Books of Hours

The book of hours, the most beloved type of medieval manuscript, is a specially-designed prayer book for personal use both in private and in public masses based upon the “offices” or official prayers that were to be said at different intervals of the day – hence the name.

These were typically made for laypersons in artists’ workshops rather than monastic scriptoria, and as such the actual wording of the prayers contained in them can vary widely from region to region. Most were small enough that they could be carried on one’s person, like the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux and were decorated in such a way that they were also fashion accessories. As such, they were highly personalized and usually featured a dedication page with their escutcheon and might even be portrayed in one or more miniatures in the text.

Some of the first big-name artists like the Limbourg Brothers, Simon Bening, and Gerard Horenbout emerged as a result of this popularity, although some of the greatest masters remain anonymous, known only by their names of convenience. The personalized book of hours is a useful window into the lives and perceptions of some of the most important figures of the Middle Ages.

Demonstration of a Sample Page

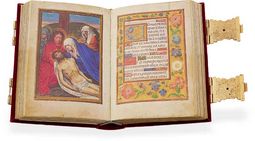

Bedford Hours

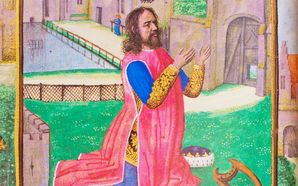

Owner Portrait

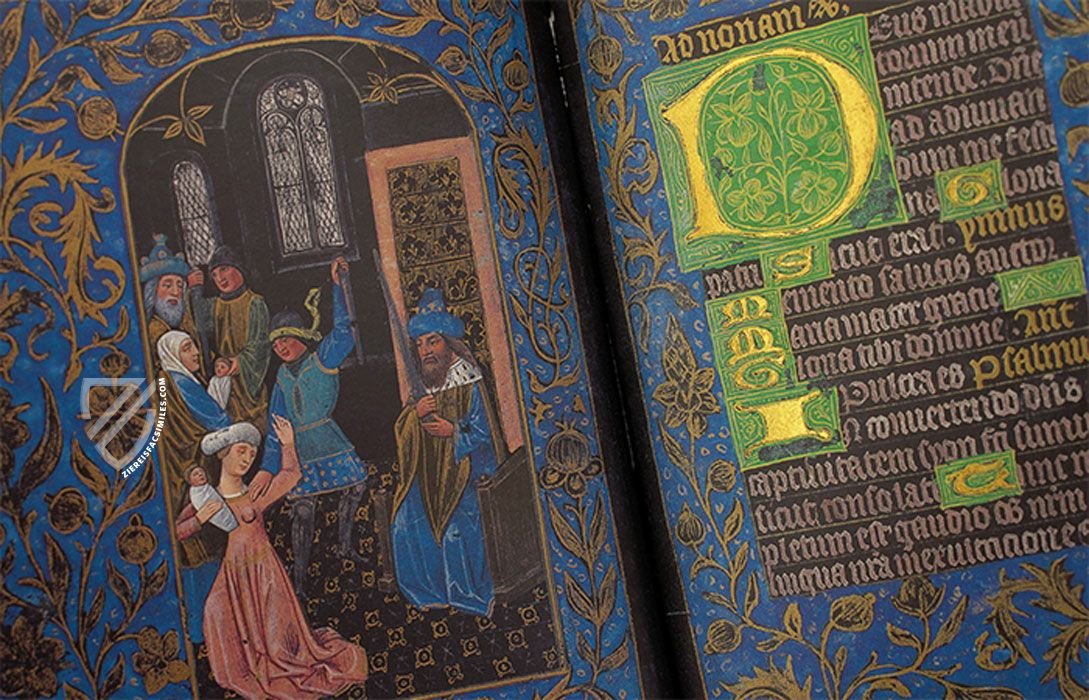

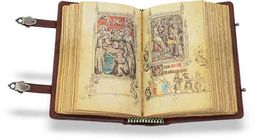

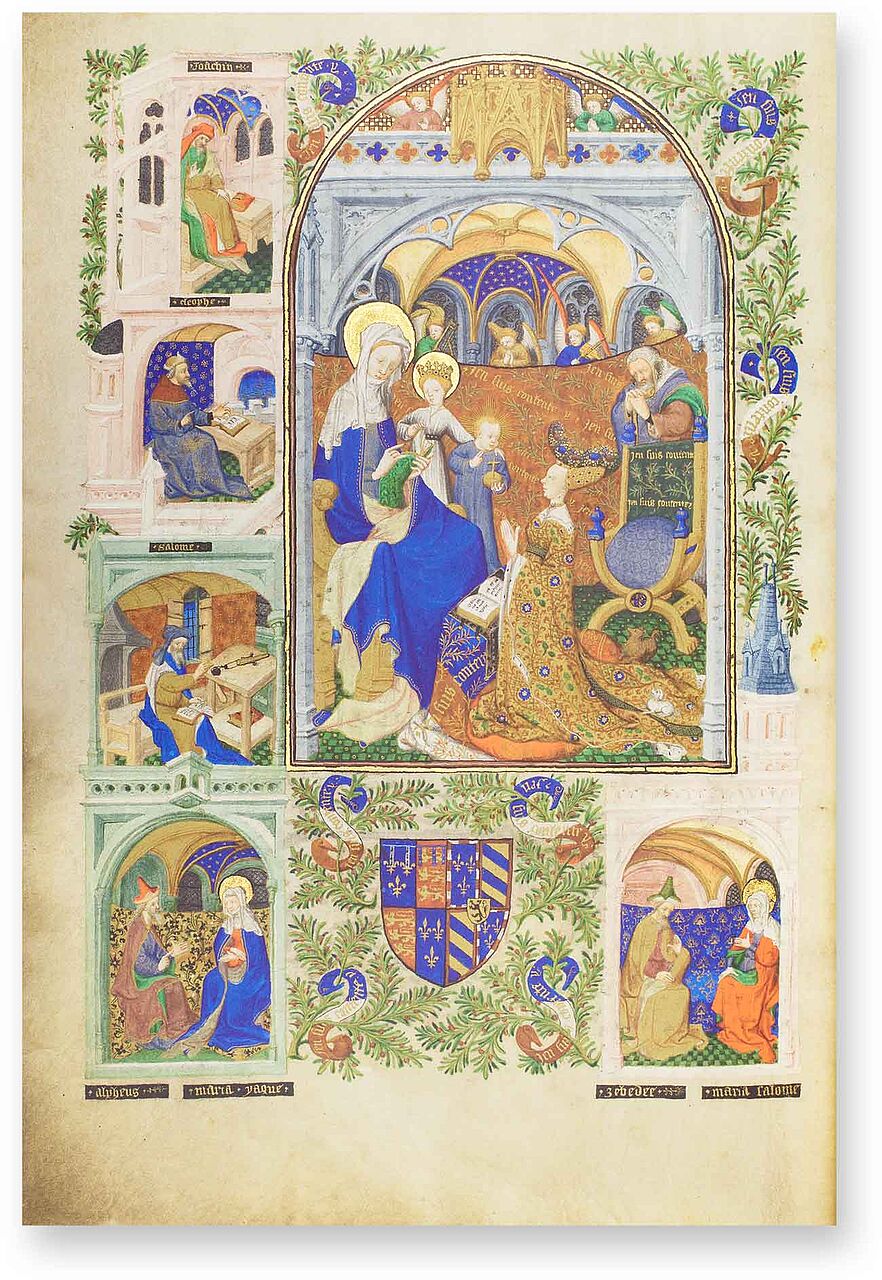

Although consisting of biblical texts and prayers to be said throughout the day, books of hours were intended for laypeople, usually those who could have them made according to their personal specifications. One such person was Anne of Burgundy, who either received or gave this manuscript as a wedding present to mark her union with John of Lancaster, the Duke of Bedford.

Duchess Anne is kneeling before St. Anne in this masterpiece, part of arguably the finest book of hours ever created and a product of the famous Bedford Workshop. It is also evidence of a rare love match between the powerful English regent and the wealthy Burgundian princess, shown dressed in the finest brocade. Miniatures of biblical figures and her coat of arms fill out the page.

“Seven times a day do I praise thee because of thy righteous judgments.”

Psalm 119:164

Of all the manuscripts to have survived the Middle Ages, no other genre exists in numbers that can even approach the book of hours. The reason for this is that personal devotional codices were the most popular kind of manuscript during the Late Middle Ages, when book production and artistry reached its zenith. These were usually written in Latin, although there are some vernacular specimens, particularly in Dutch. Unlike a normal prayer book, which would often be kept in a room set aside for prayer or even a small chapel, a book of hours was meant to be carried on one’s person throughout the day and intended as an aide for participating in public church services. Moreover, their name comes from the fact that they contain prayers for specific times of day, called offices because they are official prayers of the Catholic Church and are ordered according to the liturgy.

That being said, their texts were not controlled by the church and the production of books of hours mainly occurred in the ateliers of secular artists. Therefore, prayers could vary – particularly between regions – and some books of hours had prayers crossed out by clerical censors in later centuries, especially during the Counter Reformation. The book of hours was a central part of daily life for those possessing the piety and wealth. Some are considered to be true masterpieces of medieval illumination and occidental art as a whole, and were the commissions of royalty. The finest of these books have had long and often turbulent ownership histories because of their desirability, which is only increased with each successive famous owner.

The Origins of Canonical Hours

Christian canonical hours have their roots in the Jewish practice of zmanim – praying at set times of day. This practice was adopted and passed down by the Apostles, as is told in the quote from the Book of Acts above. Two traditions began to emerge in Jerusalem and Constantinople ca. 500, which were eventually reconciled in the 8th century, thus yielding the complex offices found in books of hours.

“Now Peter and John went up together into the temple at the hour of prayer, being the ninth hour.”

Acts 3:1

The offices were originally set at intervals of three hours according to the Roman practice of signaling various times of the day with a bell at the forum marking the beginning of the workday at six o’clock, its progress at nine, the noon lunch break, the resumption of work at three, and concluding the business day at six in the evening. These were appended, and the offices of canonical prayers eventually numbered eight in total.

These were appended, and the offices of canonical prayers eventually numbered eight in total. Originally, a number of texts were needed to perform these prayers including a Psalter, Lectionary, Bible, and a hymnal, but these were combined into breviaries by the 12th century, of which the book of hours is a condensed and abridged version that first began to emerge in the 13th century. Therefore, the Psalter is the grandfather of the book of hours, and was replaced by it as the most popular type of luxury manuscript in the 14th century.

What is in a Book of Hours?

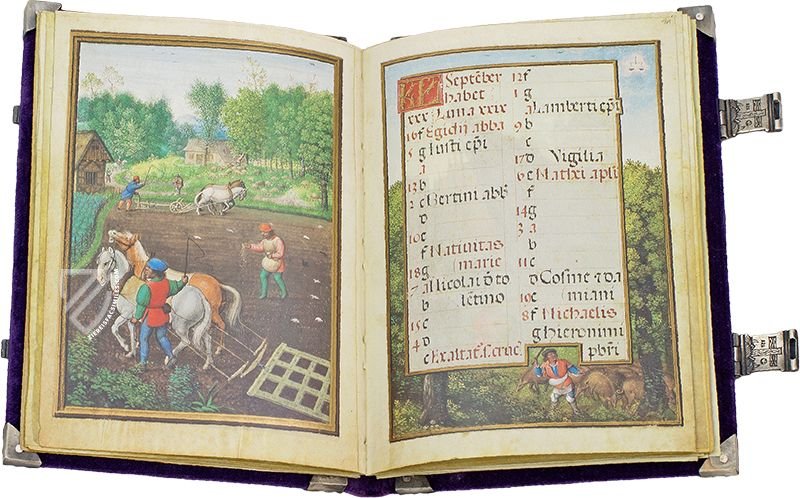

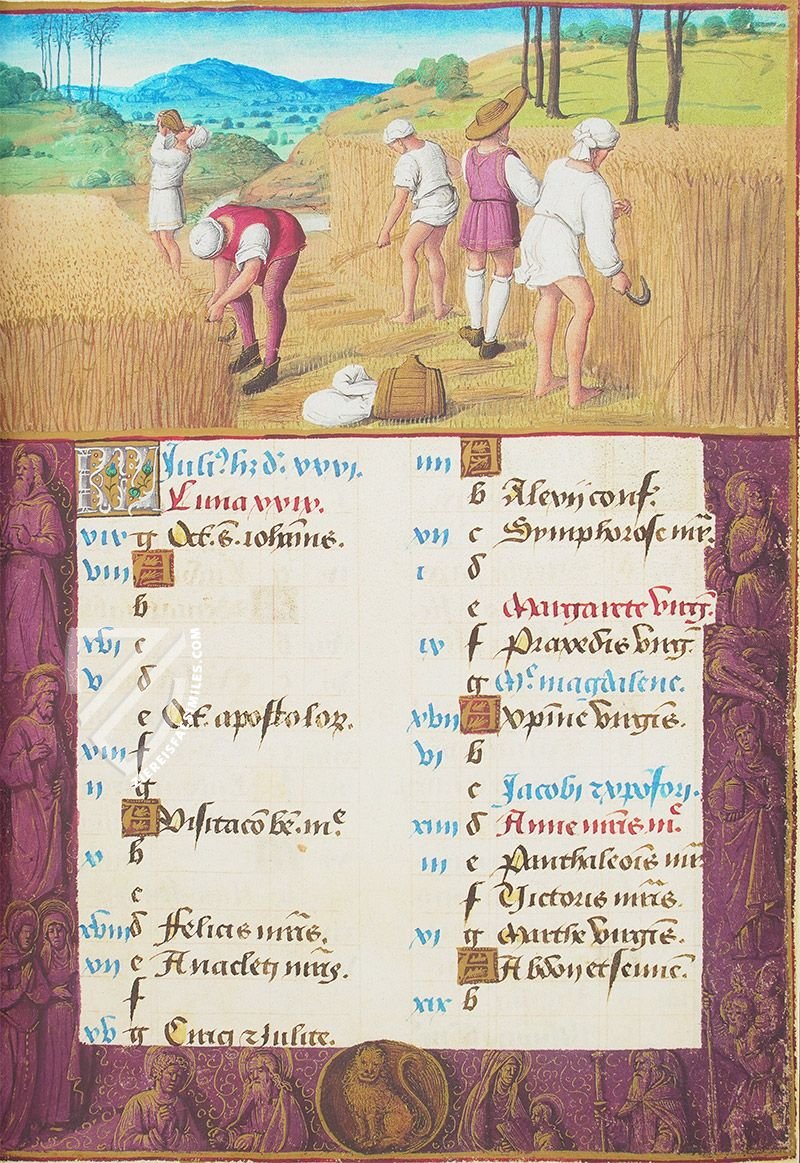

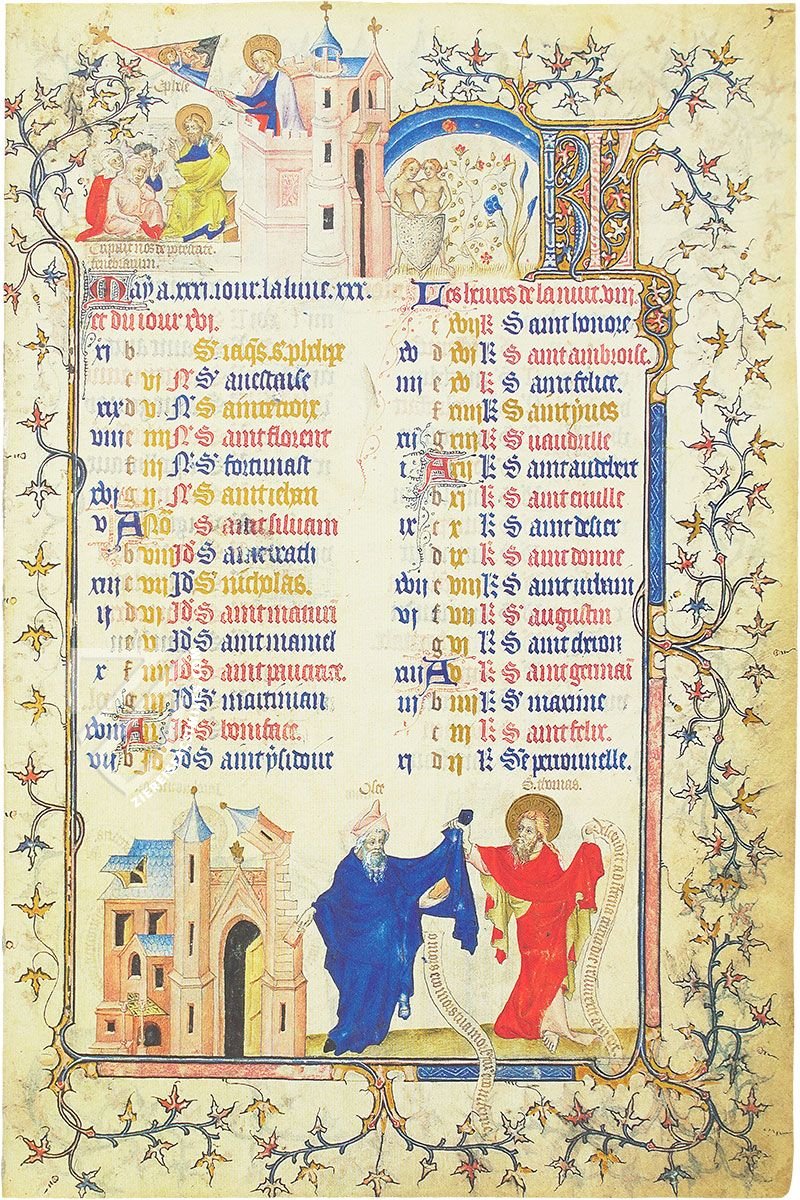

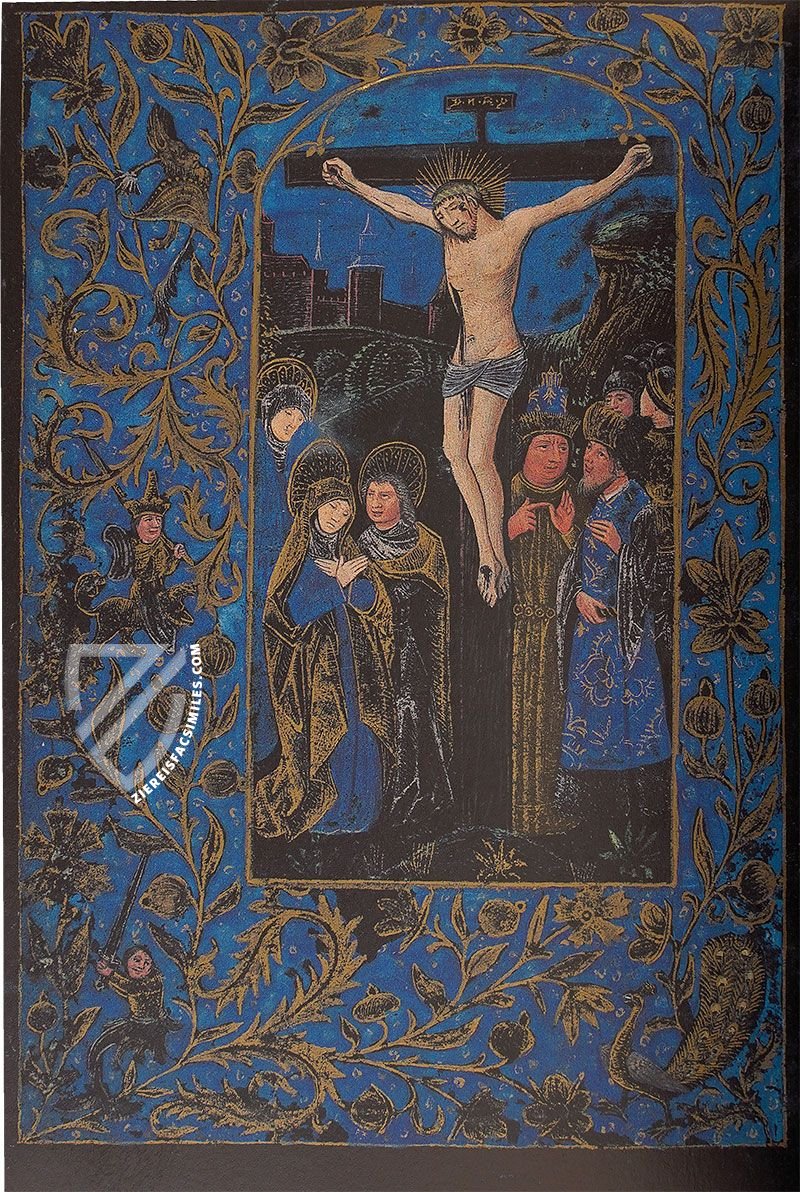

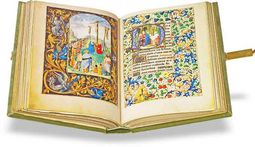

The structure of the book of hours was fairly uniform because they were intended to follow the liturgy and serve as an aide while attending mass. They usually open up with a series of calendar pages, often elaborately decorated. These liturgical calendars will contain information about important dates like holidays and saint’s days and often depict “labors of the month” – the typical activities associated with that time of year, especially with respect to farming and other rural activities. Later manuscripts included signs of the zodiac and astrological information.

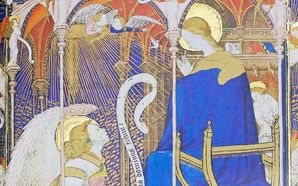

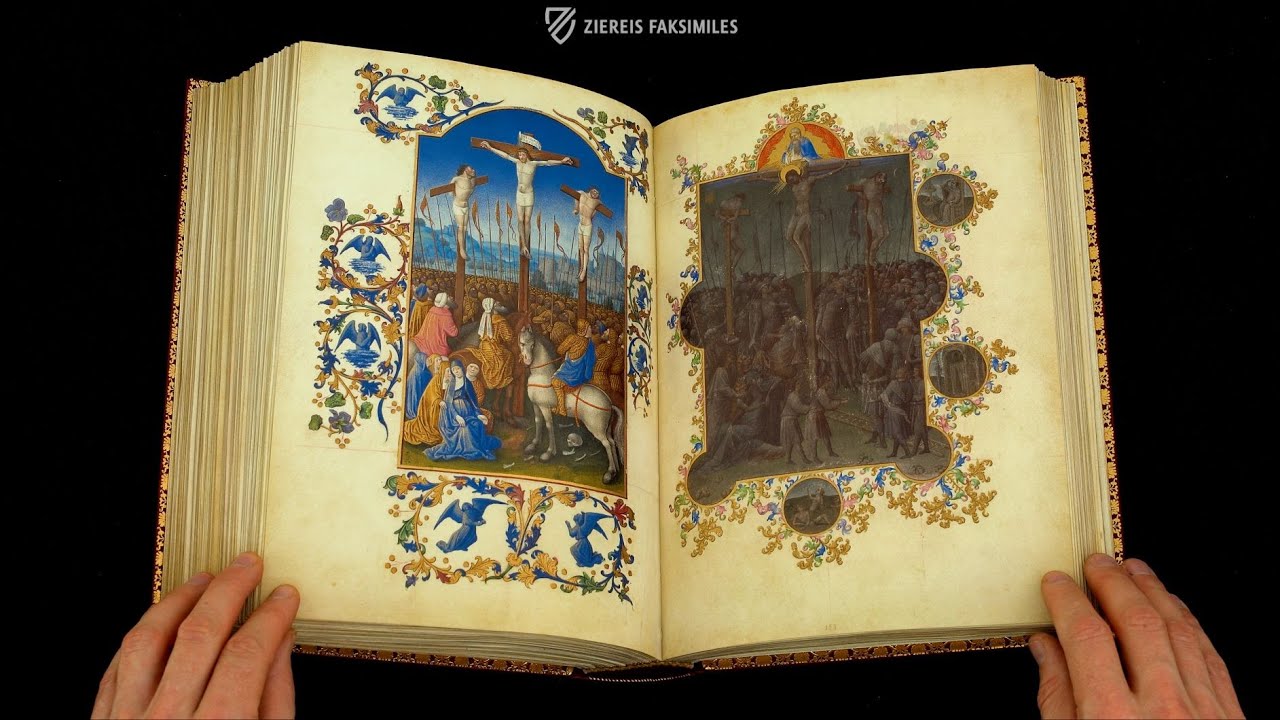

The offices (Office for the Virgin Mary, Office of the Cross, Office for the Dead, etc.) typically come next and are accompanied by relevant excerpts from the Gospels and Psalms, the Litany of Saints, and other prayers. Illuminated manuscripts often depicted the cycles of the Life of the Virgin Mary or the Passion, these were also fairly standardized but the variation in technique and style between different parts of Europe and over several centuries makes these cycles incredibly useful for comparing and contrasting various artistic schools. This combination of a uniform underlying structure and personally-customized artistic furnishings is part of what makes the books of hours so attractive and useful for researchers.

Popularity and Fashion

To the facsimile

A book of hours was more than a devotional tool, it was a fashion statement, and was not only an indication of one’s piety, but of wealth and sophistication as well. These codices were usually small and designed to be carried on one’s person publically, often on a decorative chain or in a custom-made pouch. Far from being the sole prerogative of men, a book of hours was a common wedding present to the bride, either from her betrothed or a relative. Often contained in sumptuous bindings of leather, velvet, or silk with gold clasps and fittings, sometimes set with precious gemstones, the luxury book of hours was a fashion accessory and a status symbol.

The gender of the owner is often indicated by the style of artwork and the selection of prayers, if not by a portrait, coat of arms, or other personal insignia. The Psalter had been the most popular type of illuminated manuscript since the time of Charlemagne, who personally commissioned them, but these began to decline in popularity during the High Middle Ages in favor of the book of hours, which also contained the Psalms in addition to the other texts necessary for the recitation of canonical hours.

Experience more

The Golden Age Begins

Although there are wonderful books of hours from the 13th century, like the De Brailes Hours by the English illuminator William de Brailes, and the 14th century, like the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux by Jean Pucelle, their popularity and production exploded ca. 1400. The most important figure with regard to this flowering at the dawn of the 15th century was Jean, Duc de Berry, who owned the splendid Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, commissioned by King Charles IV of France for his wife, after whom the manuscript is named.

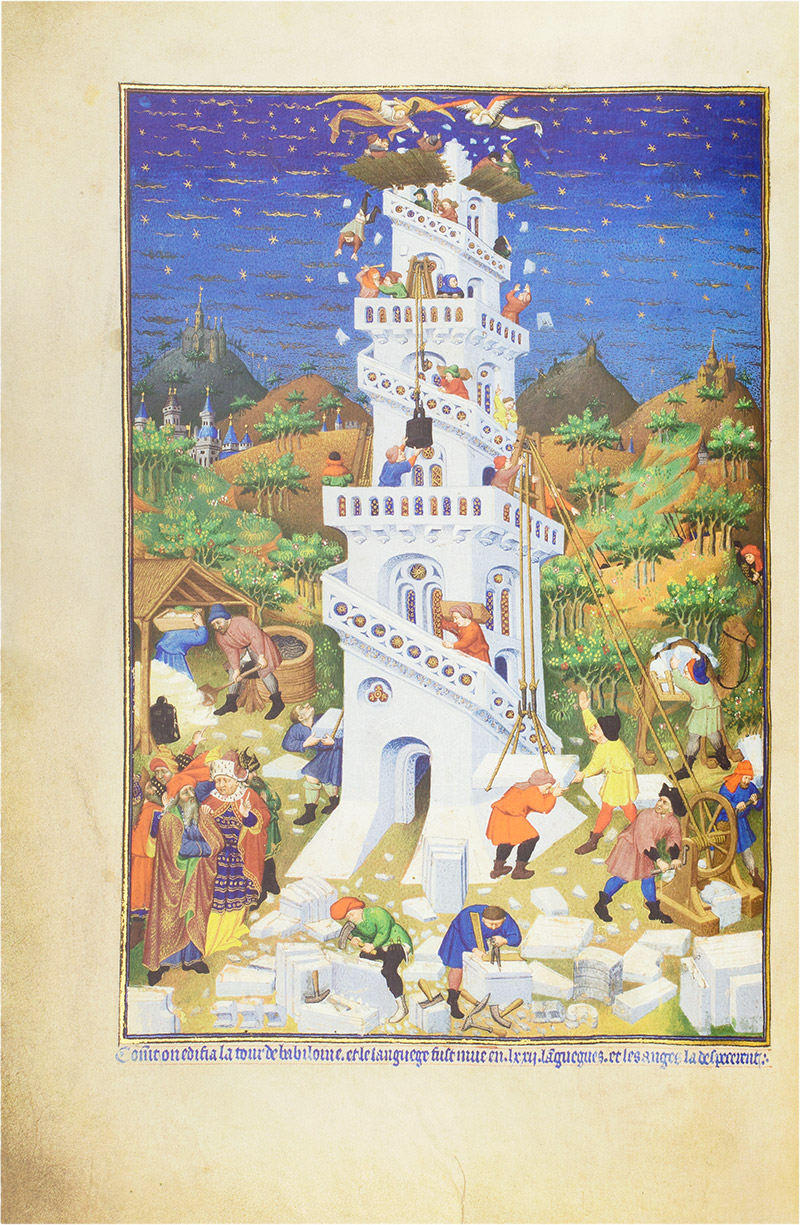

In addition to the 300+ lovely manuscripts he collected, Jean de Berry also commissioned four magnificent books of hours from the best French and Flemish workshops: Les Petites Heures-, Les Grandes Heures-, Le Belles Heures-, and Le Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. All of them are ranked among the finest examples of medieval illumination, but the Très Riches stands out as a true milestone due to the refinement of its décor and the great masters who created it: the Limbourg Brothers, Barthélemy d’Eyck, and Jean de Colombe.

Gothic Books of Hours

To the facsimile

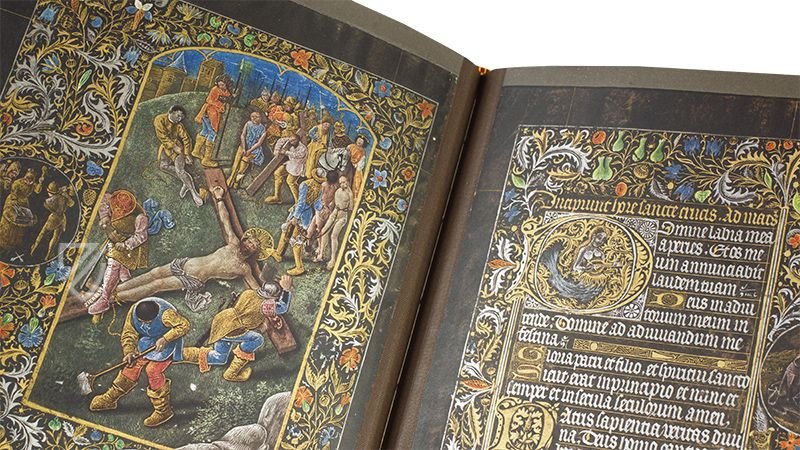

The golden age of French illumination coincided with the ascension of the book of hours as the most popular type of manuscript, and as a result, French, especially Parisian workshops, were producing many of the finest examples of this genre during the Gothic period. Some of the great masters of this period include Jacquemart de Hesdin, Jean le Noir, and the Bedford Master, whose Parisian workshop created the Bedford Hours, considered by many worldwide to be the richest and most beautiful illuminated manuscript of medieval book art. This fact is all the more incredible because the true identity of the Bedford Master has eluded art historians thus far, all they know is his name of convenience and that he lived in Paris from 1405 to 1465. Nonetheless, the workshop of the Bedford Master was the equal of any that came before or after it.

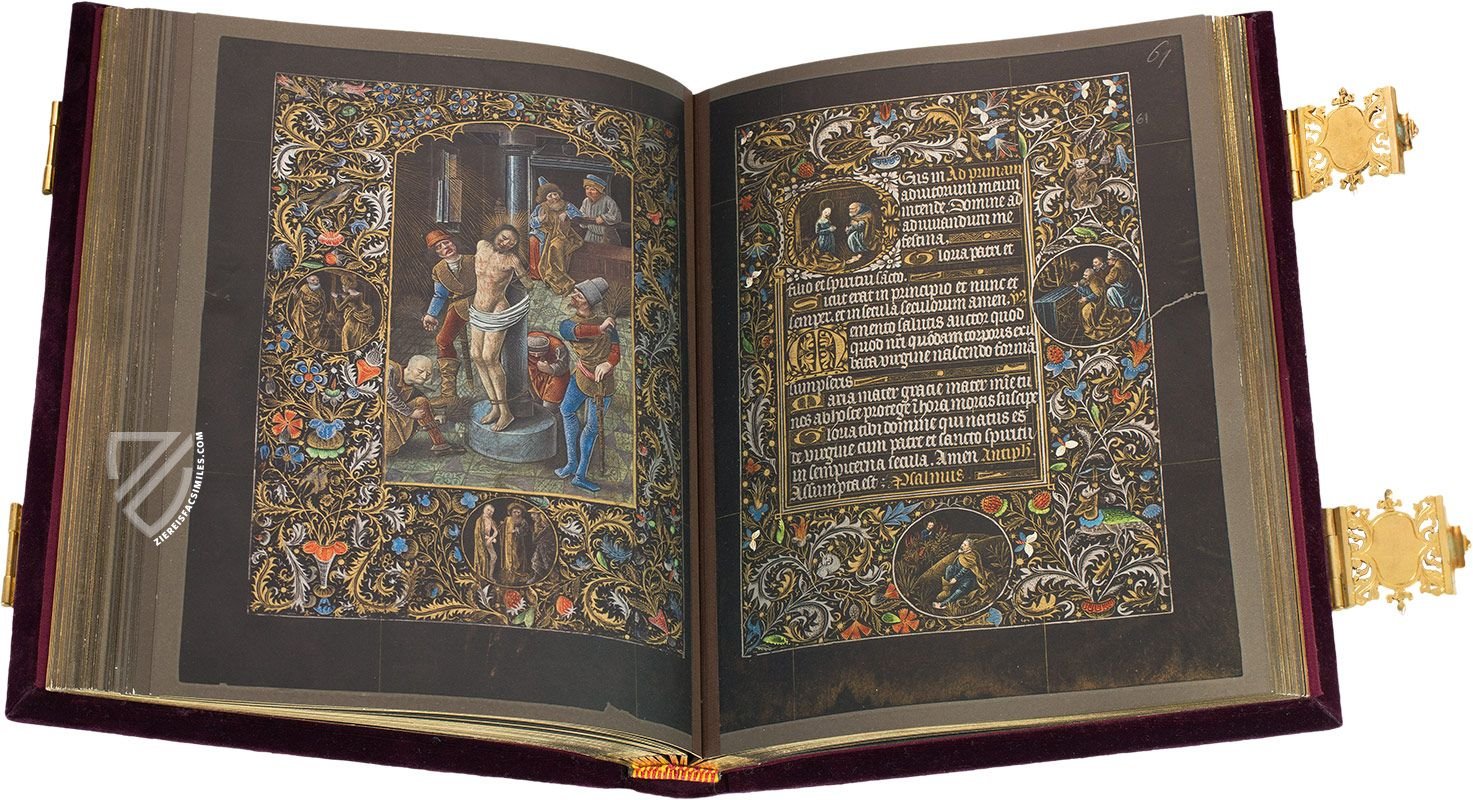

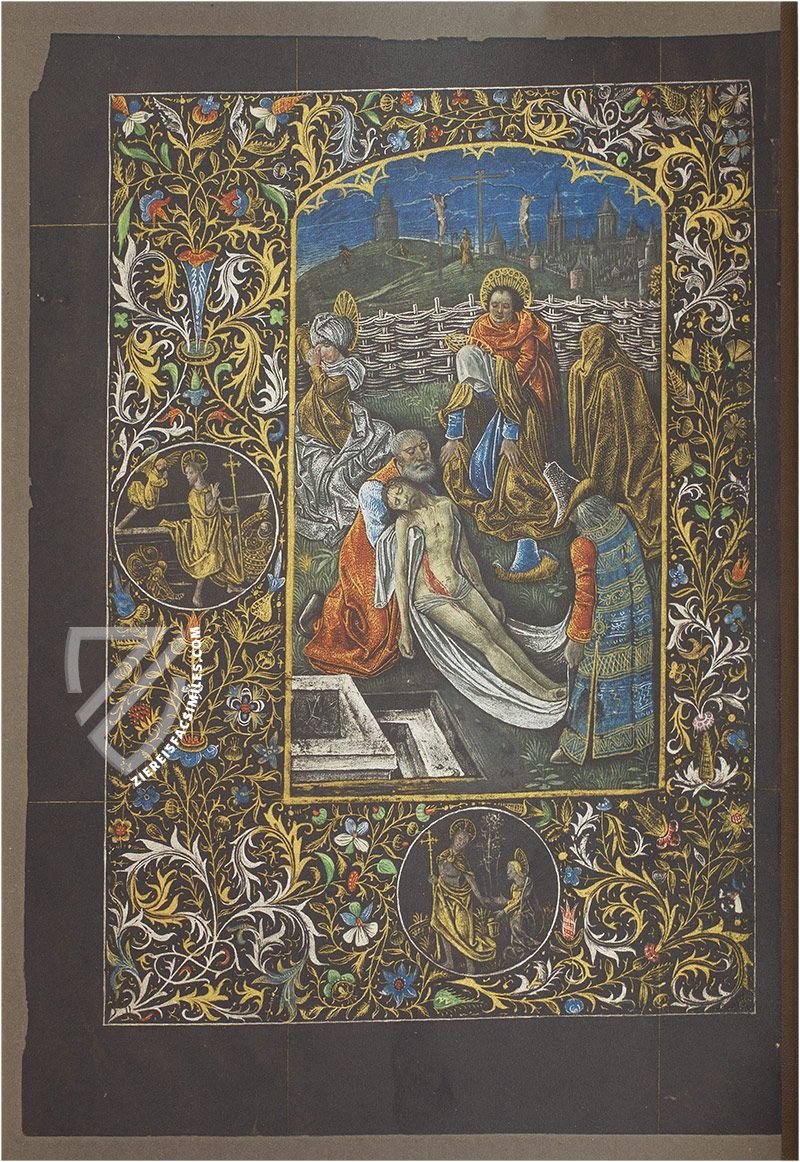

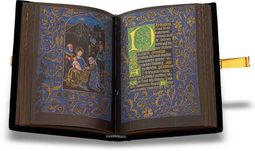

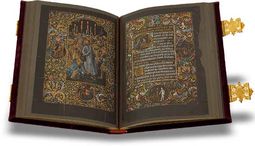

Black Hours

In spite of the rather ominous moniker, the term “black hours” does not have any kind of evil connotation, but referred instead to some of the most unique and spectacular manuscripts of the entire Middle Ages: a series of books of hours made with black-dyed parchment. Using an iron-copper oxide solution, the vellum was dyed black, making it possible for the illuminators to employ a color scheme that took advantage of the reverse contrast to the typical dark text and imagery against a light background. Instead, they were able to make use of bright pastel colors that contrasted against the dark background. The text of these manuscripts is equally impressive because it is written entirely in gold and silver ink.

These manuscripts were made in Bruges ca. 1450-1475 during the reigns of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold for some very sophisticated members of the ducal court of Burgundy, which had come to rival the French royal court, both in terms of power as well as magnificence. During the 15th century, the Duke of Burgundy was also the sovereign of Flanders, the center of the European textile trade and home to some of the best ateliers in Europe, Bruges in particular.

Unfortunately, the solution for dying the pages is ultimately corrosive, and as a result, only seven specimens of these precious works of art survive today. Only three are still bound as codices while the rest are preserved as single folios between glass plates. This tragic fragility only adds to the allure of their artistry, and facsimiles of these delicate treasures have made researching them possible without further damaging the originals.

Italian Renaissance Books of Hours

To the facsimile

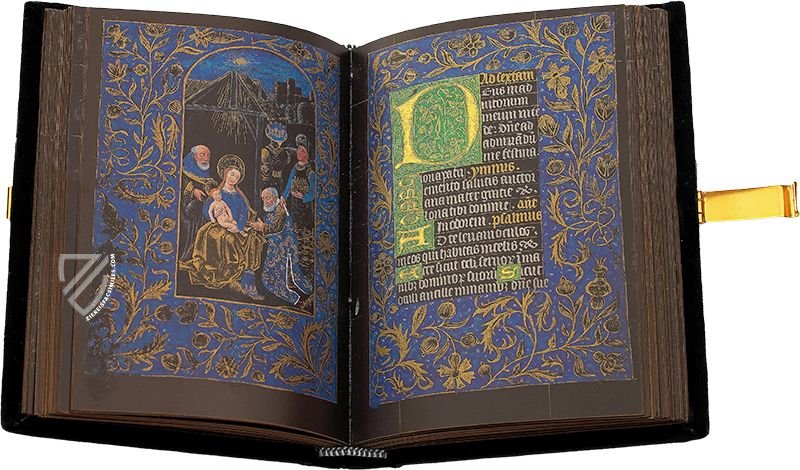

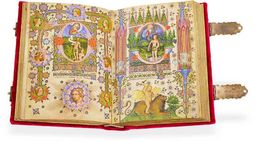

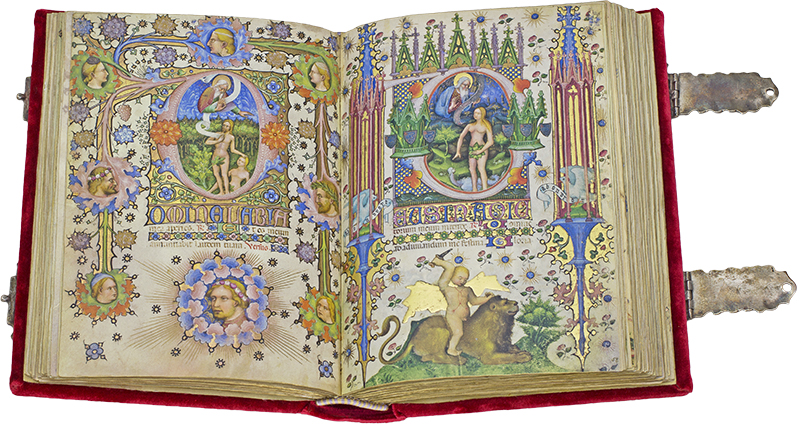

Meanwhile, south of the Alps, the Italian Renaissance had been in full-swing for some time, and the artistic style of the Italian books of hours from this period reflects contemporary innovations. The most beautiful examples of this splendor are also associated with some of the greatest names of the Italian Renaissance, including the powerful Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan and Lorenzo de’ Medici “the Magnificent”, who earned the epithet through his generous patronage of the arts. Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who ruled as Duke of Milan from 1351 to 1402, was arguably the richest prince of his day and an unparalleled patron of education and the arts.

The two-volume Visconti Book of Hours was made between 1390 and 1428 and is considered to be the greatest Italian contribution to the genre – the first volume was designed by Giovanni de’ Grassi and the second by Belbello da Pavia. Its simple velvet binding does not prepare the beholder for the rich cornucopia of decoration within. That being said, this magnificent manuscript is not without its rivals.

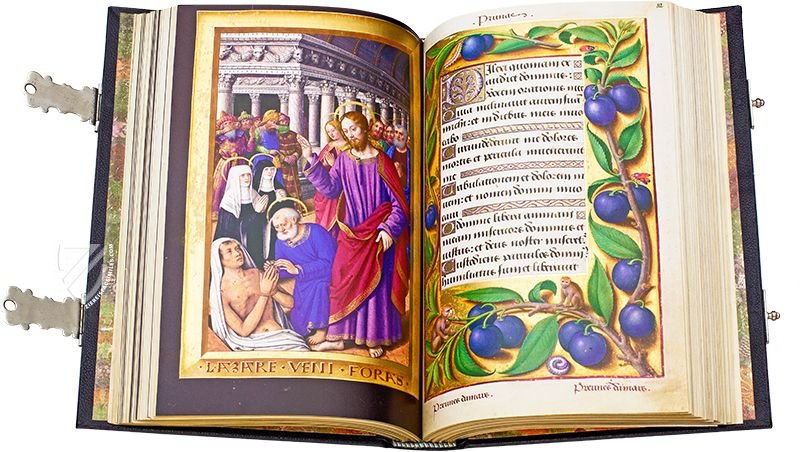

During the 1480’s, Lorenzo de’ Medici commissioned an incredible book of hours as a wedding present for each of his three daughters, two of which were made by Francesco Roselli and the other by the workshop of Mariano del Buono. All feature luxurious velvet bindings with gold claps and fittings – one bejeweled while the other two feature enamel miniatures – and the refinement and detail of illumination that one would expect of Renaissance Italy. These miniatures are presented in incredibly detailed frames and marginal decorations that almost rival the central images both with regard to the importance of their artistic content and because they vie with the miniatures for space on the page.

Finally, these Italian books of hours are distinguished by the skill of the scribes responsible for the text, which is presented so clearly and uniformly that one could be forgiven for wondering if they were printed instead of written by hand.

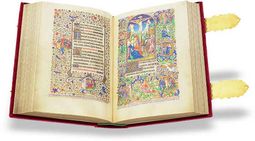

Effects of the Printing Press

Although Gutenberg’s invention resulted in a dramatic downturn in the numbers of manuscript books of hours being produced, demand from royalty and other high-ranking members of society continued into the 16th century so that the high end of production for books of hours continued. Les Grandes Heures d’Anne de Bretagne is one of the last great masterpieces of French illumination. Made in the workshop of Jean Bourdichon, one of France’s greatest illuminators, between 1503 and 1508, the manuscript is distinctive for its full-page miniatures reminiscent of panel paintings, as well as the depiction of 330+ plants with their scientific names, making it both a book of hours and a botanical encyclopedia.

Although incredible books of hours continued to be produced in France and Italy, Flanders and Bruges in particular emerged as the leader of manuscript production during the second half of the 15th century, and it was here that the styles of the Italian Renaissance and northern Gothic were blended into incredibly sophisticated works of art like the Le Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry that would inspire the Old Dutch Masters of the 17th century. So, although the number of manuscripts being reduced declined, the expensive nature of the remaining commissions funded continued artistic development.

The Final Flowering

To the facsimile

Jean de Colombe created the spectacular Book of Hours of Luis de Laval ca. 1489 after almost a decade of work for the influential commissioner of the same name who served King Louis IX of France. It contains an incredible 1,234 miniatures, including 157 full-page miniatures that distinguish themselves through their incredible landscapes, spatiality, and generous application of gold. Such a work of art would be the possession of French royalty for generations to come.

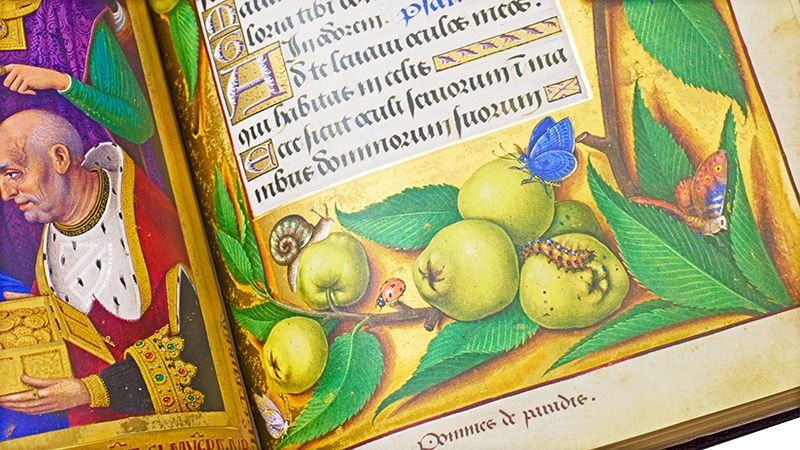

One of the last and most refined manuscript books of hours was Simon Bening's Flowers Book of Hours, made between 1520 and 1525. As its name suggests, its decorative patterns contain flowers and buds of every kind, in addition to insects and small birds that are depicted with incredible realism and plasticity – every page of the manuscript is illuminated. Born the son of the great miniaturist Alexander Bening ca. 1483, Simon Bening also apprenticed with other great illuminators like Gerard Horenbout and had been recognized as “the best master of book illumination in all of Europe” by the time his famous book of hours was completed. His synthesis of styles and techniques from different artists, in addition to the plasticity and creativity of his own creations, culminated in one of the last and greatest treasures of medieval art.

Sunset of the Book of Hours

One reason why the emergence of book printing did not spell the immediate death of the manuscript is because there were already ateliers producing pre-made books of hours that had blank pages reserved for dedication pages and coats of arms. This trend continued with printed books, which would also sometimes leave spaces open for customized initials, or would have woodcuts that could be colored or left in black and white at the owner’s discretion. However, the popularity of the book of hours had irreversibly declined in Western Europe by the mid-16th century. Although official prayer books corresponding to the book of hours still exist in the Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox Churches, they are mostly simple modern codices that do not reflect the glory of their predecessors.