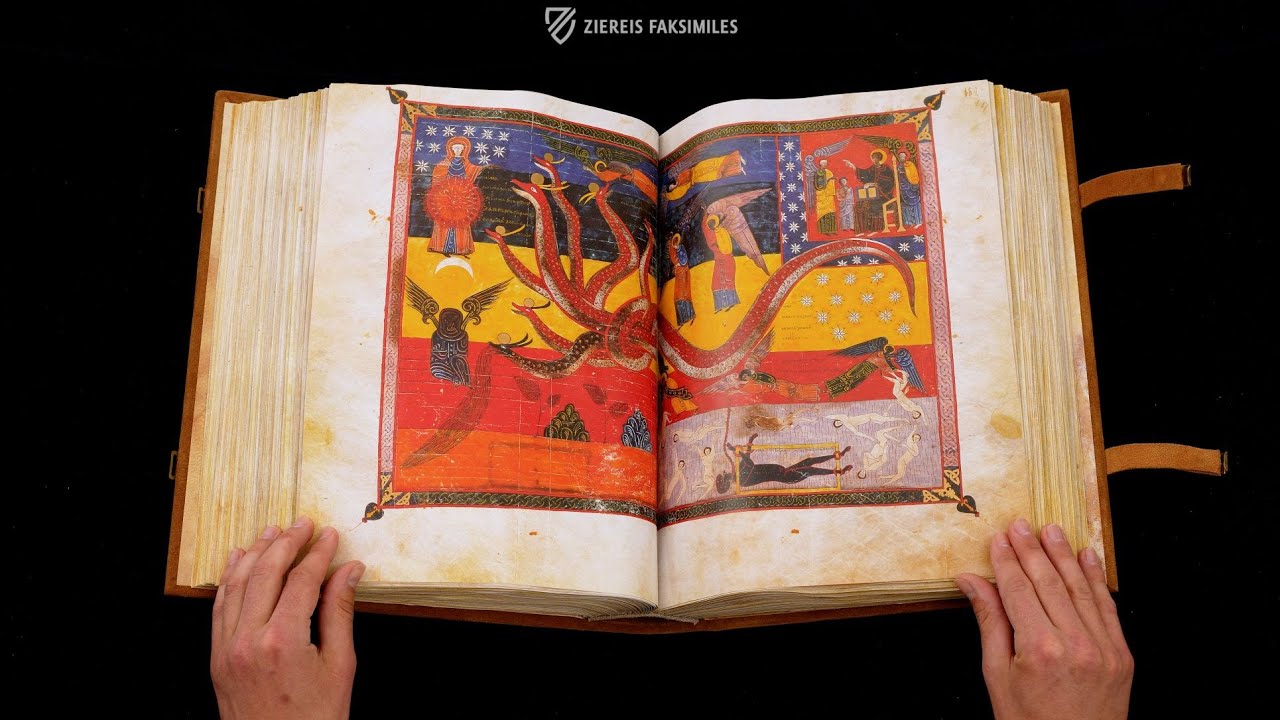

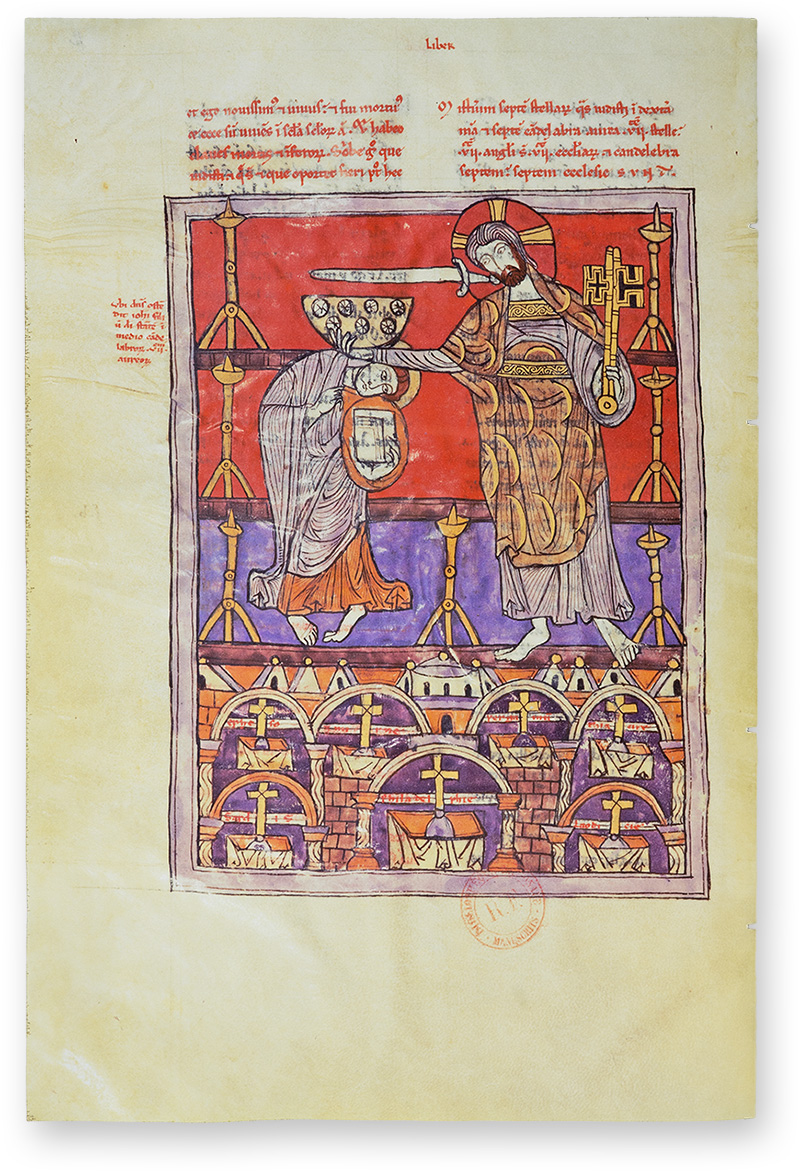

Although the 8th century original has not survived, there are early specimens belonging to “Branch I” of the corpus of Beatus manuscripts that reflect the style and character of the original. These are considered to be among the most important specimens of Mozarabic art and include the so-called Escorial Codex and the two-volume San Miguel de Escalada Codex.

To the facsimile

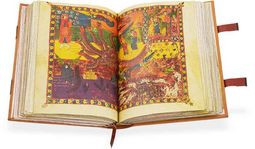

As the Christian kingdoms of Spain began to push back against the Moors in the 10th century, they simultaneously enjoyed greater prosperity, an ascendant culture, and artistic influences from other parts of Europe that fundamentally changed the style of Beatus illumination. The ongoing conflict with the Moors continued to be a common artistic theme.

Over time, the codices became larger and more opulent

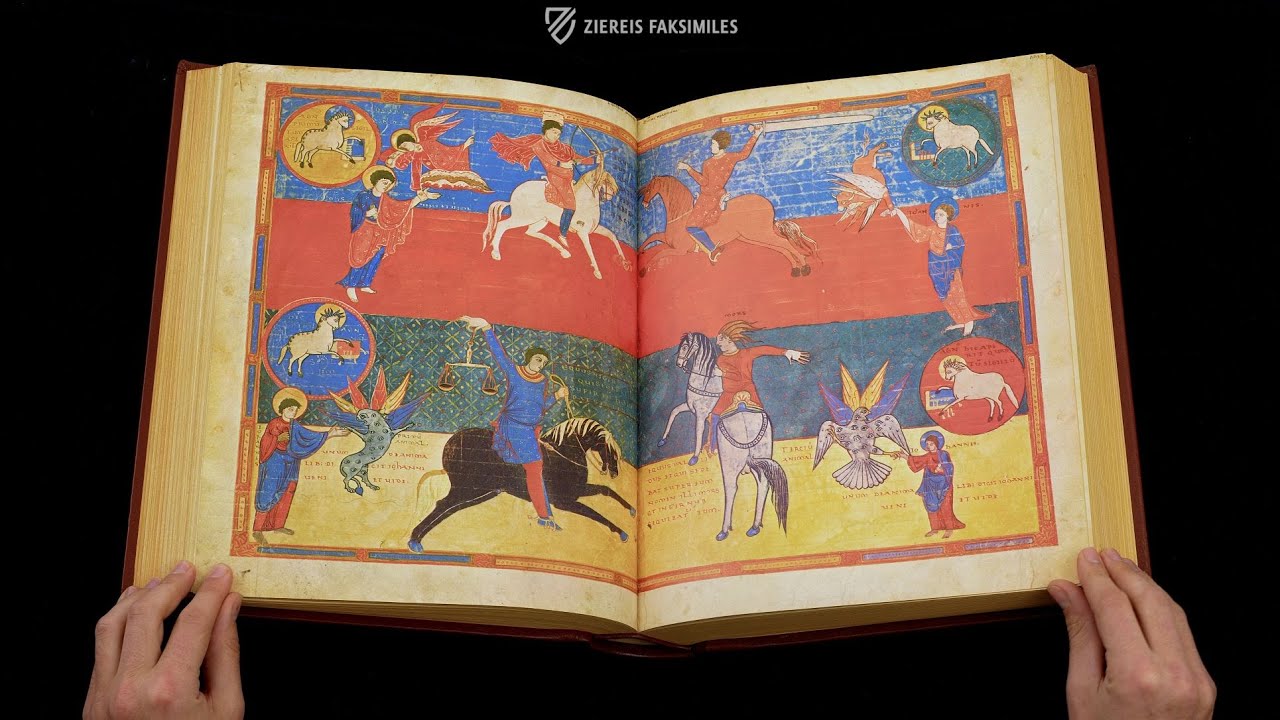

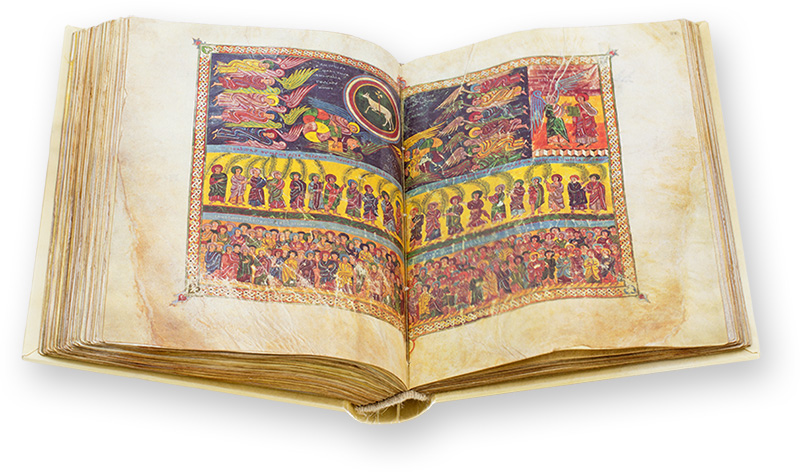

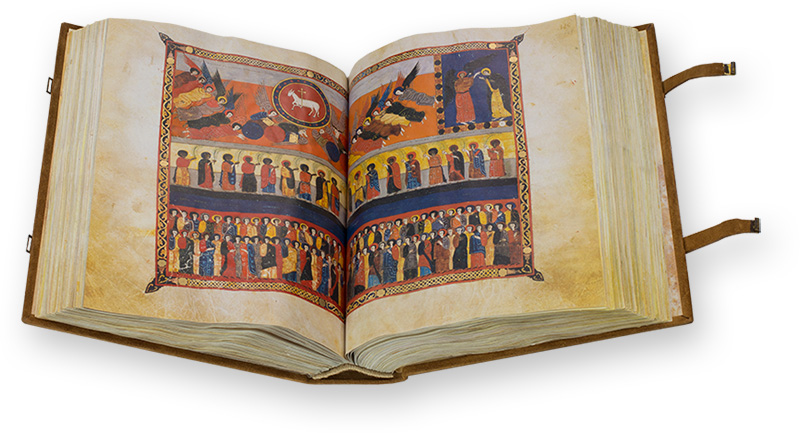

Codices became larger and the artistic adornment of these “Branch II” manuscripts became more expansive (now including double-page miniatures), richer, and more numerous. Commissioned by King Ferdinand I, the Facundus Codex is considered to be a milestone of Spanish illumination.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

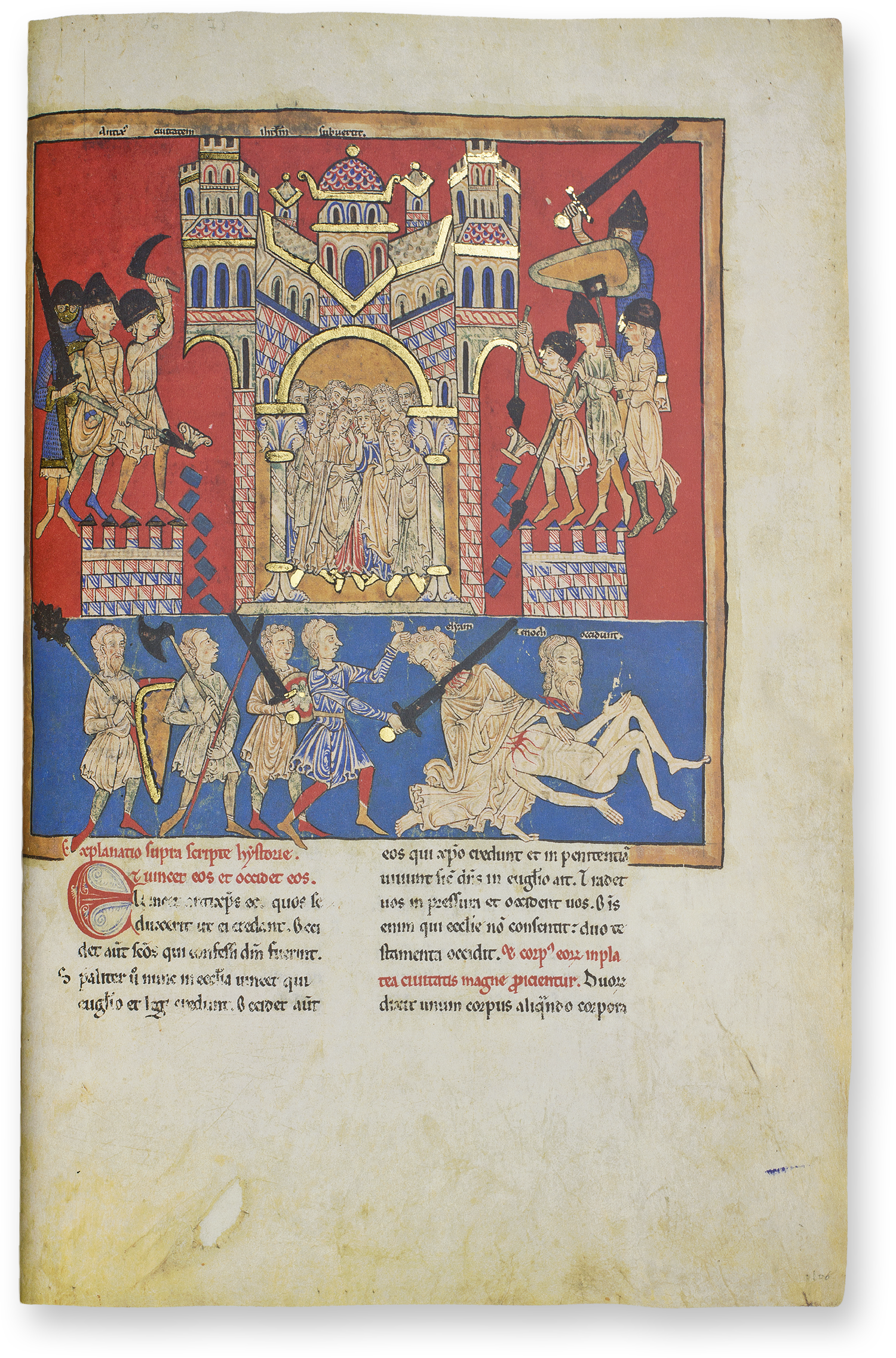

This second generation of Beatus manuscripts includes the most beautiful and influential of the Spanish manuscripts and the ones that would inspire Beatus manuscripts in France and Italy during the High Middle Ages, representing the last generation artistically. The Saint-Sever Codex is considered to be a highlight of 11th century French illumination. Among the features that make Beatus manuscripts significant for the history of illumination is the fact that they often included a world map – a rare insight into the geography of the post-Roman world!

To the facsimile

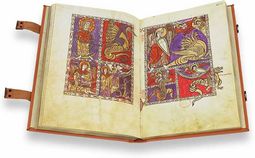

Deciphering the Illumination

To the facsimile

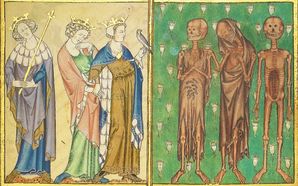

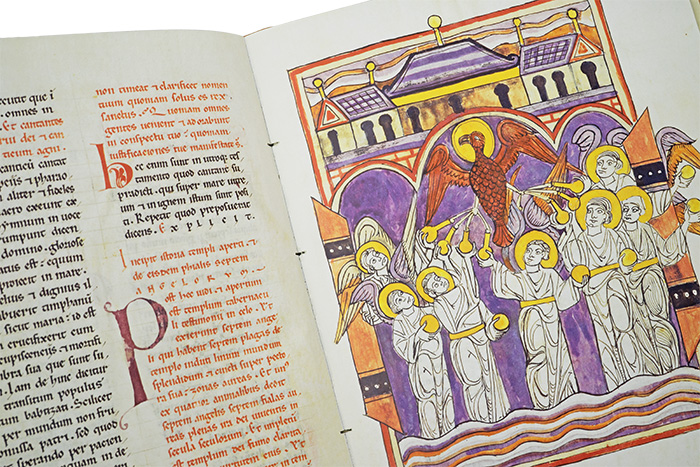

The Book of Revelation is among the most enigmatic texts found in the Bible and according to some traditions is part of neither Testament but belongs more properly among the Apocrypha. Properly depicting the events of the text yields some strange and mysterious illustrations. This imagery was meant to support the text, but also functioned independently of it in order to inspire the reader to contemplation.

To the facsimile

The selection of color was critical in a manuscript because of the way they were interpreted by medieval Europeans. Bright hues and stark contrasts that are gaudy by modern tastes would have been understood by a medieval audience who could recognize the symbolic significance of various colors, e.g. colors could denote good or evil.

To the facsimile

For example, the miniatures of the San Miguel de Escalada Codex are divided into three parallel strips by colors, allowing events from different points in time to be represented simultaneously. These miniatures do not follow a chronological order from left to right, top to bottom, as is typical. Instead, they point to the space in which the action is occurring, which the medieval beholder would immediately recognize as Heaven, Earth, and Hell.

This lack of focus on chronological accuracy points to the problems of analyzing a medieval manuscript as a modern person – we are not the intended audience of these works. Therefore, anyone attempting to decipher these medieval masterpieces must do their best to rid themselves of the prejudices of presentism and open their mind to new modes of thought.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile