Apocalypses

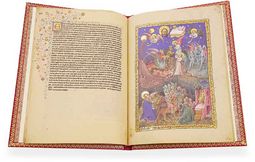

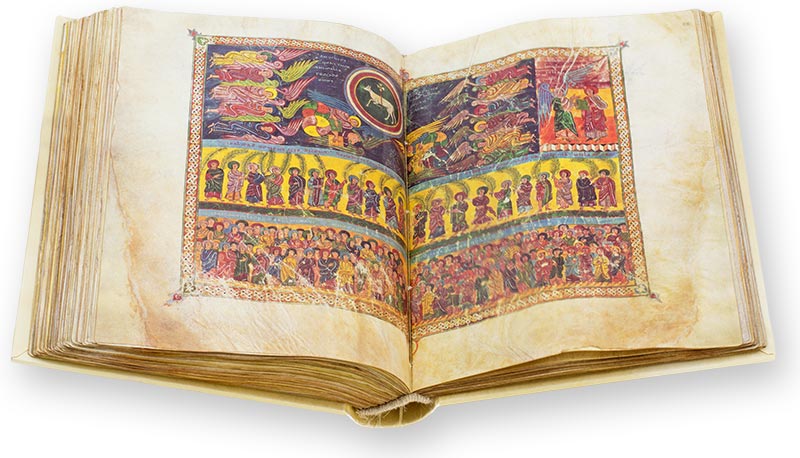

The Apocalypse manuscripts of the Middle Ages are timeless classics among art lovers, just as they were treasured by the artists who created them. The Book of Revelation is indeed one of the most fascinating works in the Western cultural canon. Its cryptic imagery has always captivated theologians, historians, art historians, literary scholars, philosophers, and many more.

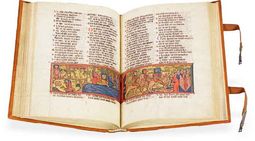

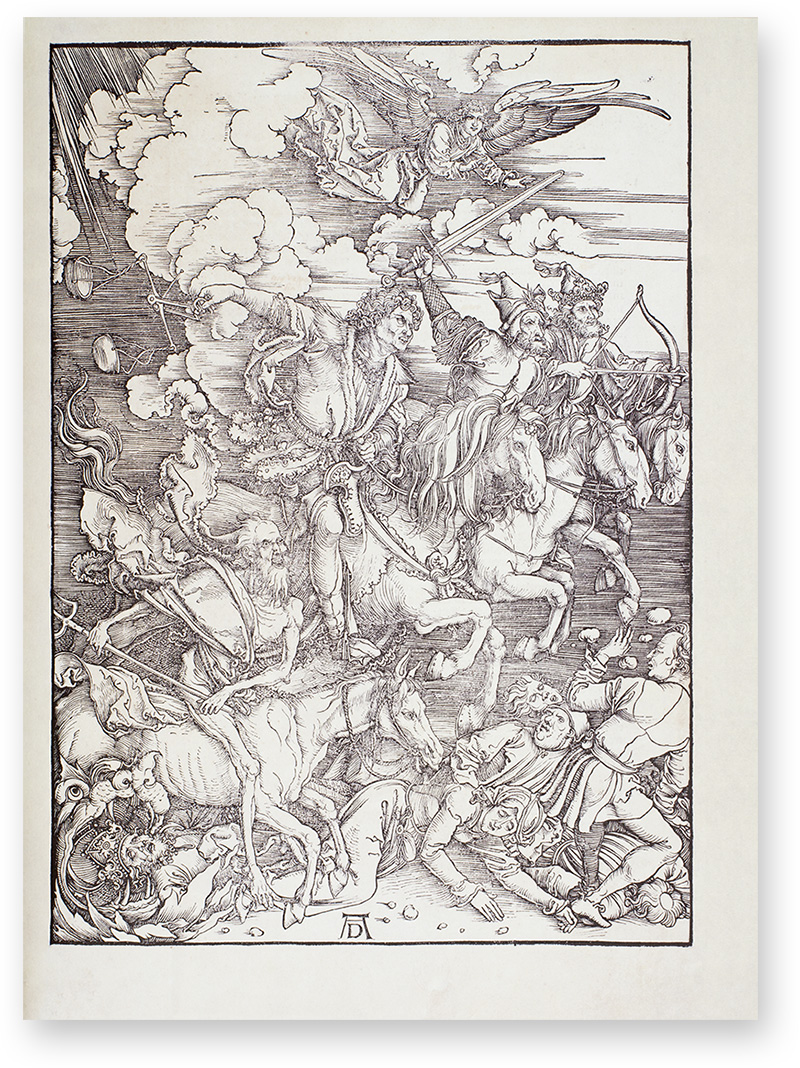

For medieval book artists and miniaturists, the visual implementation of the unusually terrifying narrative was a way to fully develop their creativity and artistic freedom by designing images that under other circumstances would have drawn accusations of blasphemy. The apocalypse is every artist's dream with its smorgasbord of fantastic beings, mysterious numerology, and fascinating symbolism. Both anonymous Carolingian masters and well-known artists such as Albrecht Dürer were captivated by the special charm of the text. Apocalypse manuscripts were produced from the 8th century up through the Renaissance and the beginning of the printing age. Almost all of the artistic styles and epochs of the European Middle Ages are represented thereby. In the 8th century, the Spanish monk Beatus von Liébana wrote a commentary on the Apocalypse that was extremely widespread and forms a separate sub-genre of the text tradition with 27 surviving manuscripts.

A juxtaposition of the different manuscripts and their miniature cycles is particularly instructive in the case of the Apocalypse. Since the images follow the same text and the program of the scenes depicted was relatively fixed, the differences between the various art-historical epochs, styles, and production sites can be recognized and tracked in a particularly clear manner. To this day, Apocalypse manuscripts are among the most valuable and sought-after artifacts of medieval illumination.

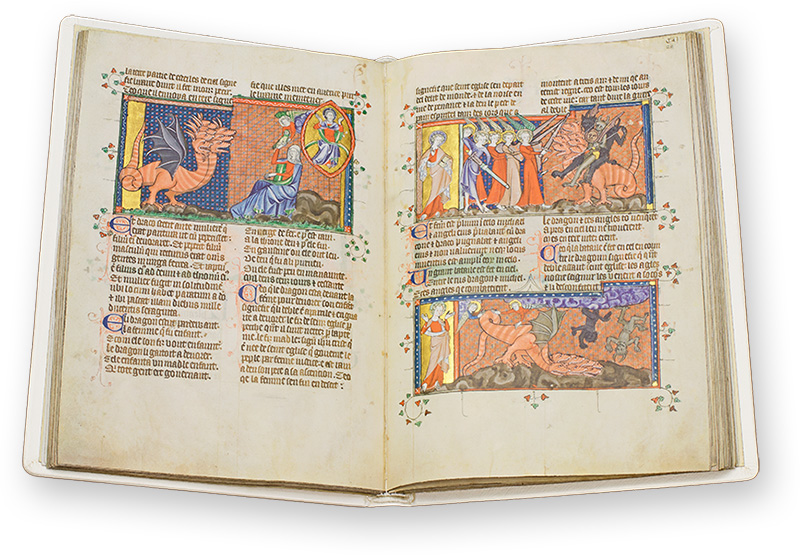

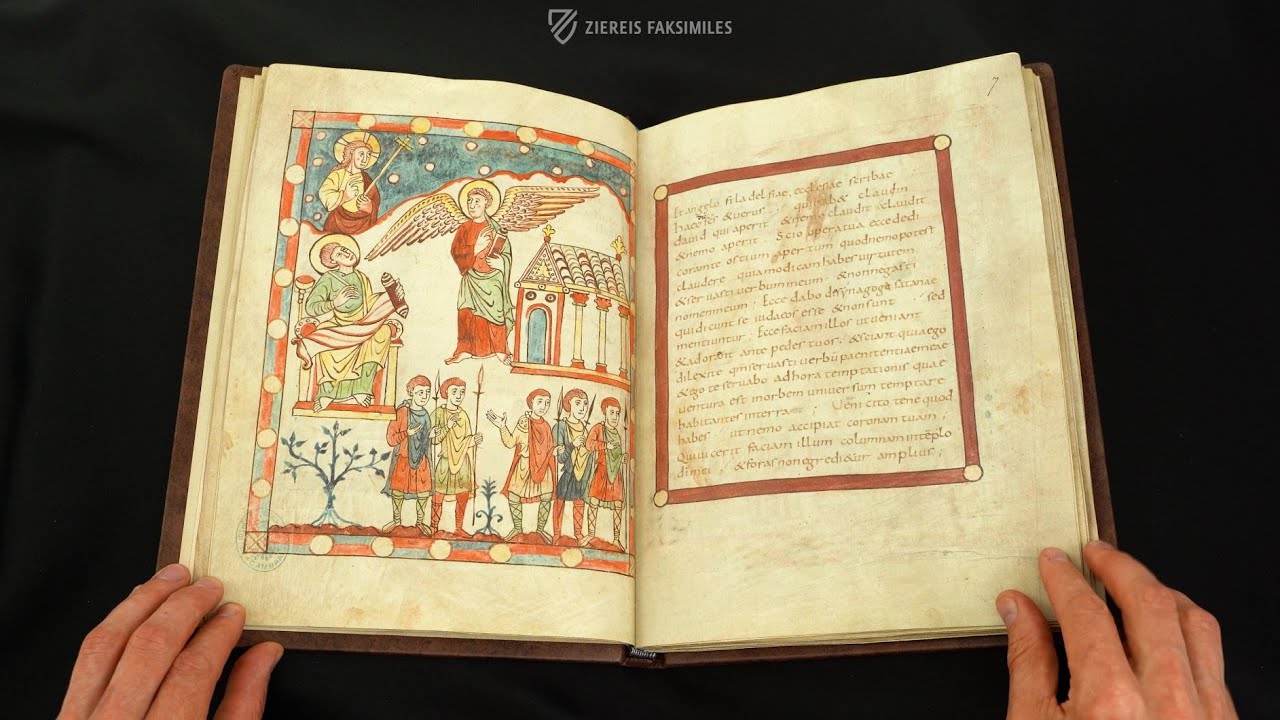

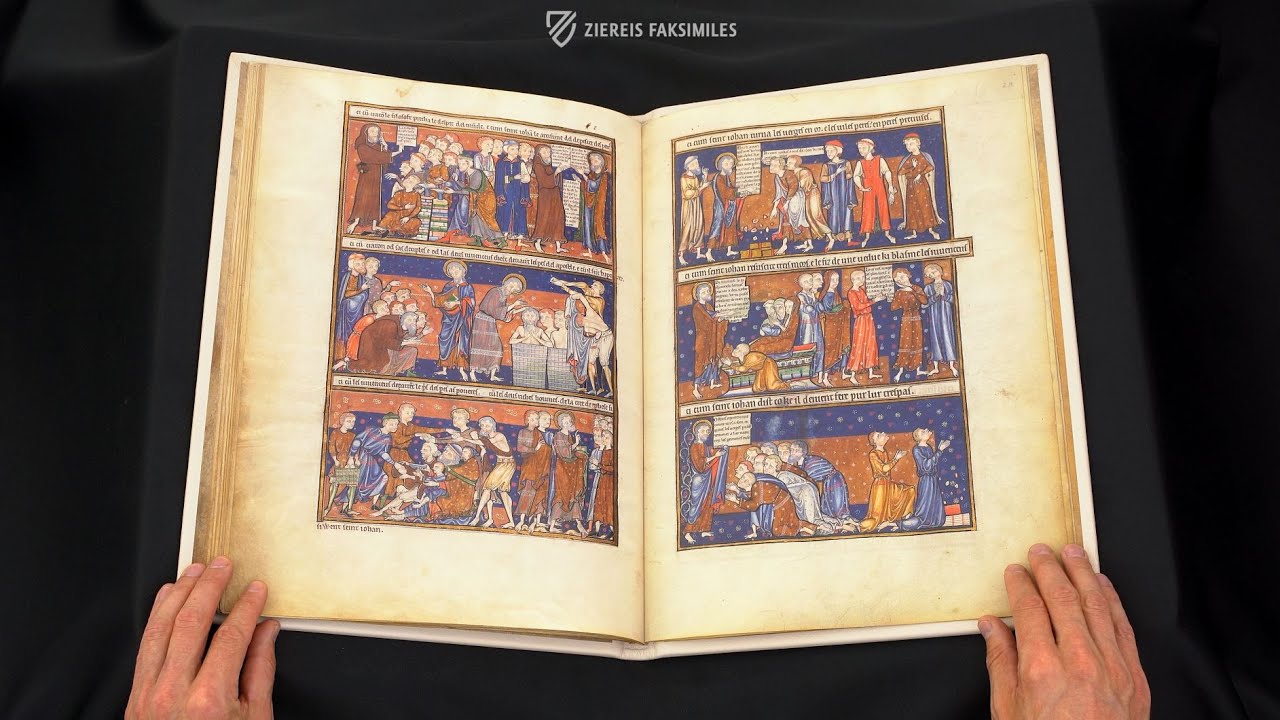

Demonstration of a Sample Page

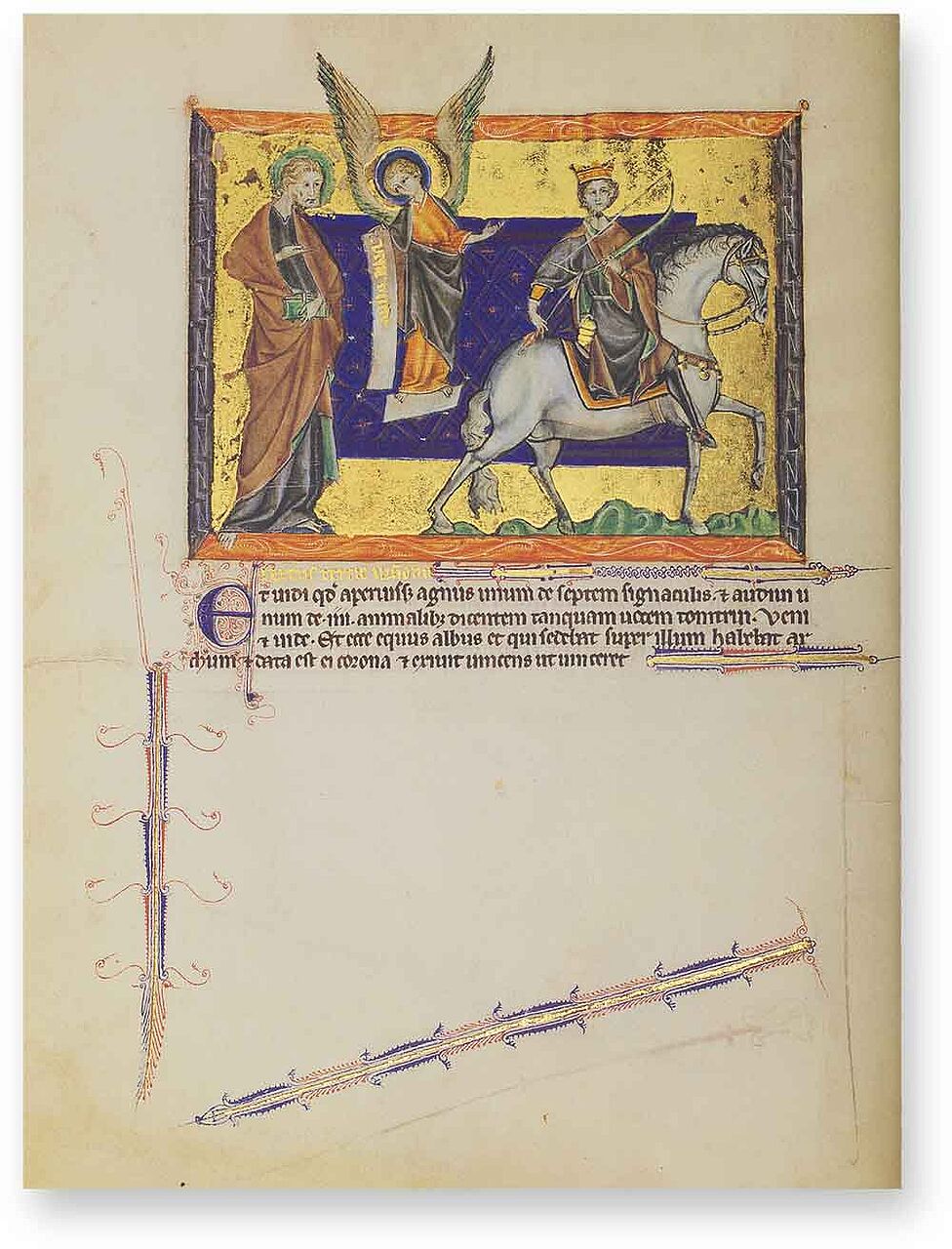

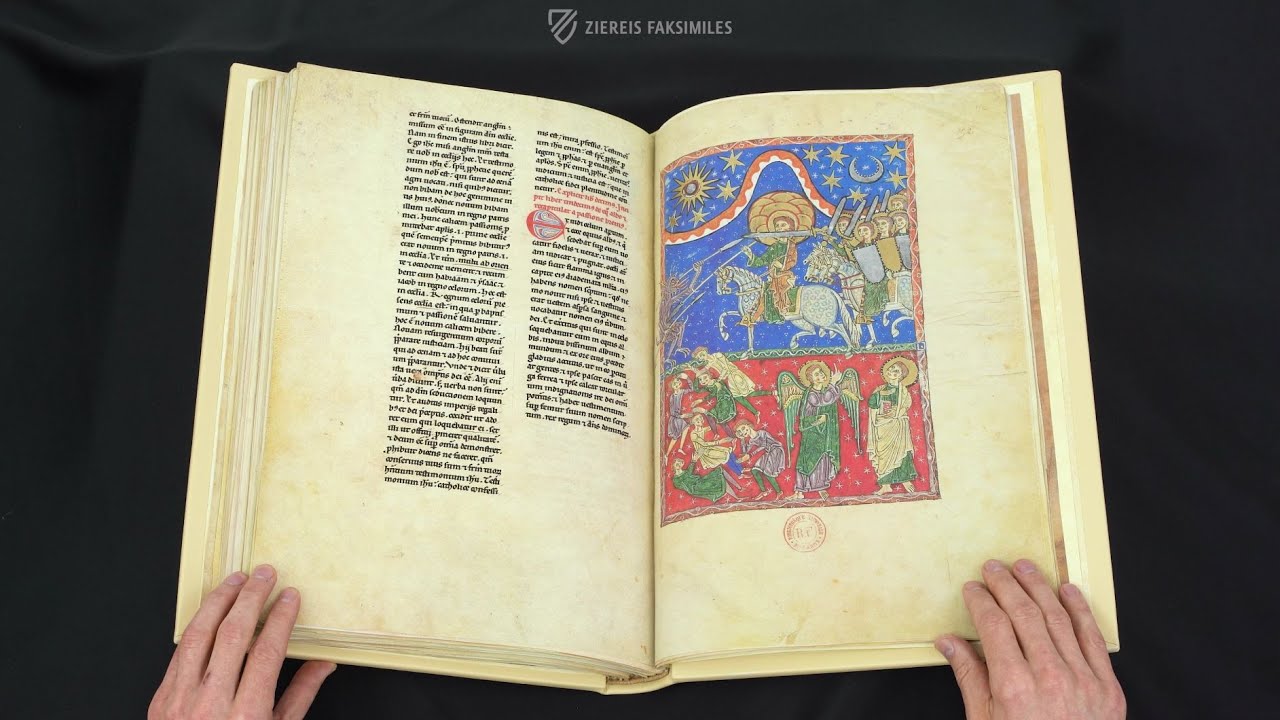

Gulbenkian Apokalypse

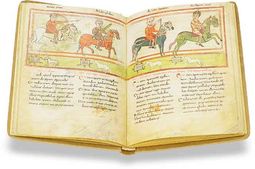

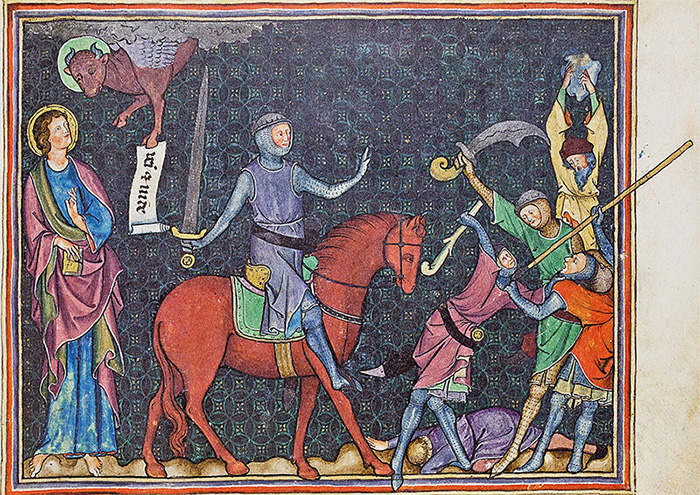

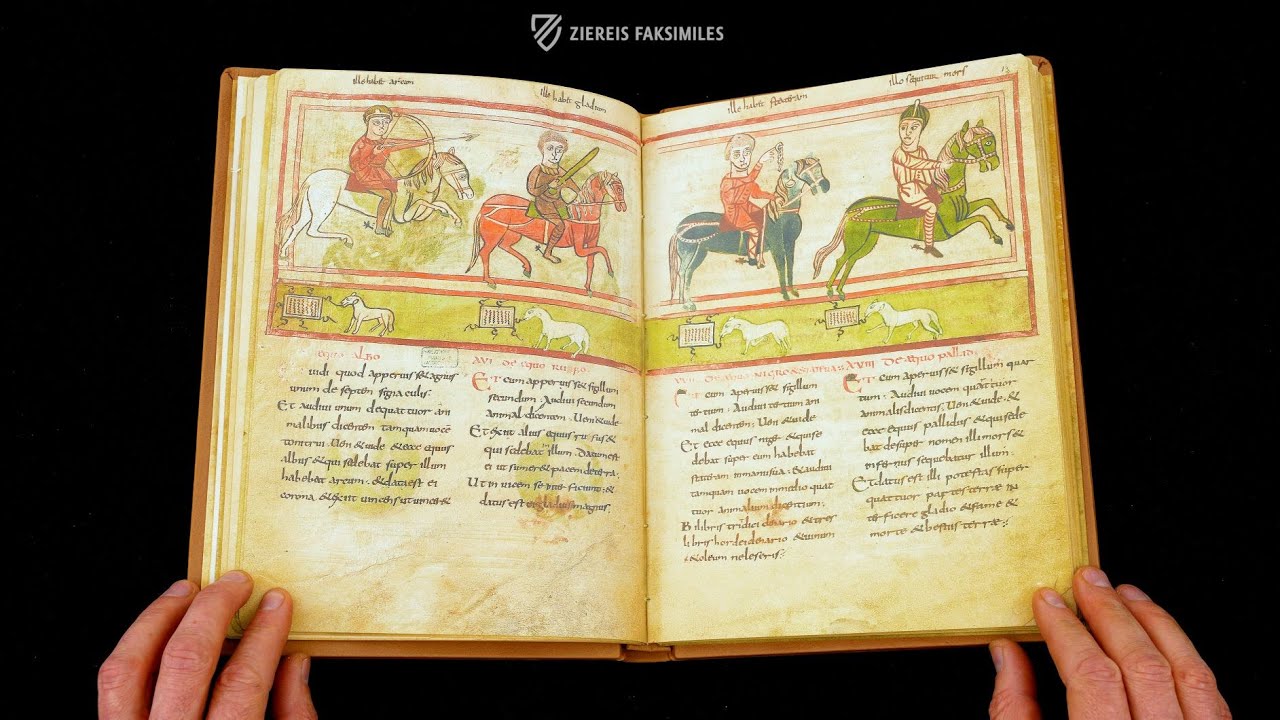

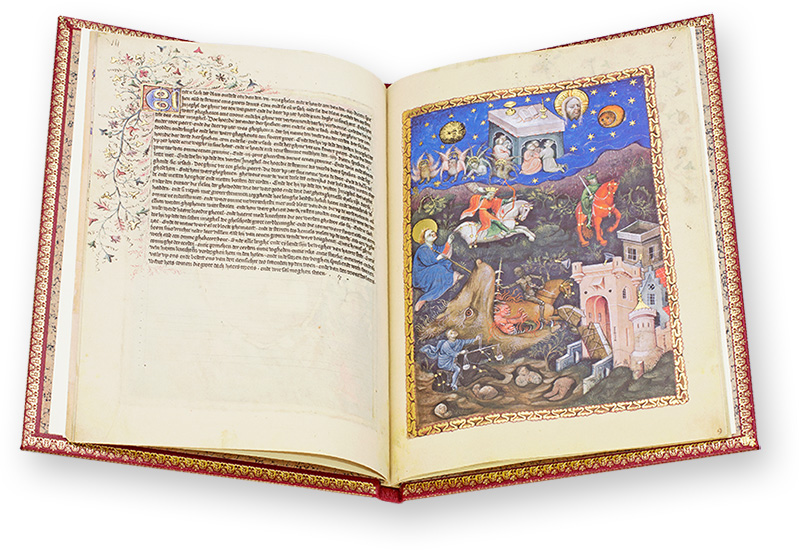

The First Horseman

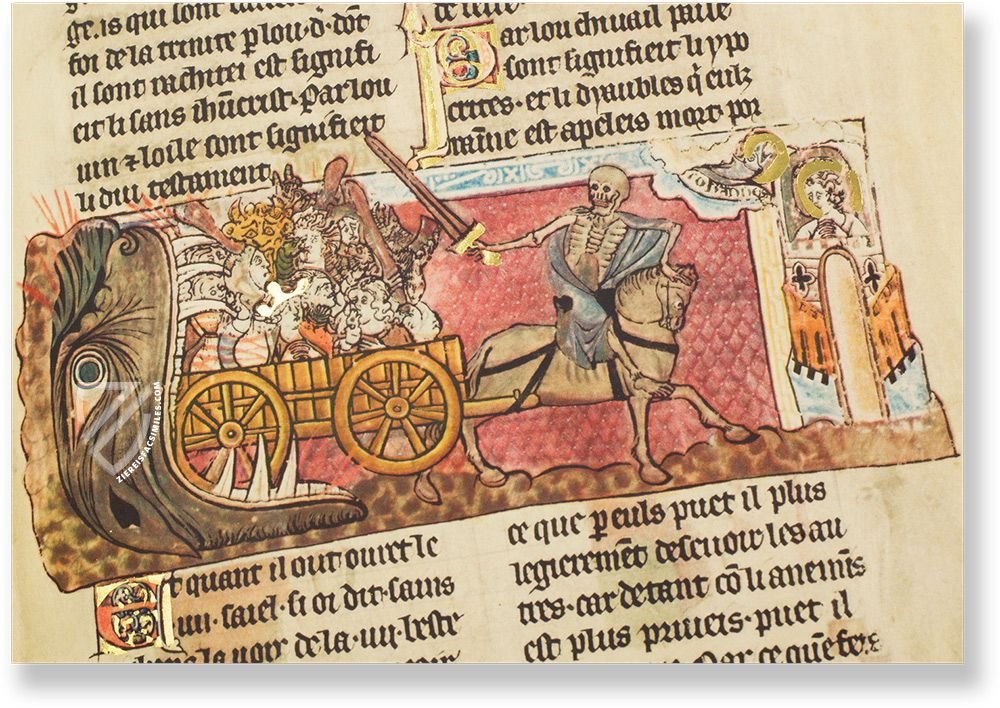

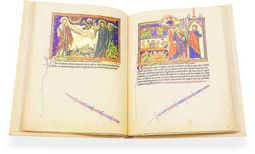

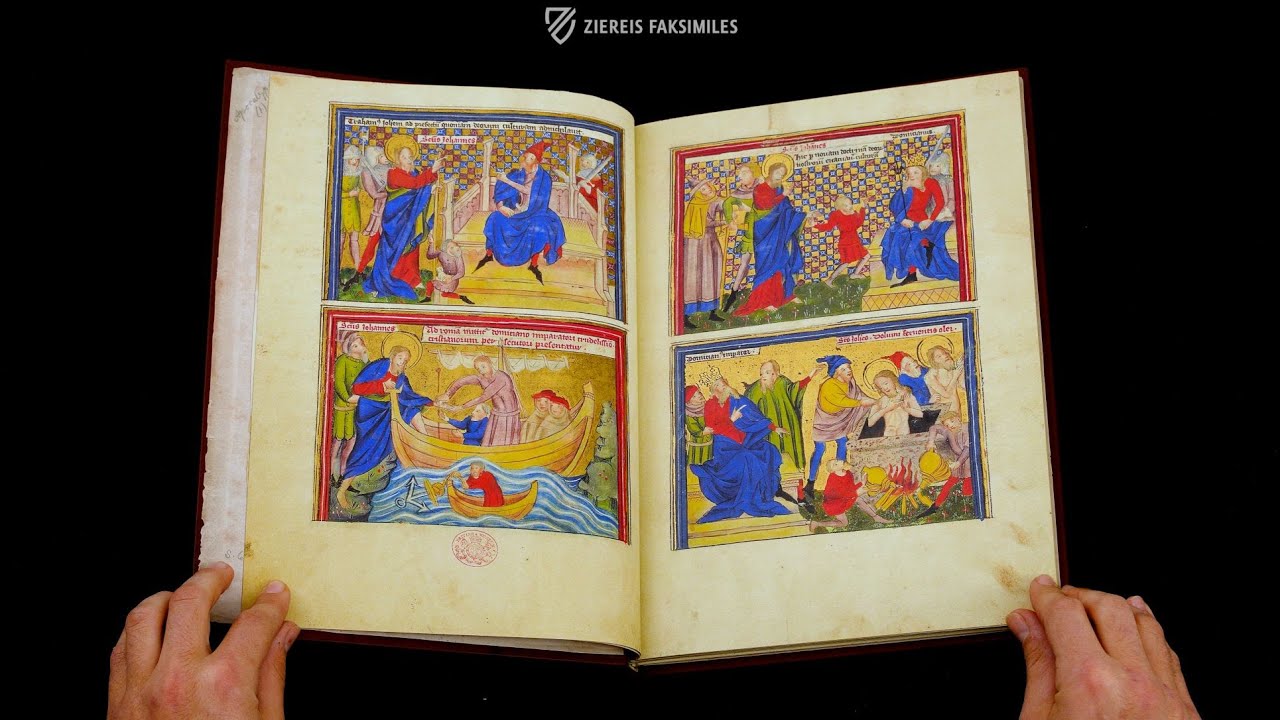

In the Book of Revelation, the Seven Seals unleash a series of cataclysms: “Now I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seals; and I heard one of the four living creatures saying with a voice like thunder, ‘Come and see’. And I looked, and behold, a white horse. He who sat on it had a bow; and a crown was given to him, and he went out conquering and to conquer.” (Rev. 6:1-2)

This fine miniature uses various patterns and gold leaf to give a timeless and spaceless feel to the naturally depicted figures, a typical aesthetic of Apocalypse manuscripts. The white horse looks forward with a stern countenance, front hoof raised like a warhorse on parade while the rider looks out from the page with a neutral expression as though resigned to his mission.

Splendor and Terror

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

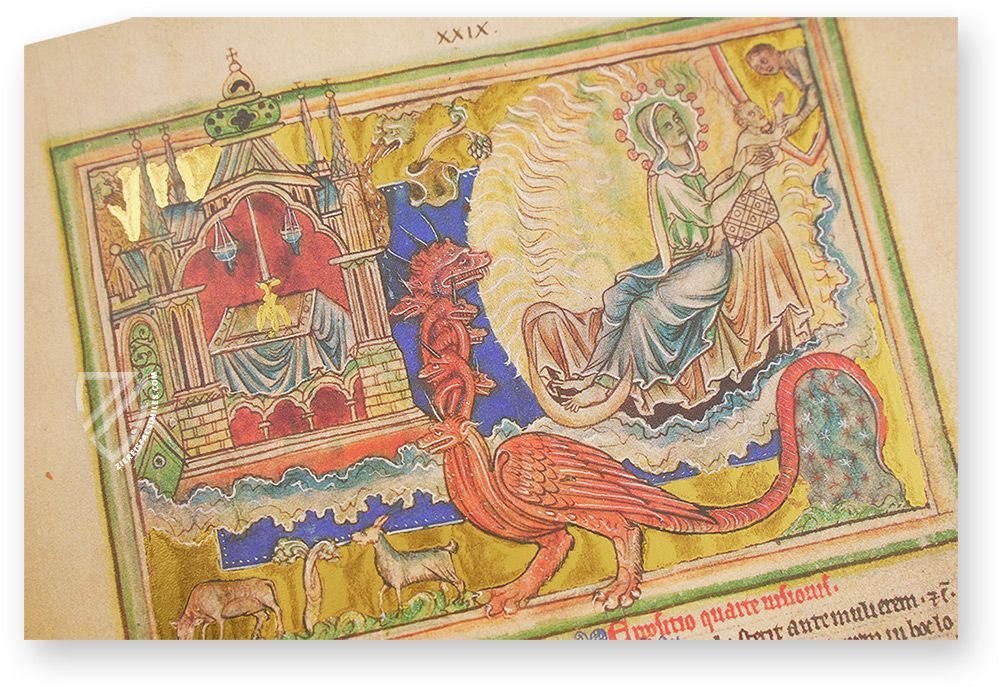

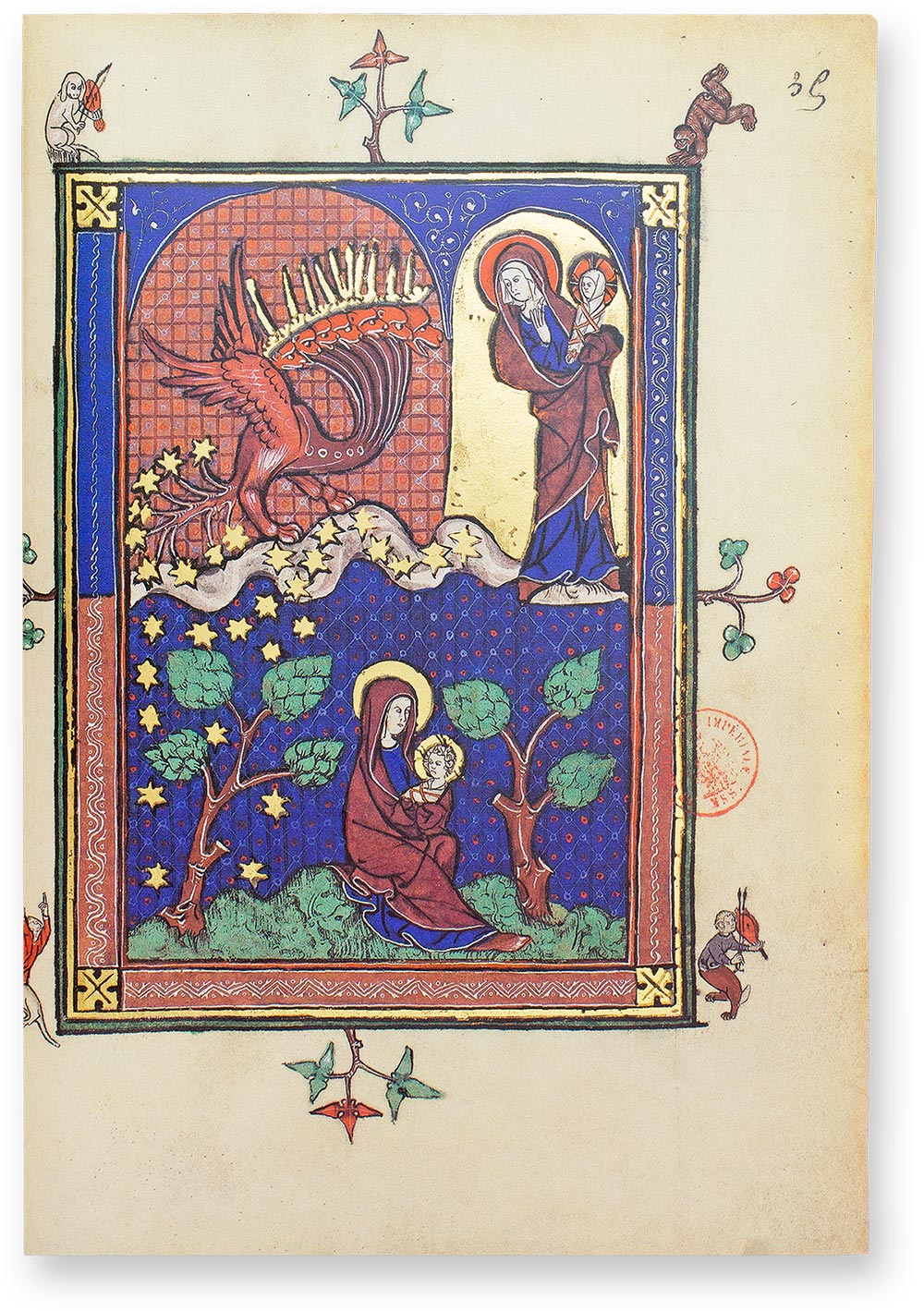

No other genre of medieval manuscript offers such fantastic and bizarre miniature paintings, all inspired by the kaleidoscope of imagery, numerology, and symbolism found in the Book of Revelation, more commonly known as the Apocalypse during the Middle Ages. Such texts contain the Revelation to John concerning the end of the world and the Second Coming of Christ.

It is full of symbolism, numerology, and various fantastical beasts, all of which is open to manifold interpretations ranging from futurists who take it as a literal prophecy to historicist perspectives that consider it to be something akin to social criticism, presumably having been written in either the 1st or 2nd centuries when persecution of Christians was rampant in the Roman Empire.

No other genre of medieval manuscript offers such fantastic and bizarre miniature paintings

To the facsimile

The imagery of the Apocalypse is often so strange and frightening that it would have been considered blasphemous or downright sinful were it not directly from a biblical text. These manuscripts afforded artists the artistic license to call upon the fullness of their talents, granting them an unprecedented freedom of creativity.

The enigmatic text of the Book of Revelation was among the most popular subjects for manuscript production throughout the Middle Ages and illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts enjoyed periods of popularity in various European lands with artistic traditions overlapping and influencing one another.

Experience more

Enrapturing Symbolism

To the facsimile

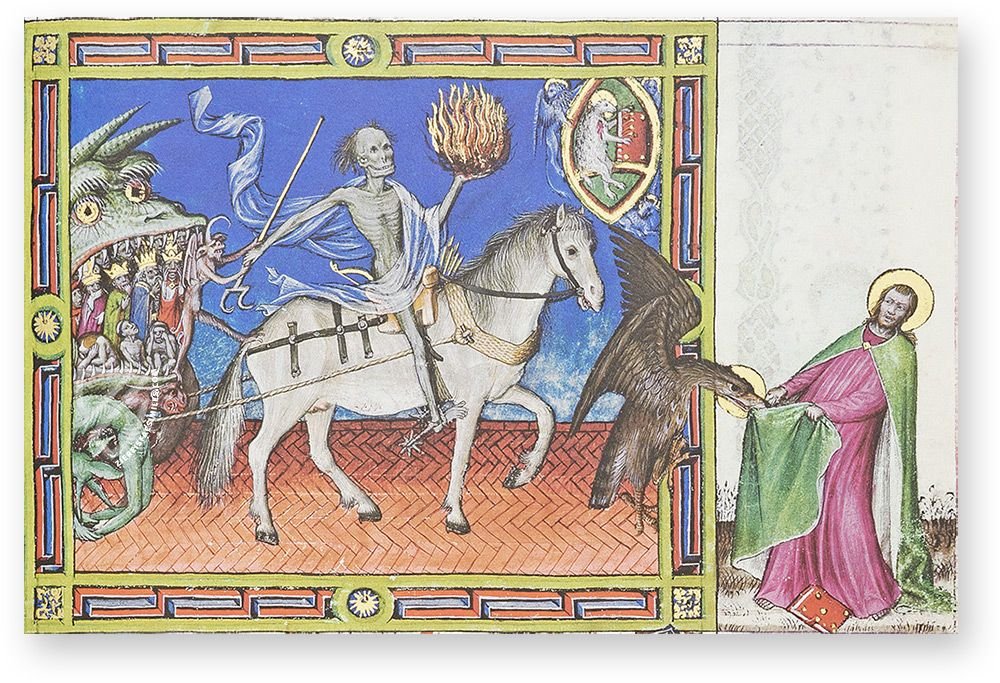

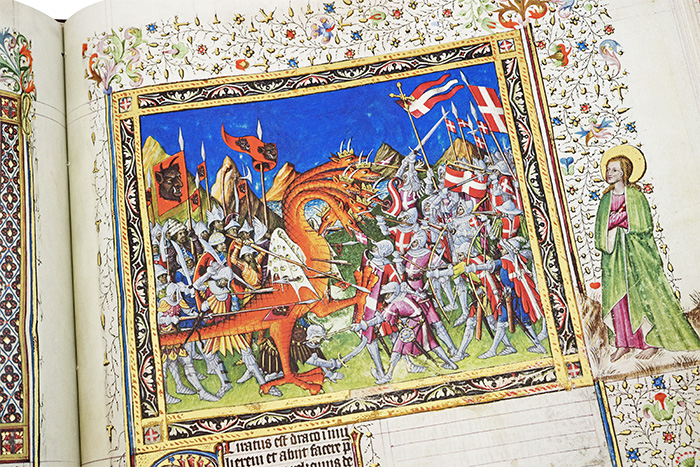

And when he had opened the second seal, I heard the second beast say, Come and see.

And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword.

Revelation 6:3-4

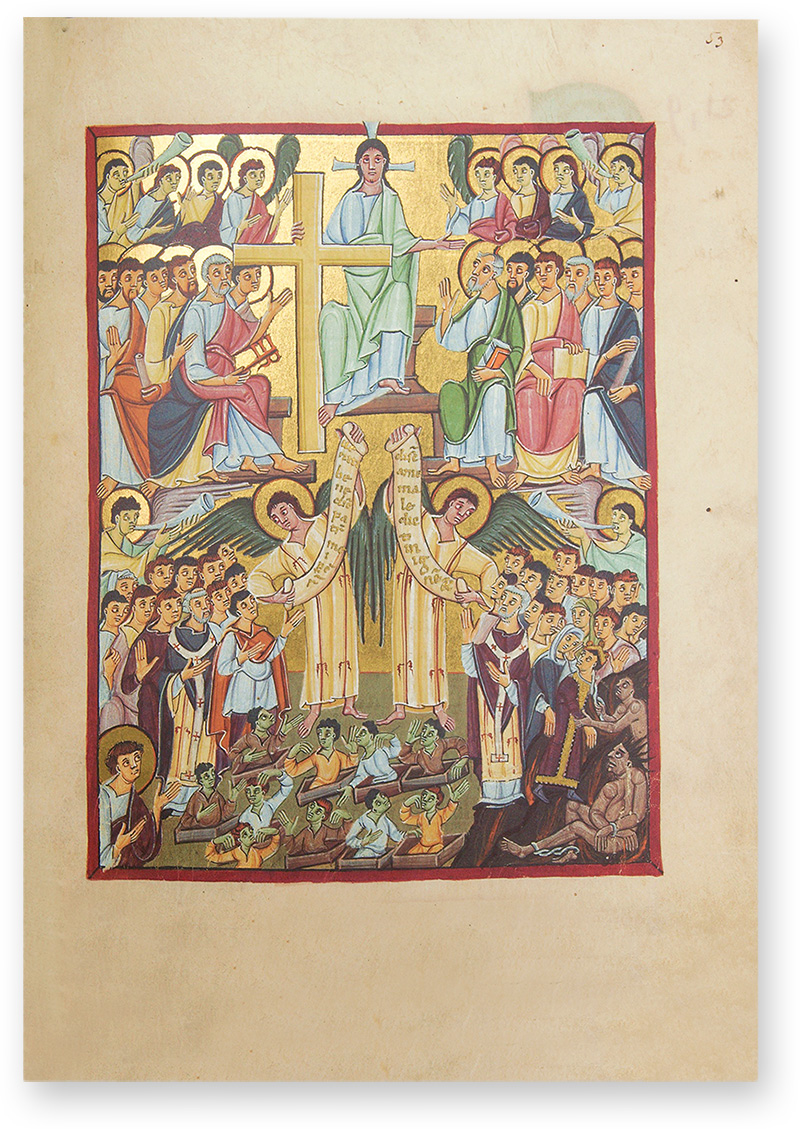

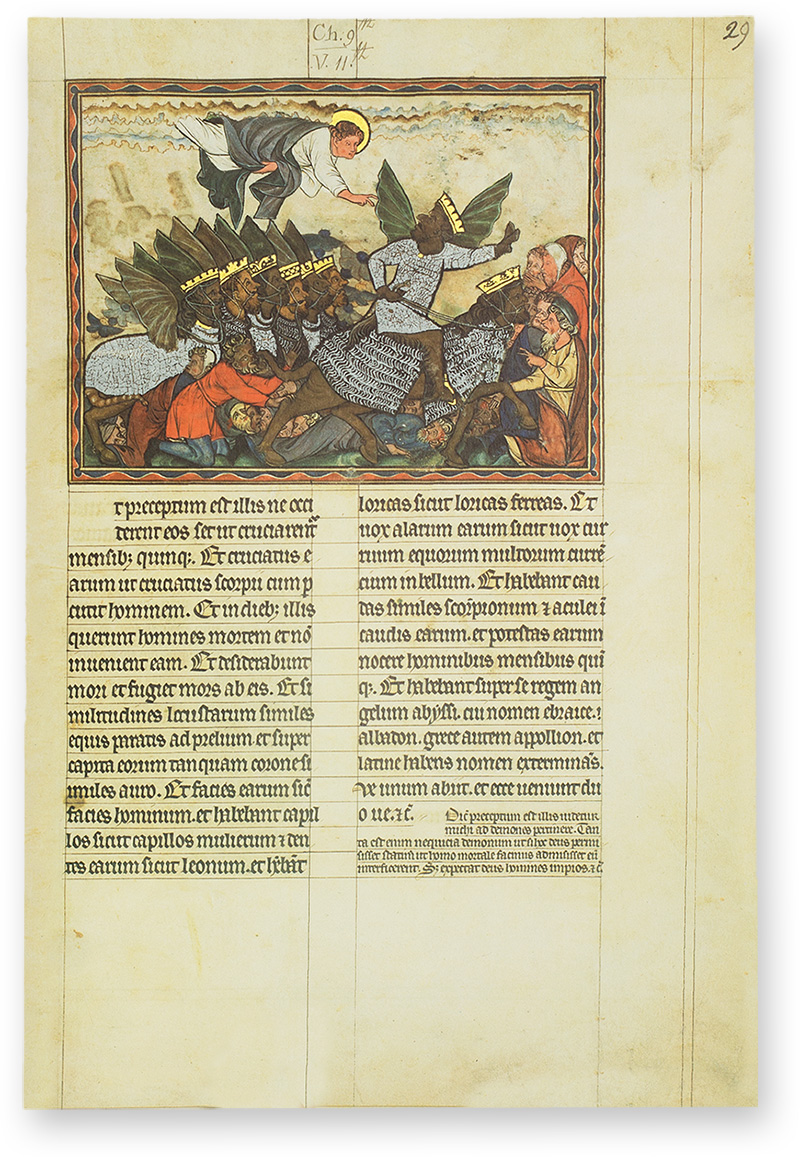

Strange figures, terrifying beasts, multi-headed monsters, broken seals, horsemen in the sky, trumpets, bowls, and recurring numbers and phrases – these symbols are woven together into the intriguing tapestry of the Apocalypse.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Even today, there is still no consensus on the meaning of John’s vision, which accounts for the enduring charisma of the text, it is a riddle that can never be completely solved, and yet the reader is able to discern enough to keep them looking, to keep them contemplating the meaning of this incredible story.

The addition of fantastical miniatures, historiated initials, and marginal decorations by some of the greatest artists of the Middle Ages only serves to magnify the charm and charisma of the text while helping the reader to visualize the oft-confusing events of the Apocalypse.

To the facsimile

Experience more

A Perennial Favorite

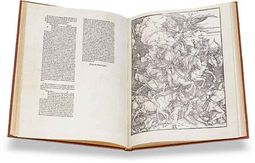

When Albrecht Dürer (1417–1528) was creating the haunting woodcuts of his own printed Apocalypse with Pictures, he was participating in a tradition that had endured for more than eight hundred years. This tradition even predated the publication of an Apocalypse commentary by the Spanish Saint Beatus of Liébana in the 8th century, which served as a catalyst for the increased production of these codices.

To the facsimile

The commentary was so popular that Beatus manuscripts can be considered an entire sub-genre of Apocalypse manuscripts unto themselves. 27 of these manuscripts, which were made over a period of some 500 years, have survived today. They represent some of Spain’s most prized cultural artifacts and are housed in the world’s most prominent museums and libraries.

Beatus's commentary on the Apocalypse evolved into its own sub-genre of Apocalypse manuscripts

Experience more

Over the Pyrenees and Across the Rhine

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

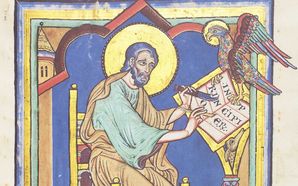

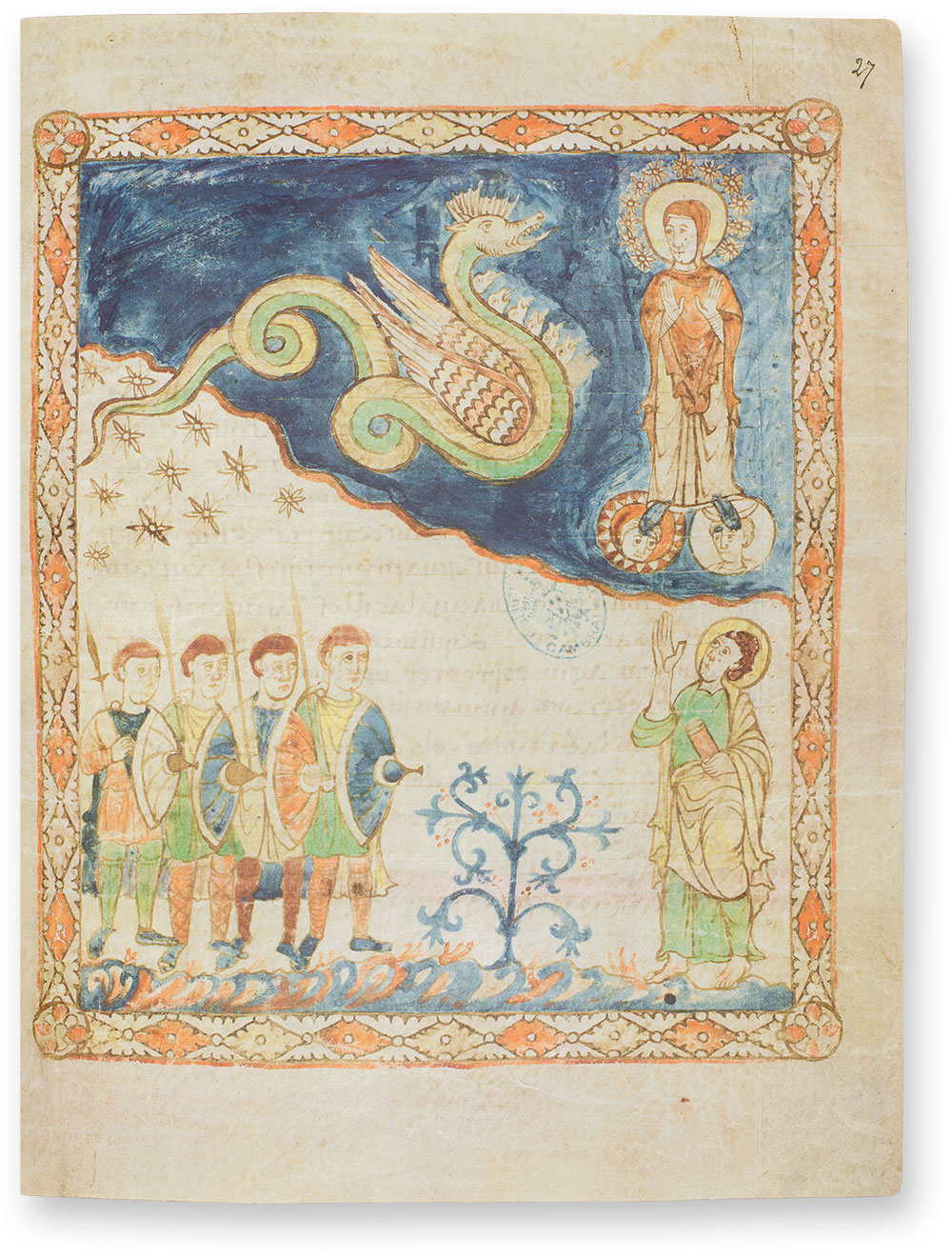

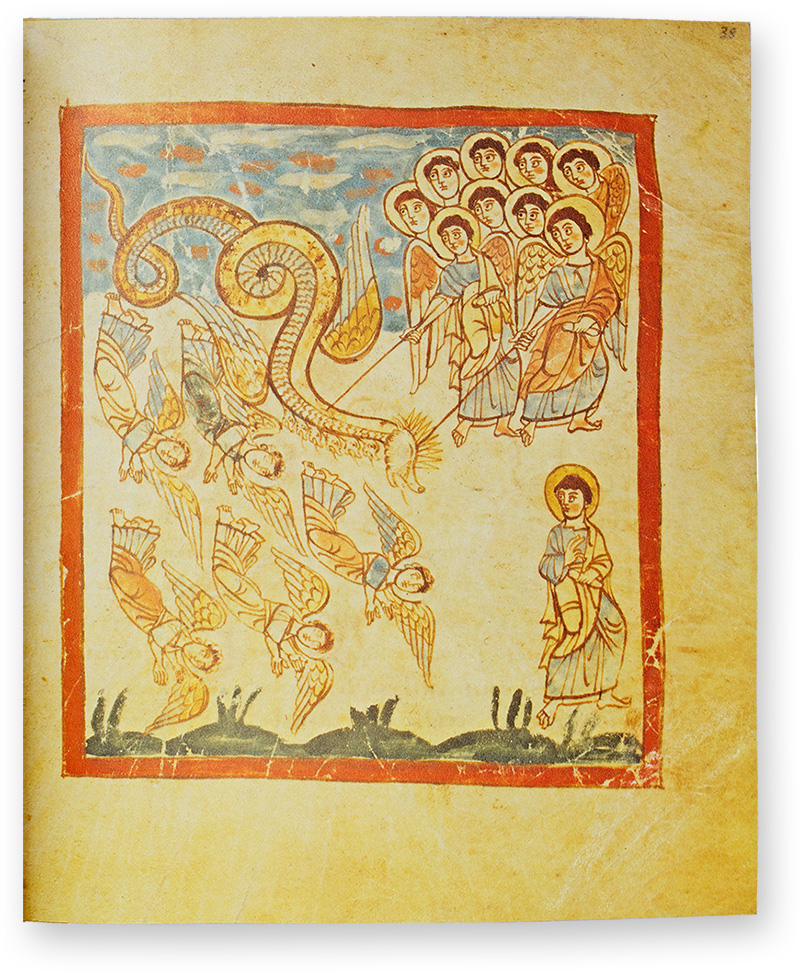

As book production flourished under the patronage of the Carolingians in Frankish scriptoria at Aachen, Lorsch, and Trier, so did Apocalypse manuscripts that are counted among the masterpieces of Carolingian illumination. The oldest and largest of these is the Treves Apocalypse (ca. 800) with 74 miniatures possessing an aesthetic that is Paleochristian and exhibits a strong Roman influence, especially with regard to the images of angels and demons that resemble Roman deities.

To the facsimile

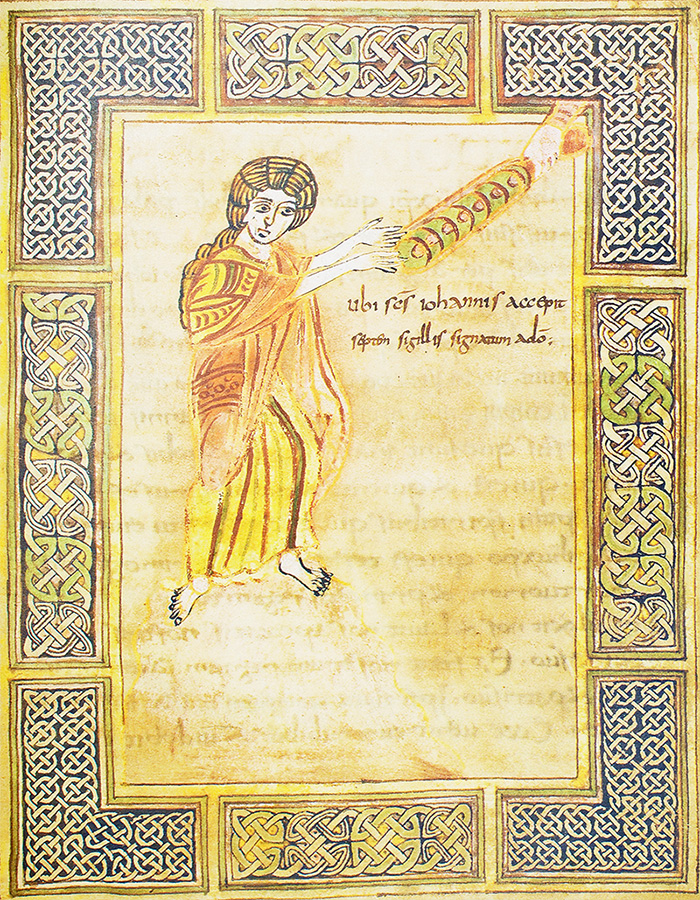

The Apocalypse of Valenciennes (ca. 800–25), named after its modern repository, made its own contribution by combining styles from Flanders and the Rhineland with some elements of insular illumination, as evidenced by the Celtic knot patterns in some of the frames. The popularity of Apocalypse manuscripts extended over the Rhine and their decoration would continue to develop during the epoch of Ottonian illumination.

Only one Apocalypse manuscript has survived from the Ottonian period

To the facsimile

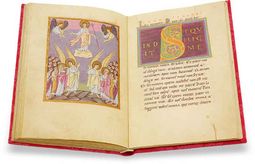

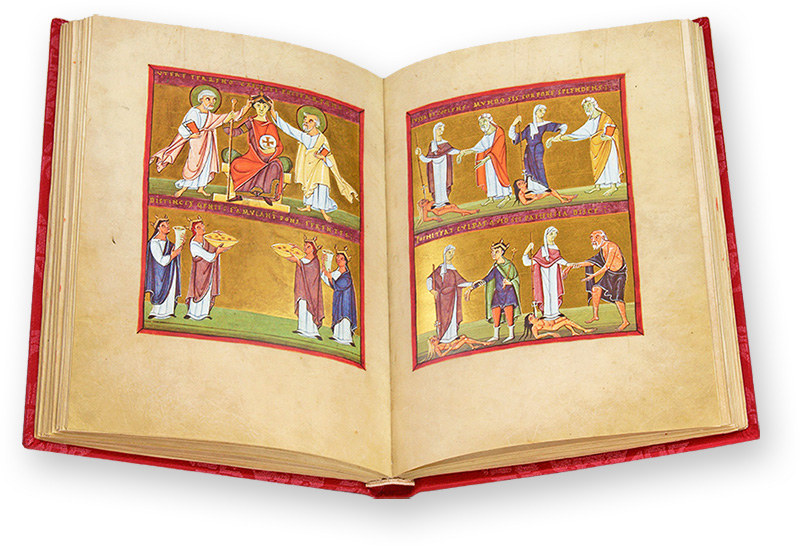

Although only one Ottonian Apocalypse manuscript has survived, it is no less than the Bamberg Apocalypse, considered to be the greatest masterpiece of the famous Reichenau Abbey and listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World International Register in 2003. It features 57 miniatures with incredible burnished gold backgrounds in the Byzantine style and initials embellished with Celtic knots and other artistic devices from insular illumination.

The incredible manuscript is the result of imperial commissions and originated ca. 1000-1020, initially at the behest of Emperor Otto III, but had to be completed after his unexpected death under the patronage of his successor, Henry II.

To the facsimile

Experience more

Proliferation in England

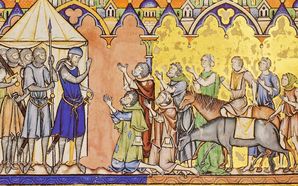

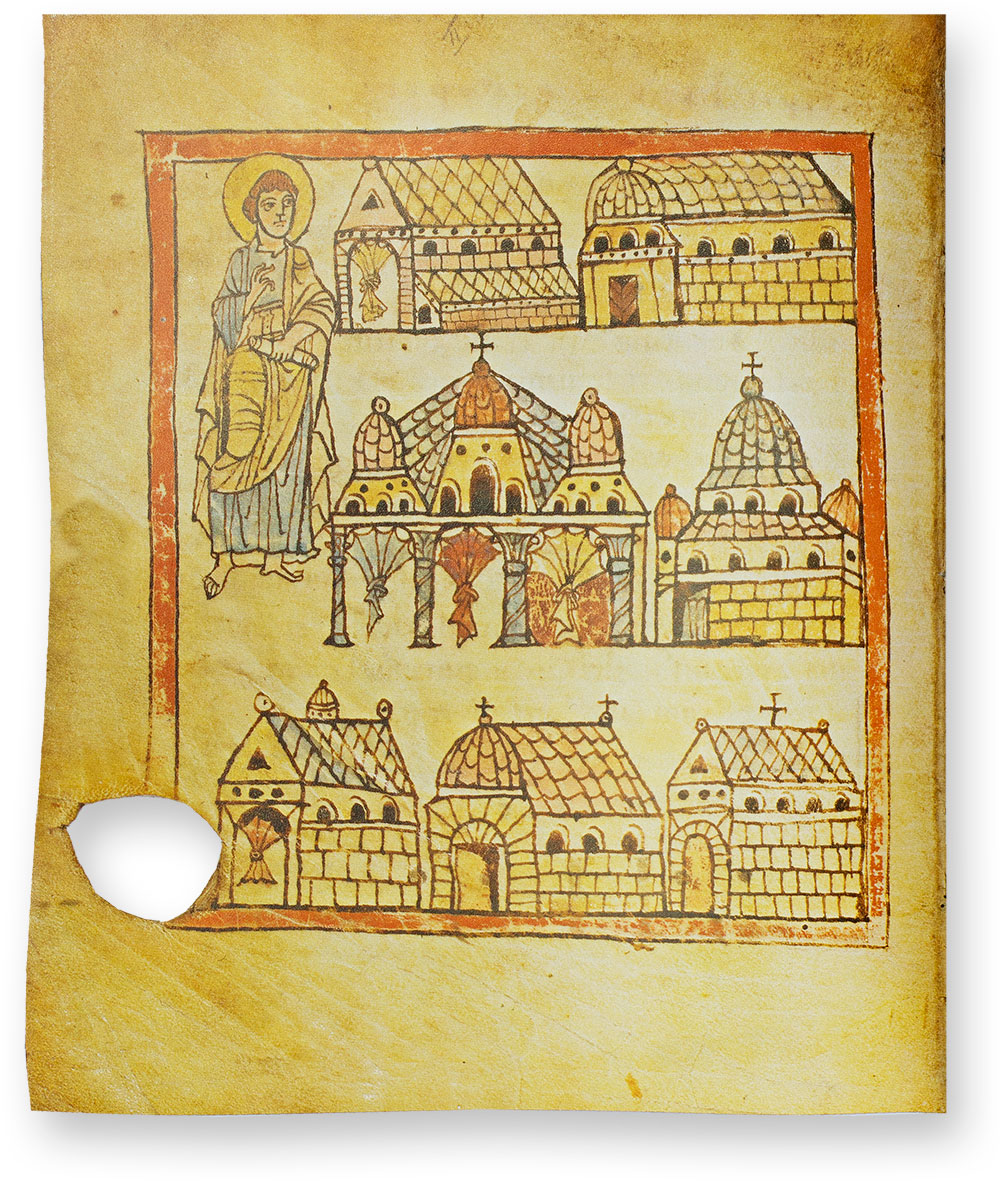

The center of Apocalypse manuscript production shifted again during the Romanesque period when they came to England, which produced some of the finest and most famous of these manuscripts during the Middle Ages, with works of the English Gothic held in particularly high regard.

Some of the finest Apocalypse manuscripts were created in England

To the facsimile

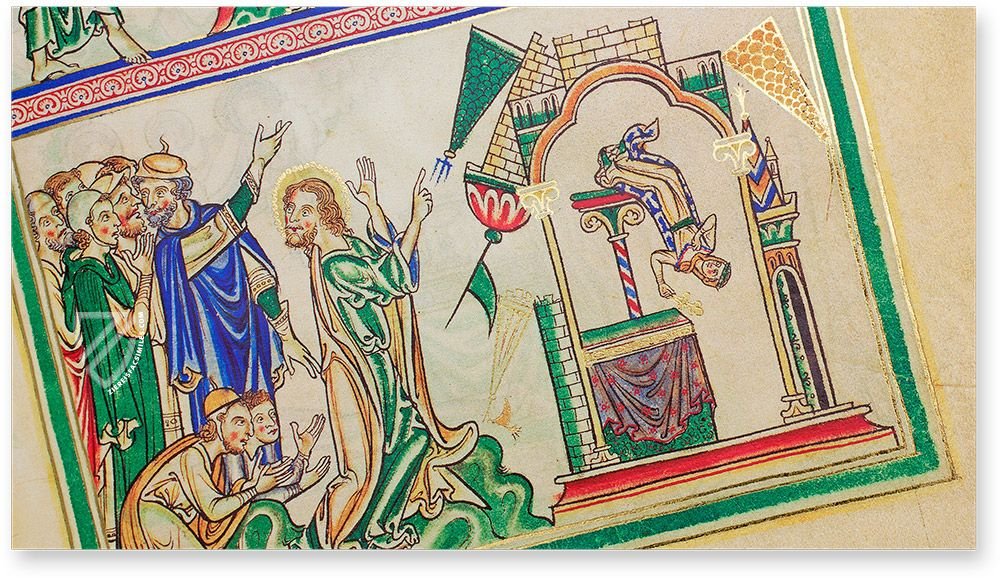

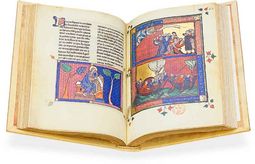

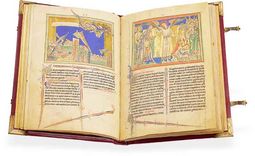

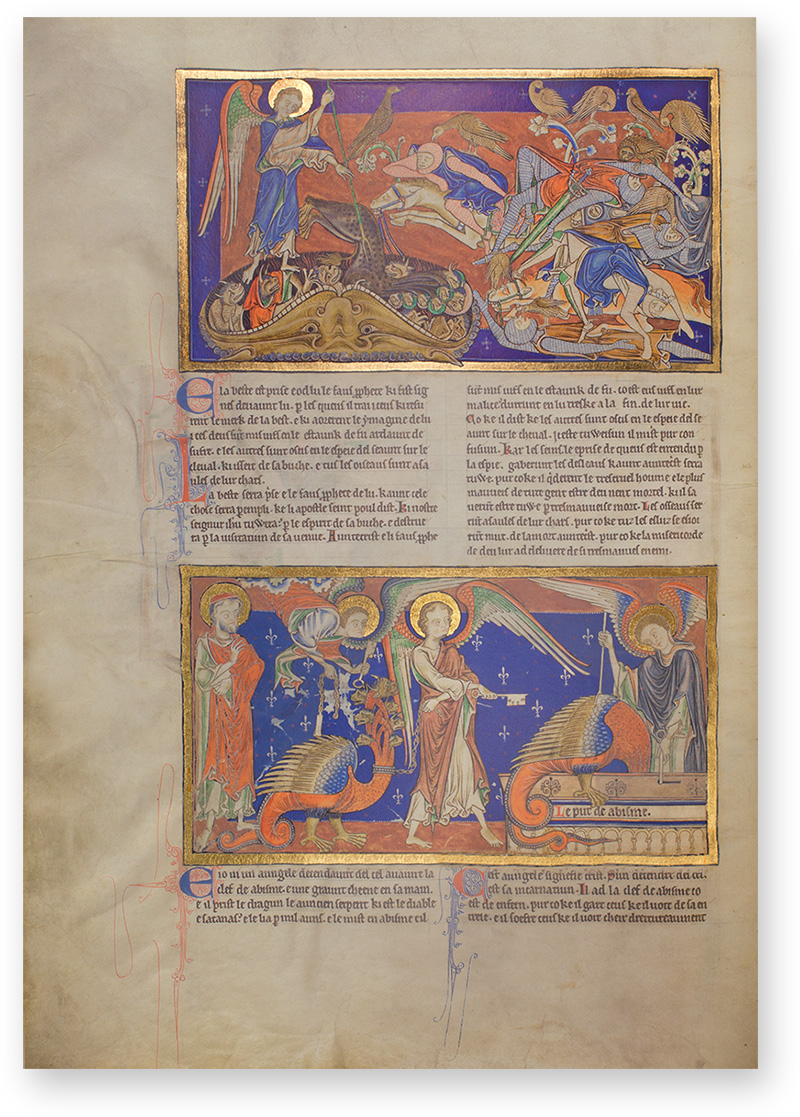

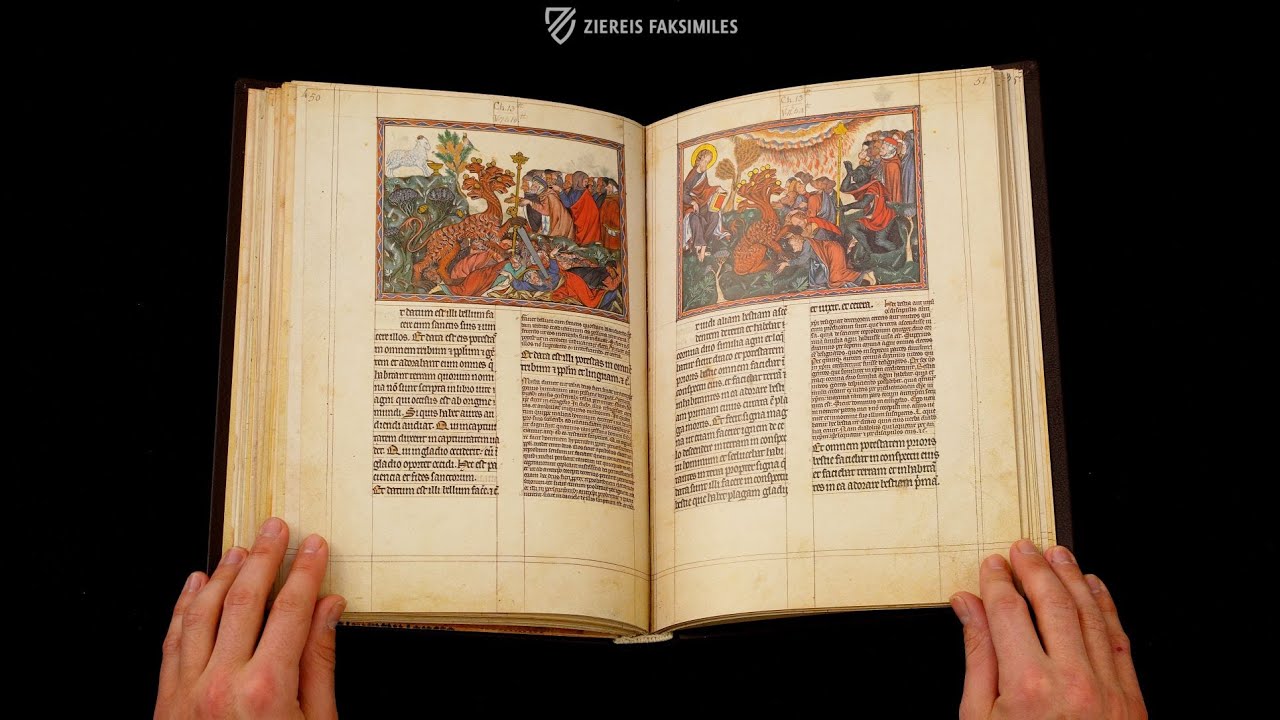

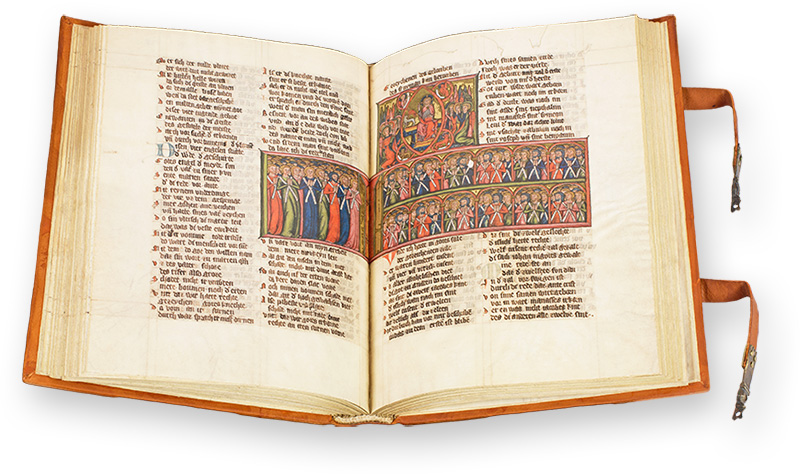

The Oxford Apocalypse (ca. 1272) marks a transition in artistic style, combining established Romanesque aesthetics with the newer, airier, more elegant Gothic. It is also an early example of the image program of English Apocalypse manuscripts: each of its 97 gilded half-page miniatures is situated in the upper register of the page above the text narrating it.

This image program is generally followed, albeit with some innovations, in other English Apocalypse manuscripts from the mid-13th century, such as the Paris Apocalypse by the Master of Sarum who illuminated all of its 100 pages, or the Apocalypse from Lambeth Palace with its splendidly burnished gold backgrounds. These English manuscripts not only stand as monuments of medieval illumination, but even served to inspire a new generation of continental Apocalypse manuscripts.

Experience more

The Apocalypse Returns to the Continent

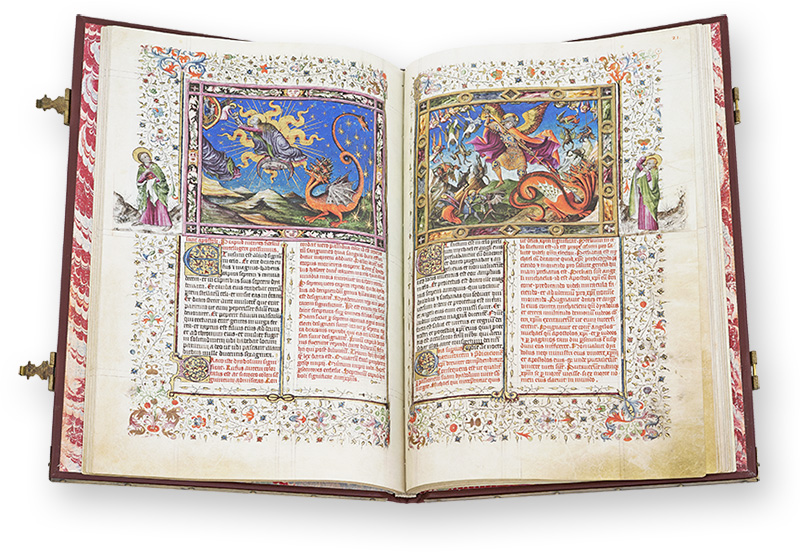

The so-called Flemish Apocalypse originated ca. 1400–1410 and altered the English aesthetic by replacing the half page miniatures in register with full-page miniatures on the recto and the corresponding text opposite on the verso and marks another artistic transition, this time from Gothic to Renaissance.

To the facsimile

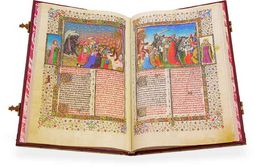

Another late medieval masterpiece was created by the finest French miniaturists of the 15th century: Jean Bapteur (active 1427–58), Péronet Lamy (d.1453), and Jean Colombe (ca. 1430 – ca. 1493) all participated in the decoration of the Apocalypse of the Dukes of Savoy over a period of 60 years.

This ornate manuscript keeps the English image program of miniatures in register above the text, but incorporates the exuberance of the French Gothic style and combines it with the emerging artistic devises of the Renaissance such as increasingly ornate bordures and the use of perspective.

A combination of the ancient picture program and the artistry of the French Gothic style

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The Apocalypse and the Printing Press

Apocalypse manuscripts continued to be popular with the emergence of incunabula in the 15th century, and the printing press helped them reach a new level of circulation in Europe. Originating from the Netherlands or the Rhineland ca. 1460, the Apocalypsis Johannis, also known at the Estense Apocalypse, features 96 full-page woodcuts, sometimes split into two in register, all colored by hand and filled with symbolism.

There are indications of the coming Reformation in their imagery, particularly as the clergy are assigned no grace or respect in it and are punished for their sins along with the rest of humanity.

To the facsimile

In many apocalypse incunabula, the coming reformation is already foreshadowed in the imagery

To the facsimile

The Apocalypse with Pictures by Albrecht Dürer is considered to be one of the masterpieces created by the greatest artists of the German Renaissance and already was by contemporaries – its publication was a huge financial success. Dürer’s 15 miniatures in black and white, his depiction of the Four Horses of the Apocalypse being the most famous among them, are gripping, spooky, incredibly detailed, and leave a lasting impression.

Far from signaling the end of the popularity of Apocalypse manuscripts, the tradition flourished and spread to Eastern Europe, Russia in particular, where they continued to produce illuminated Apocalypses up to the beginning of the 20th century.

To the facsimile

Experience more