The 12th Century in Europe: Crusades, Power Struggles and the Decline of the Byzantine Empire

This is Part 8 of our Centuries series. In it, we will review the epic 12th century, beginning with the Crusader states in the Levant, the Second Crusade, and similar religious wars in central Europe and the Iberian Peninsula.

Then we turn to events in Italy and the Holy Roman Empire and the historic personality of Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa.

We will next examine the increasingly intertwined relationship between France and England during this time, and then return to the Levant for the Third Crusade.

Finally, we close out the century by examining events in the Byzantine Empire.

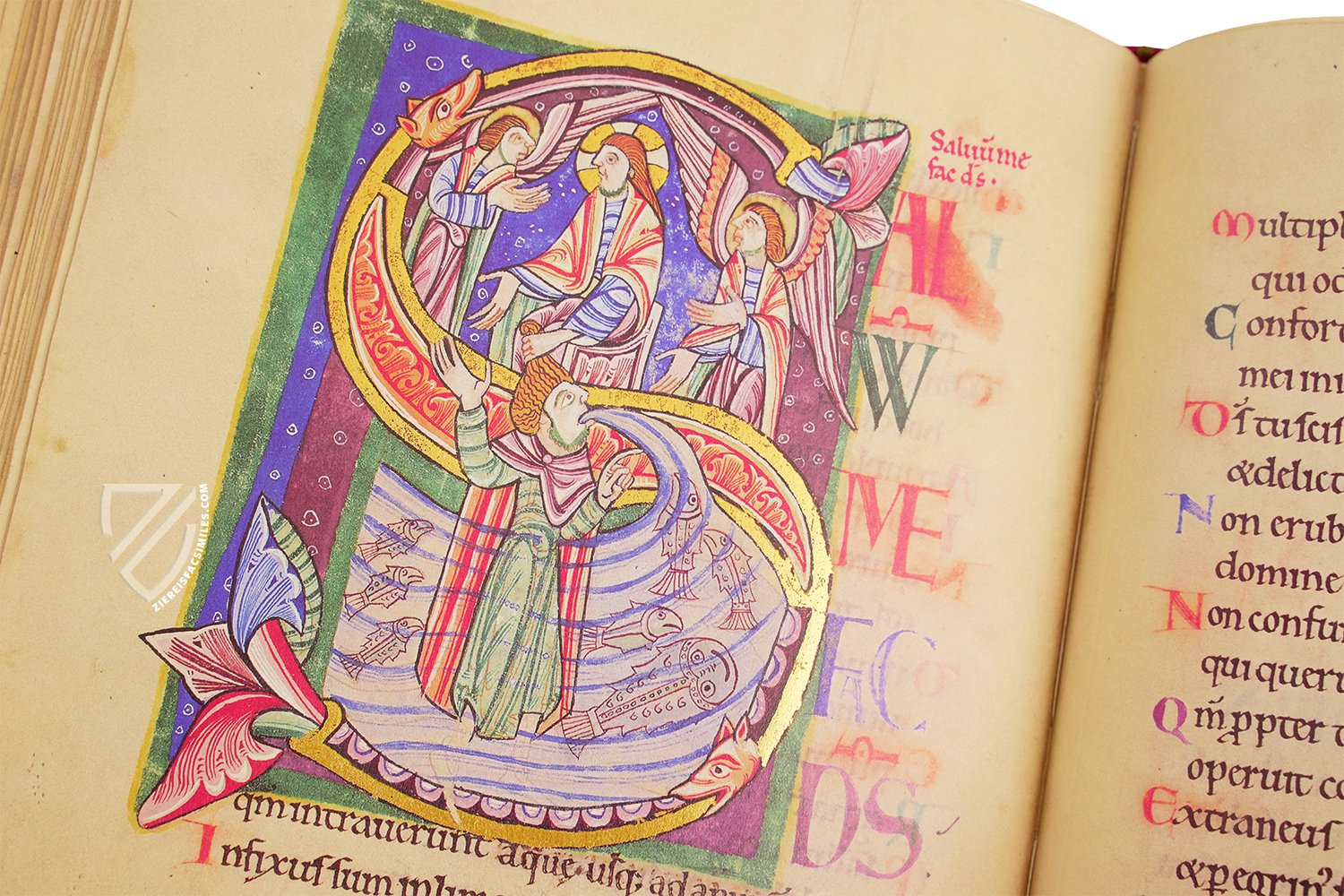

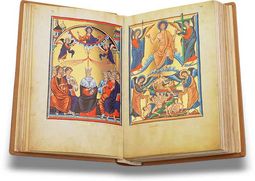

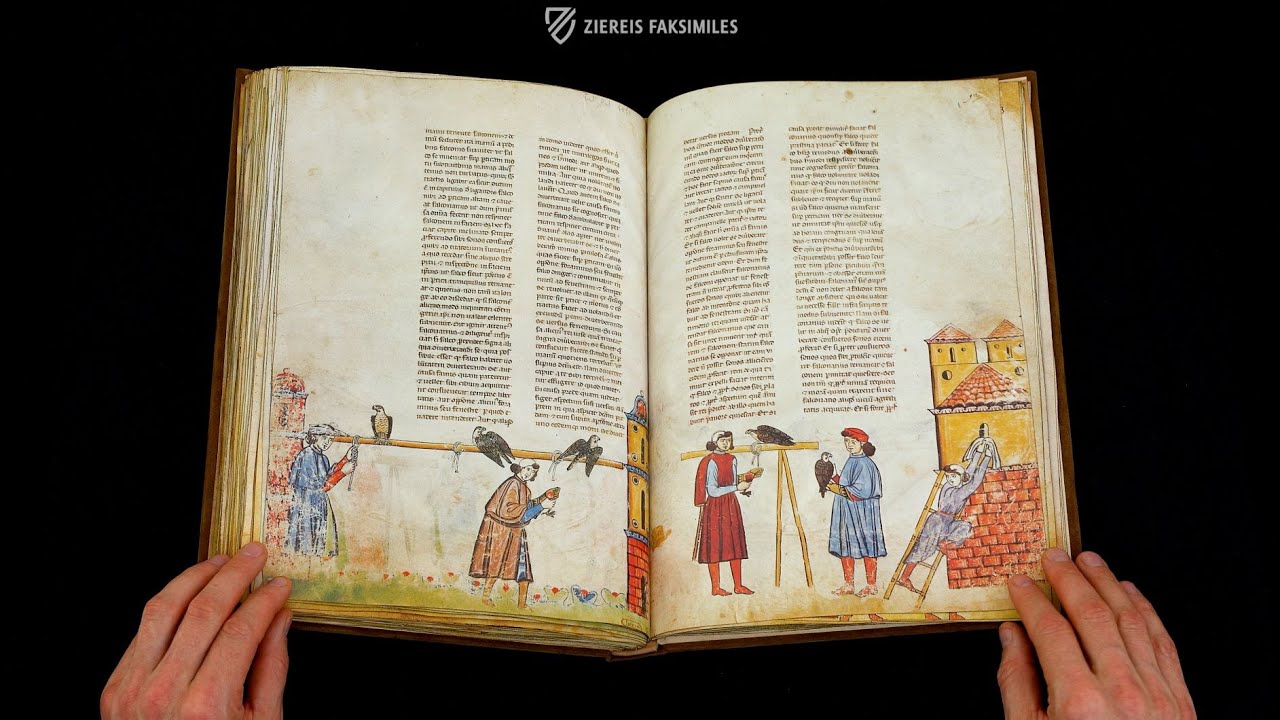

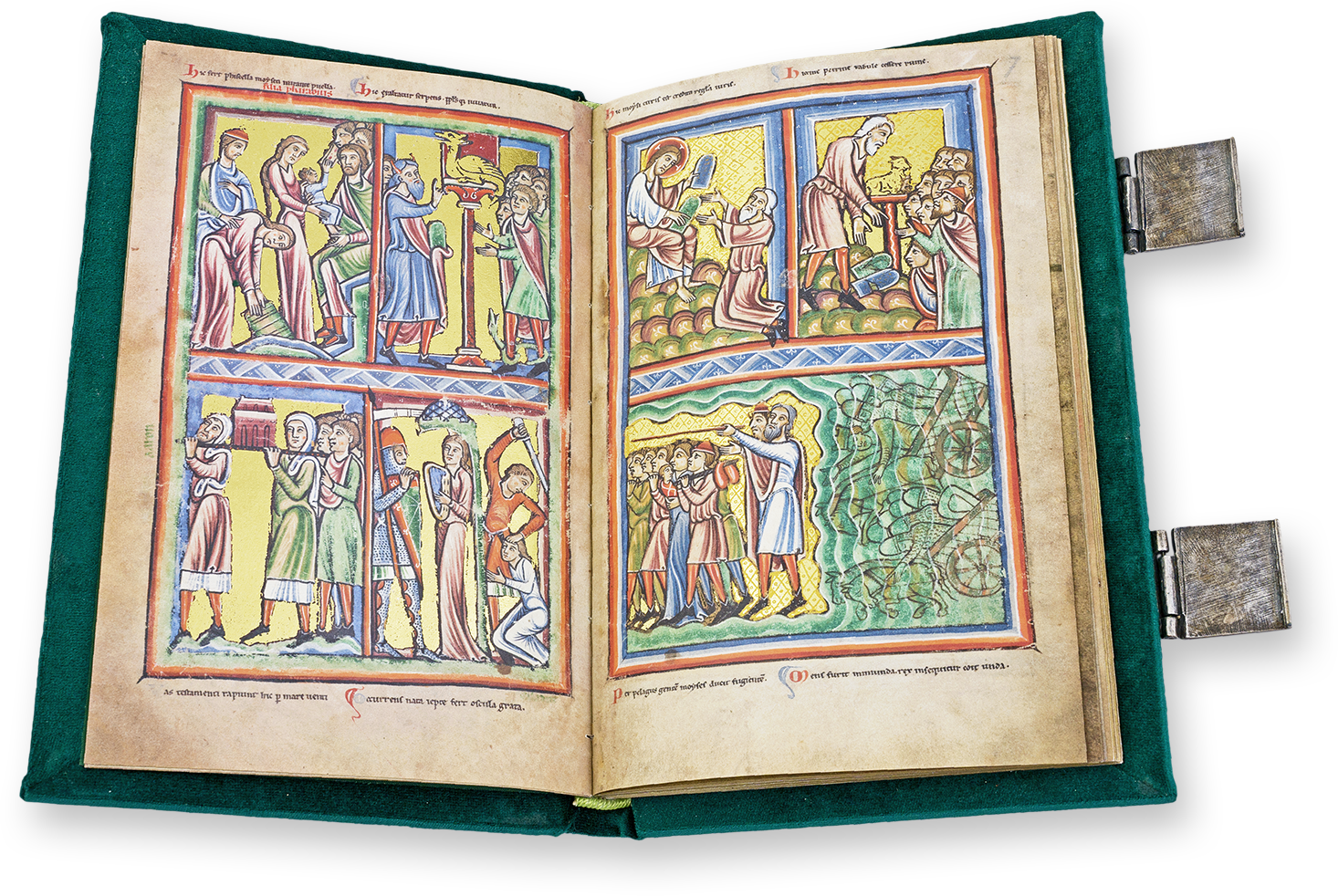

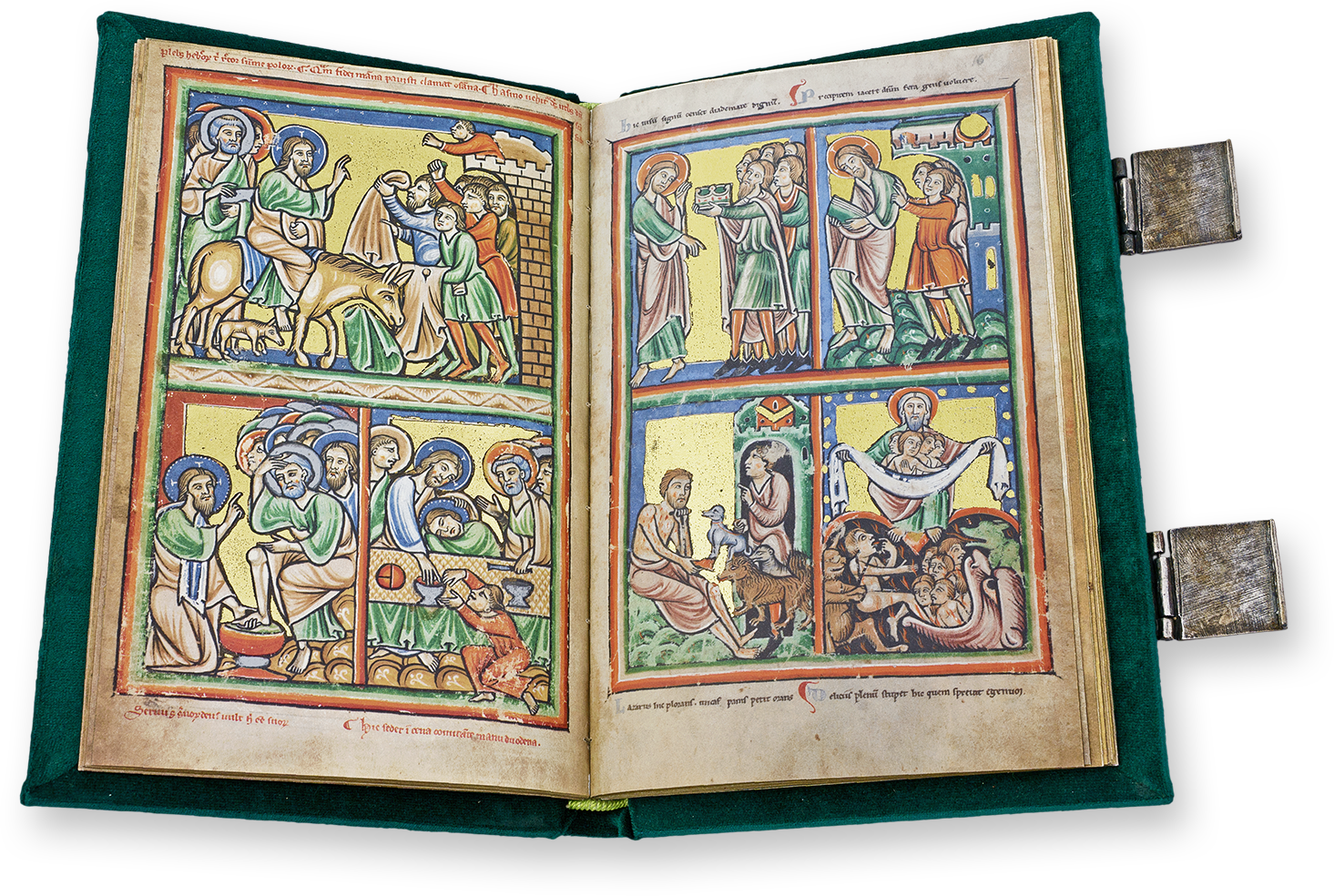

Demonstration of a Sample Page

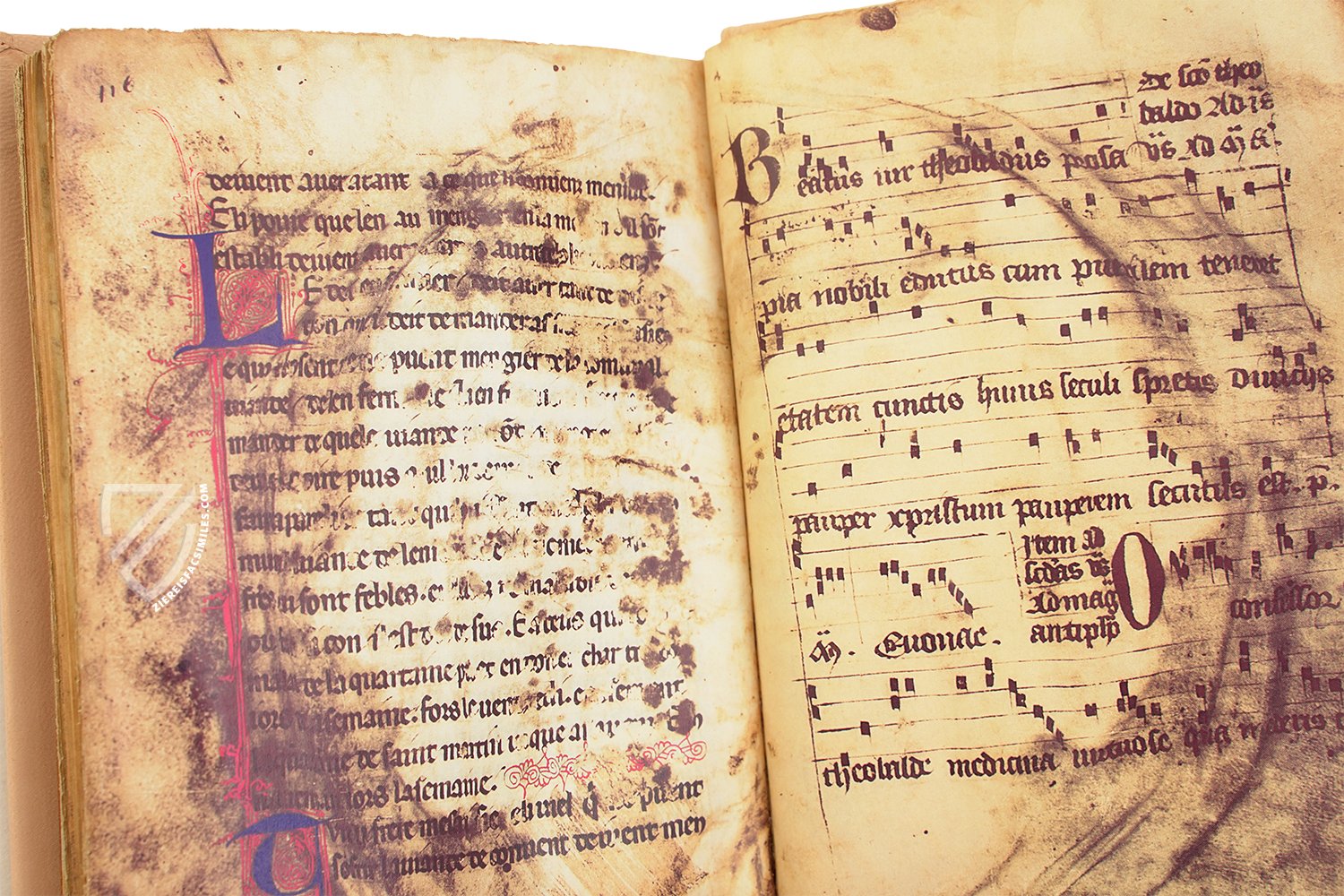

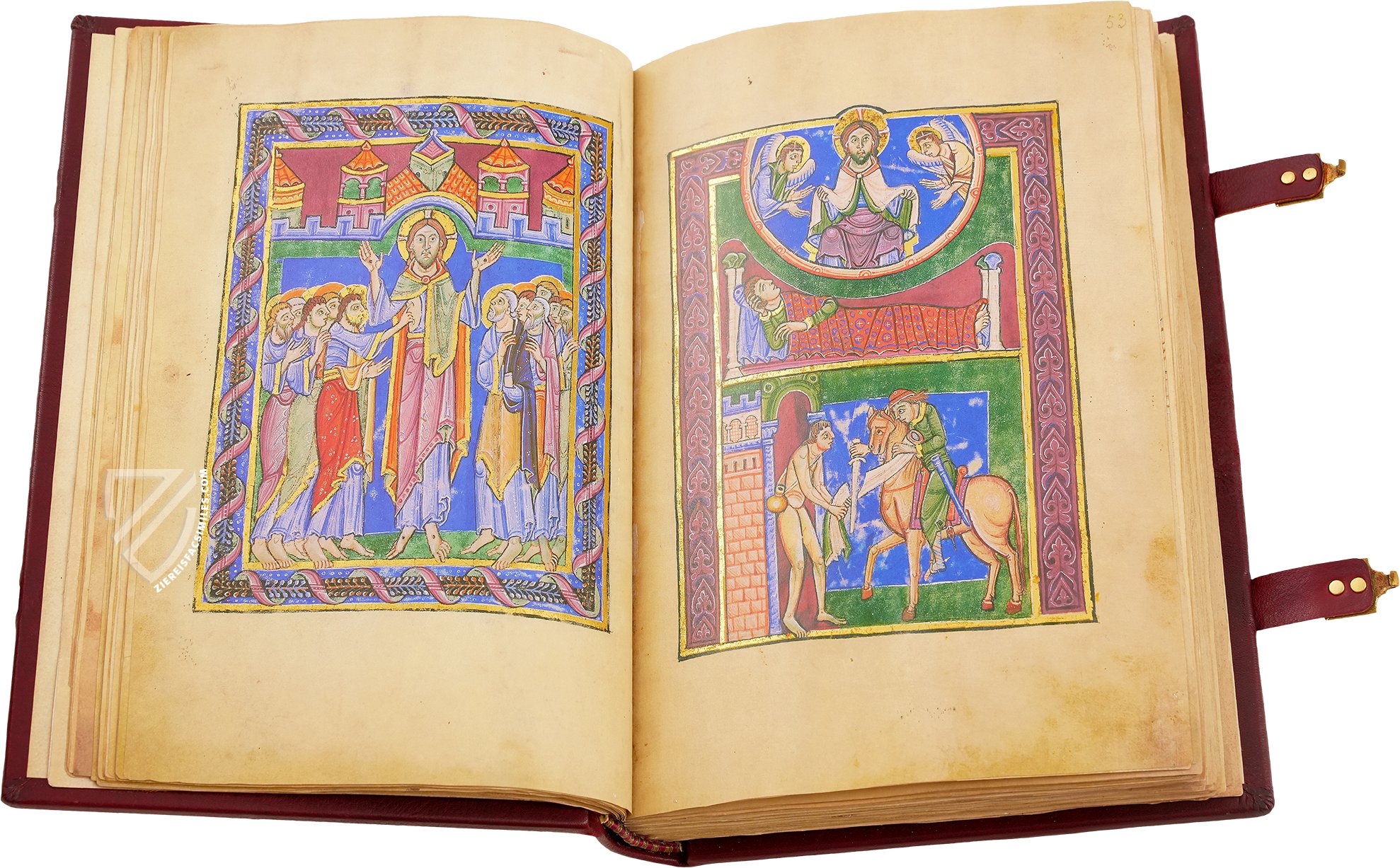

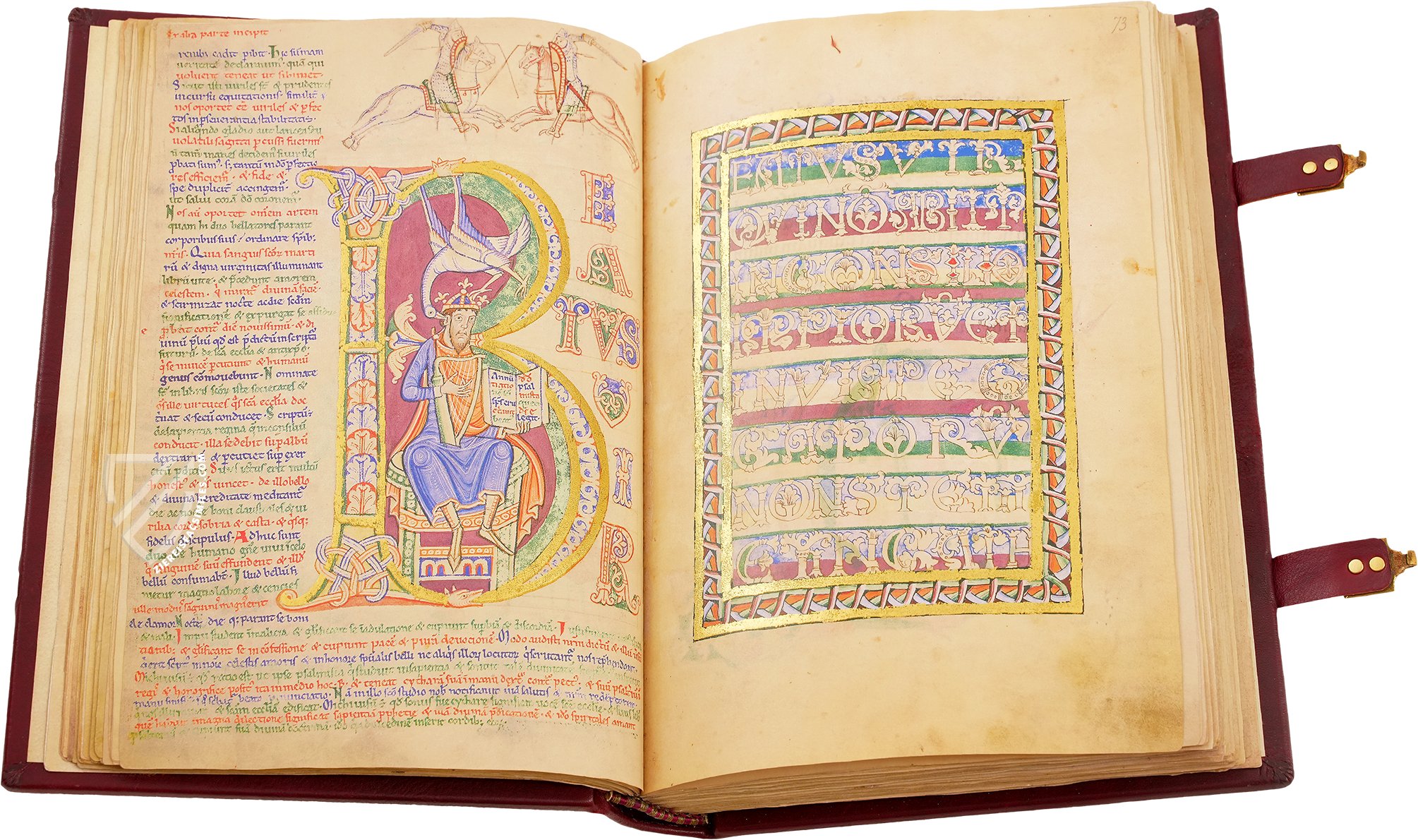

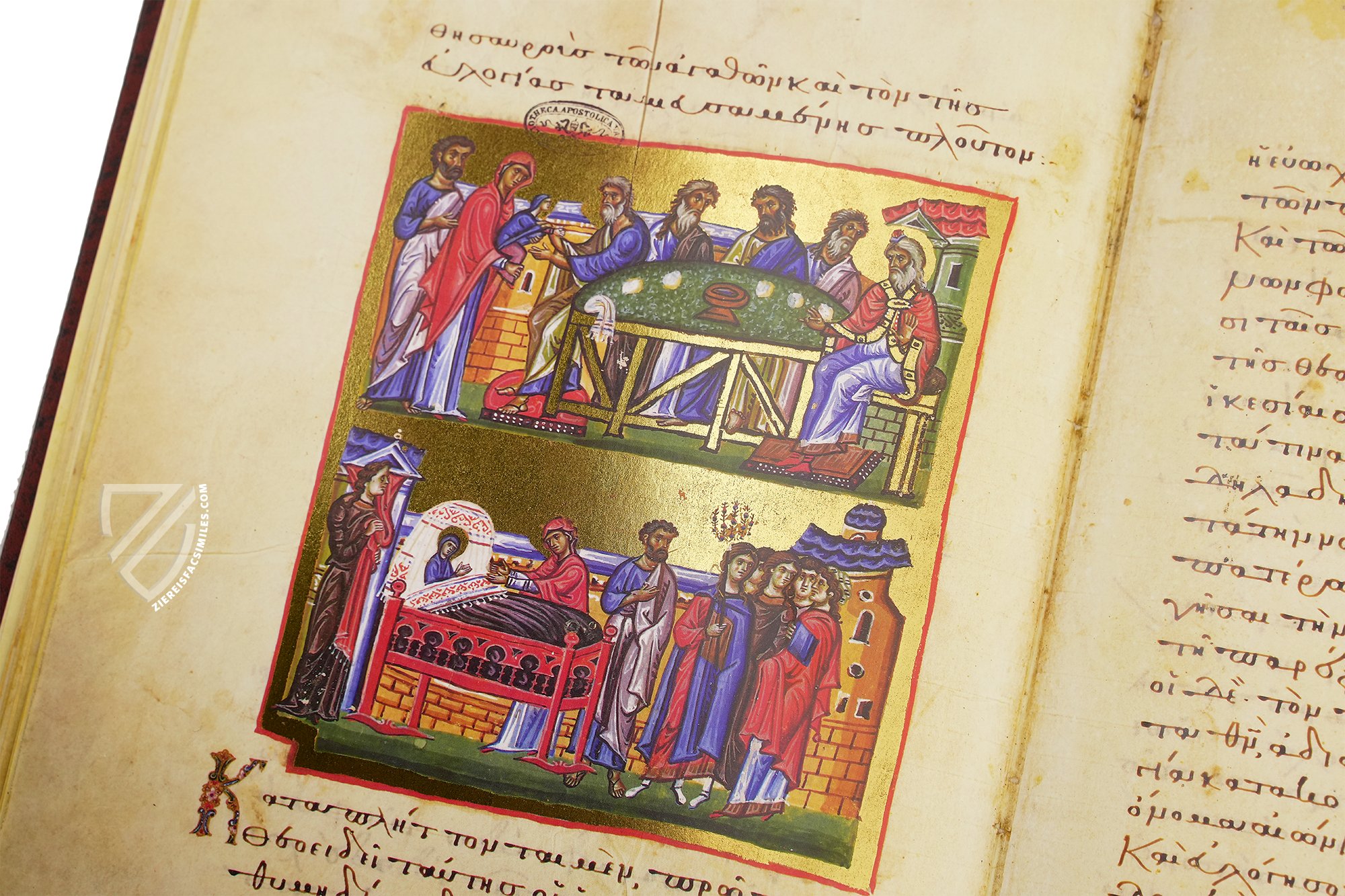

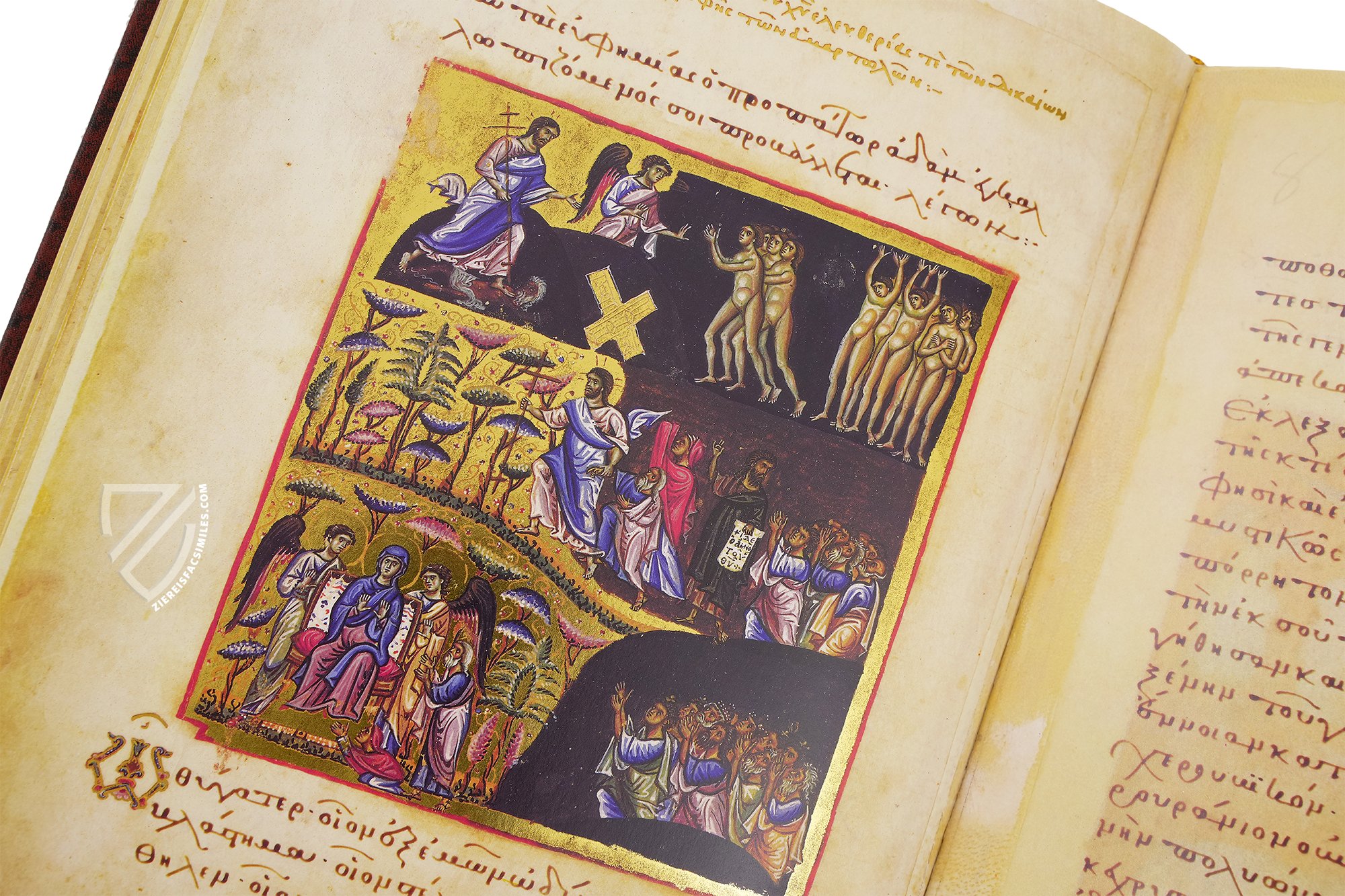

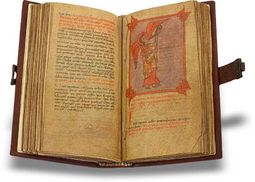

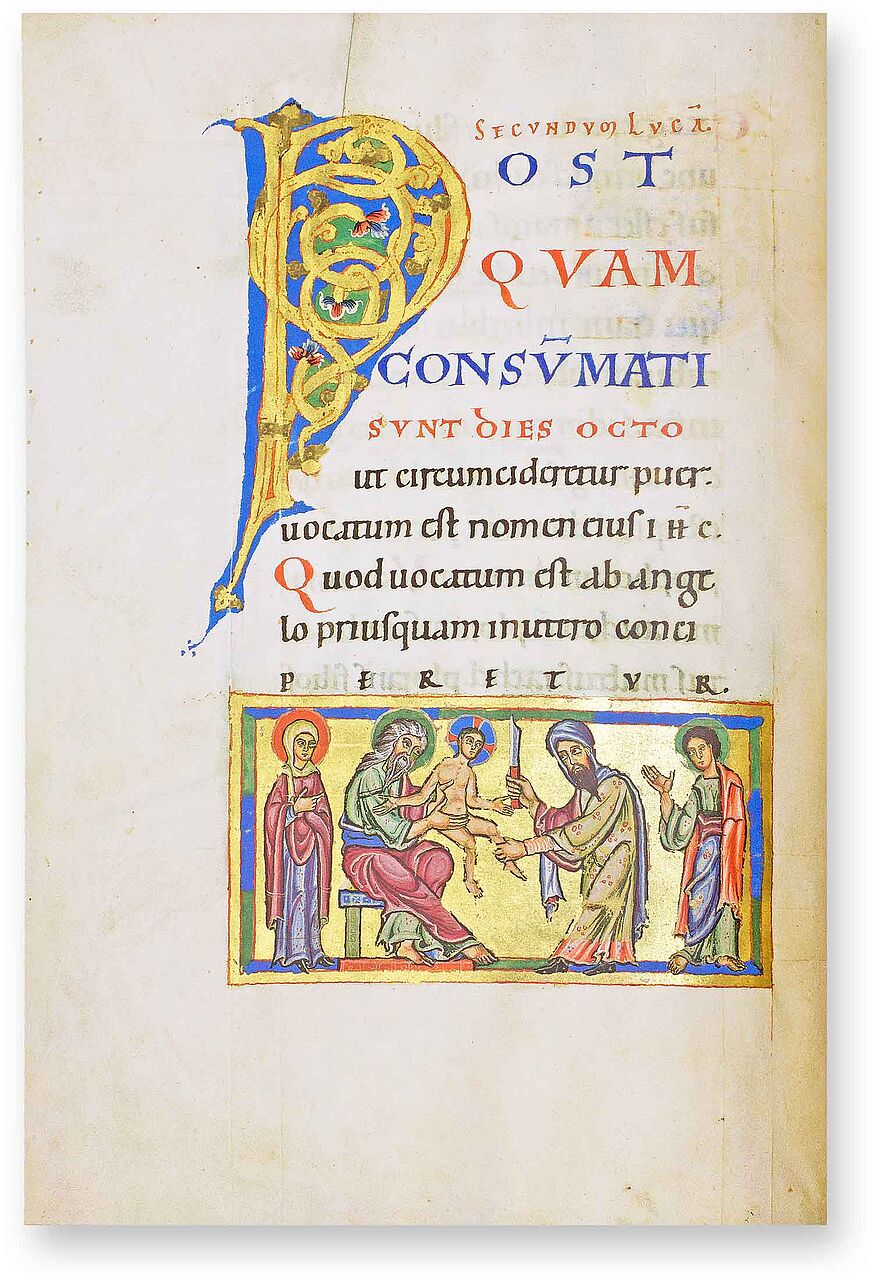

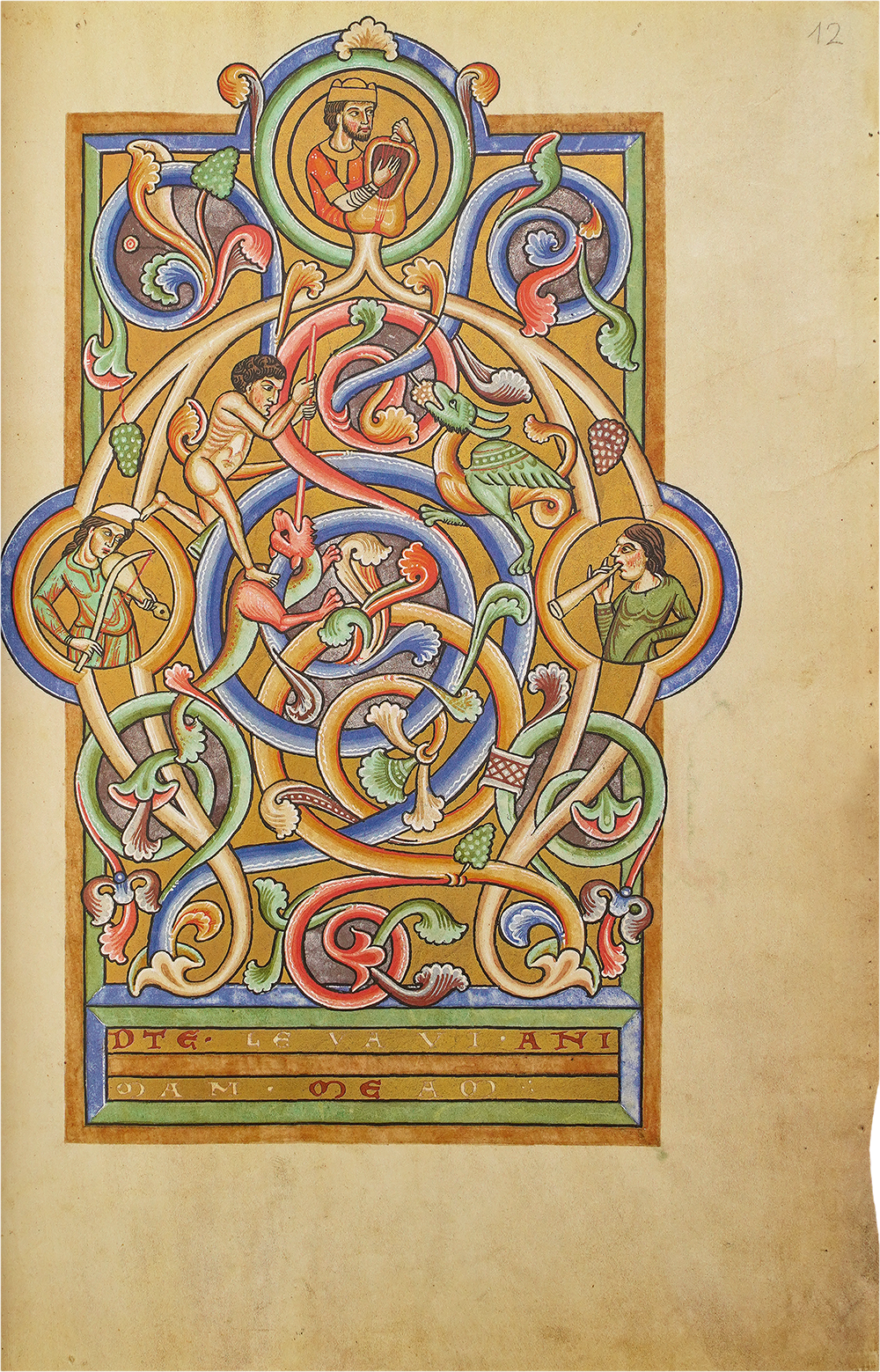

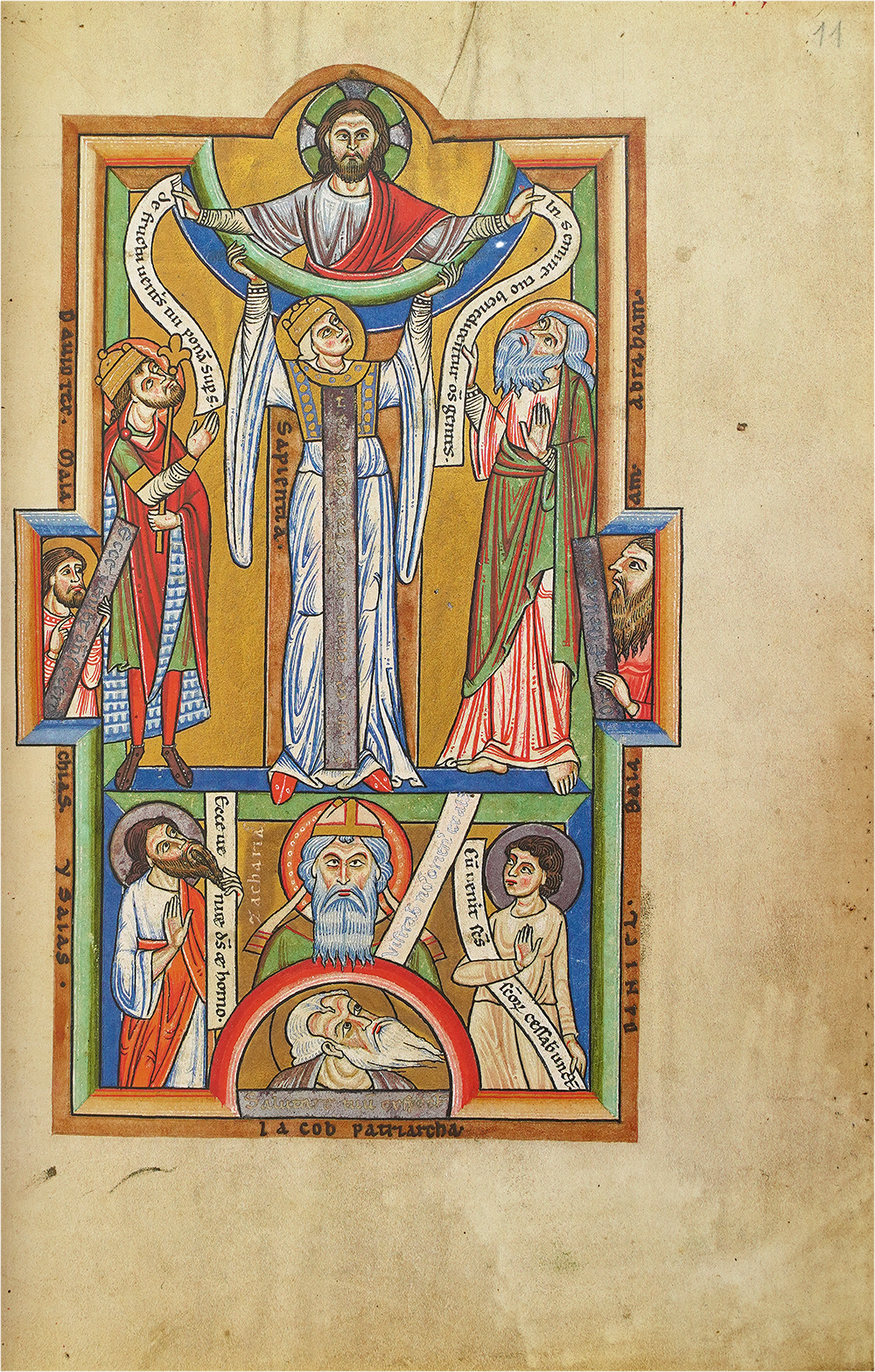

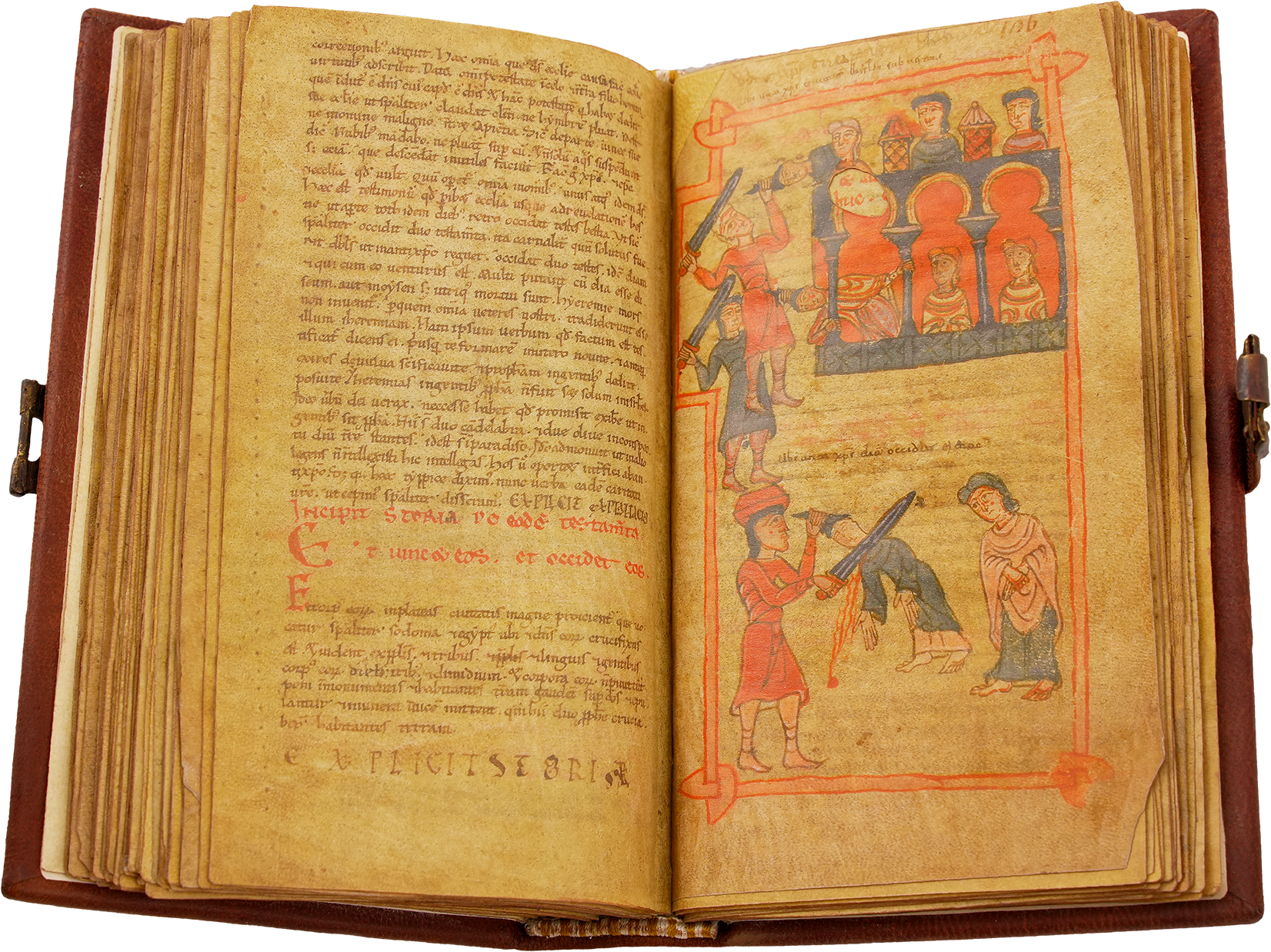

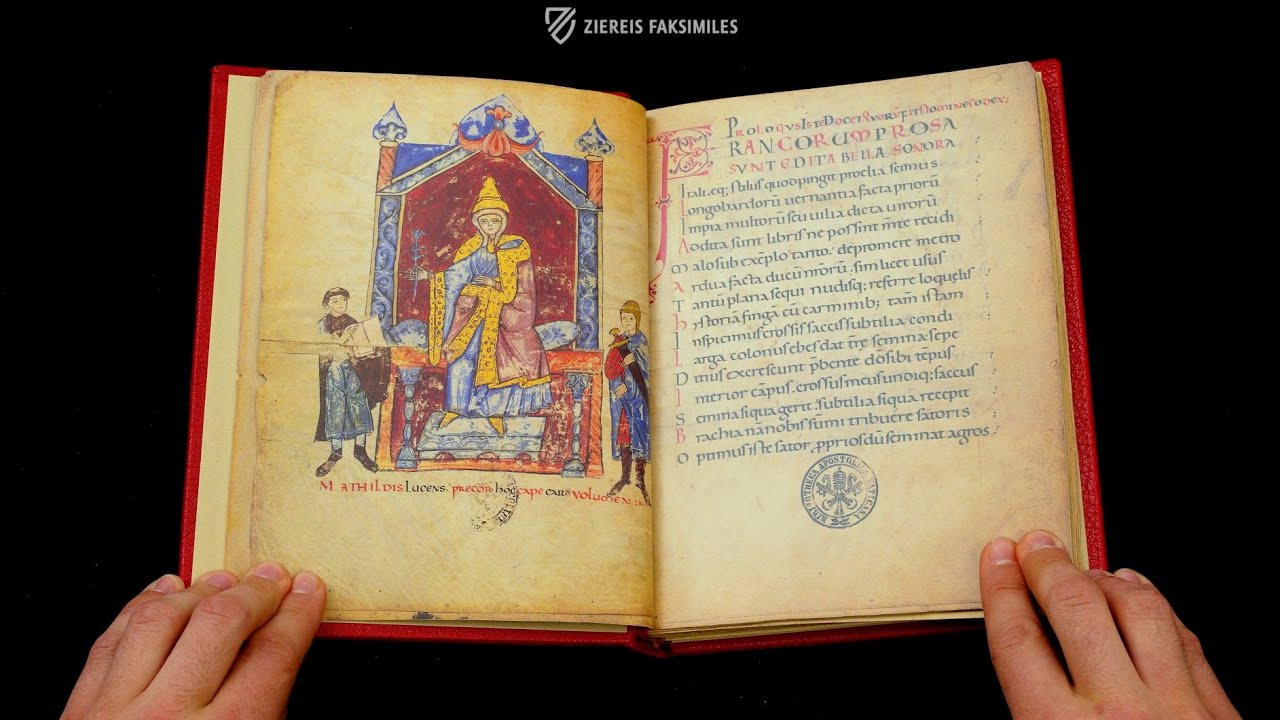

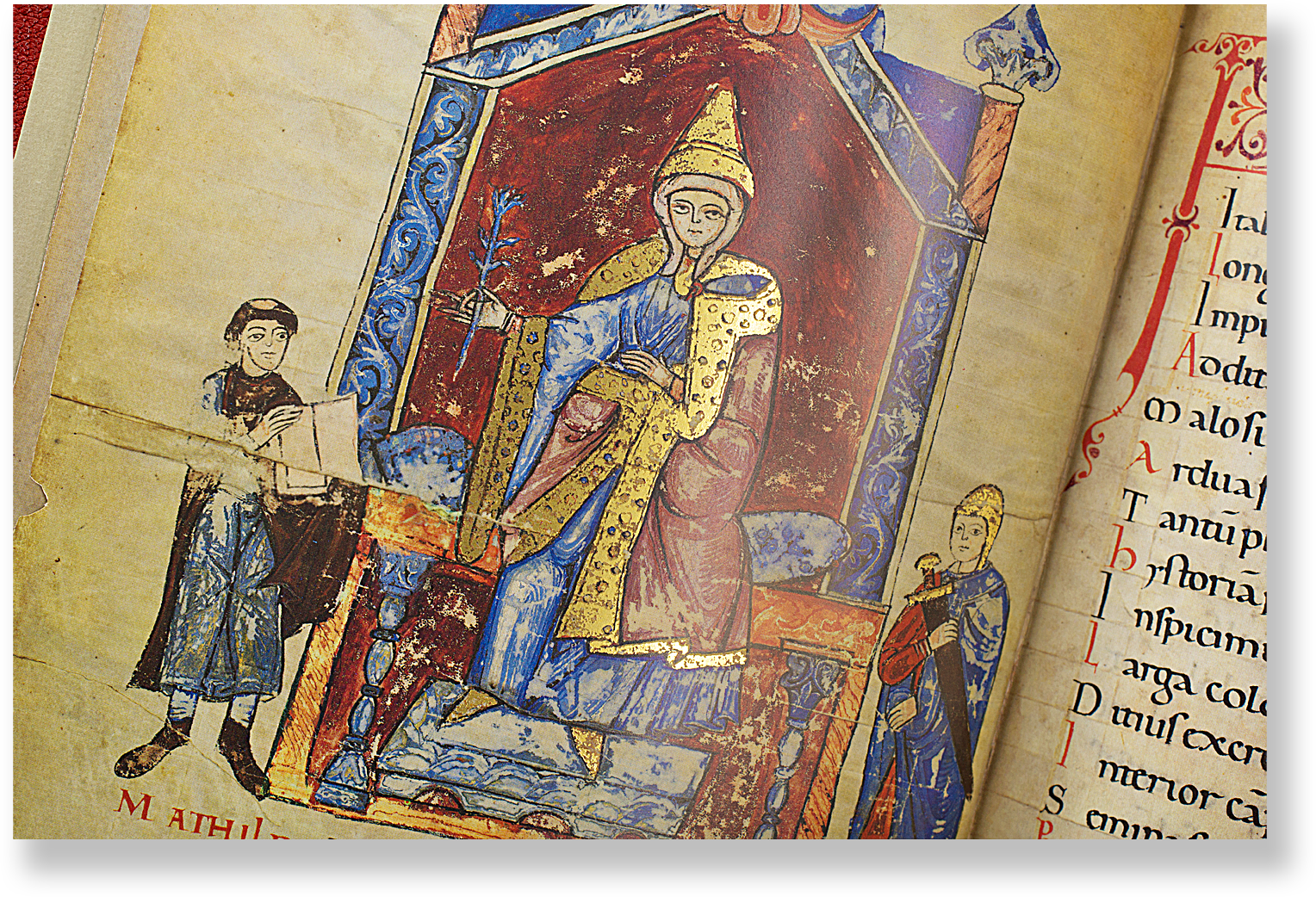

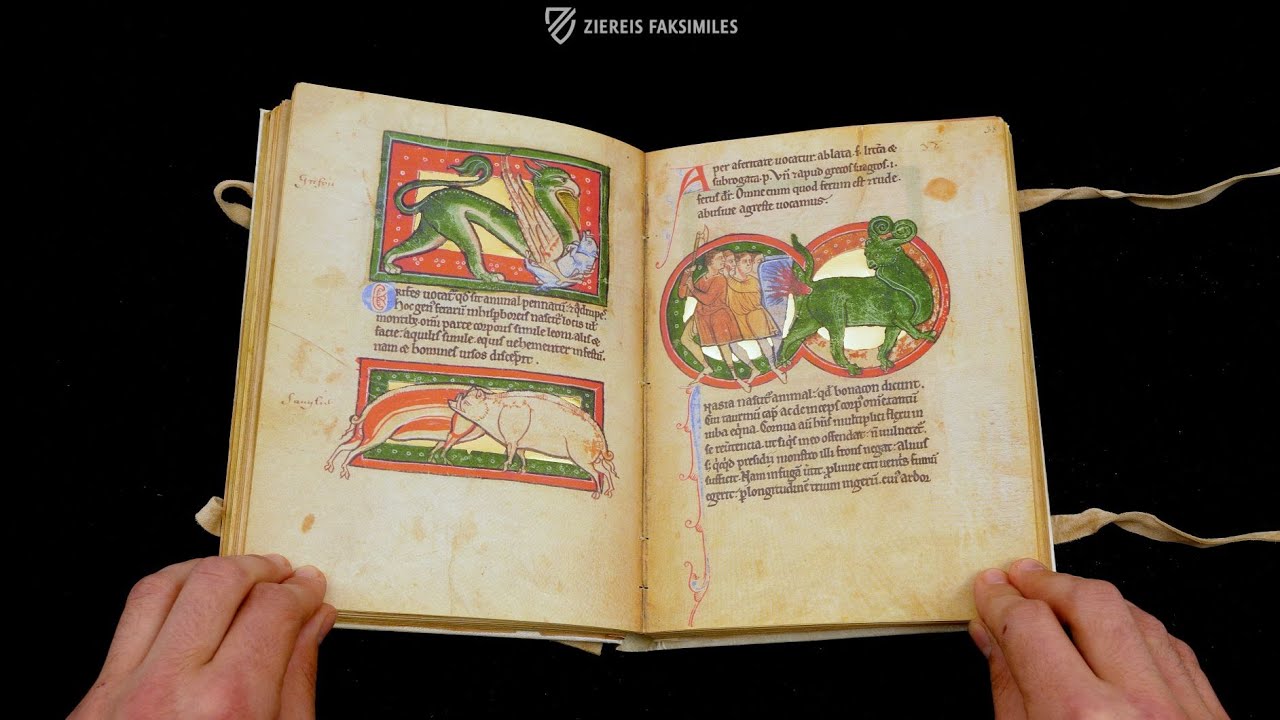

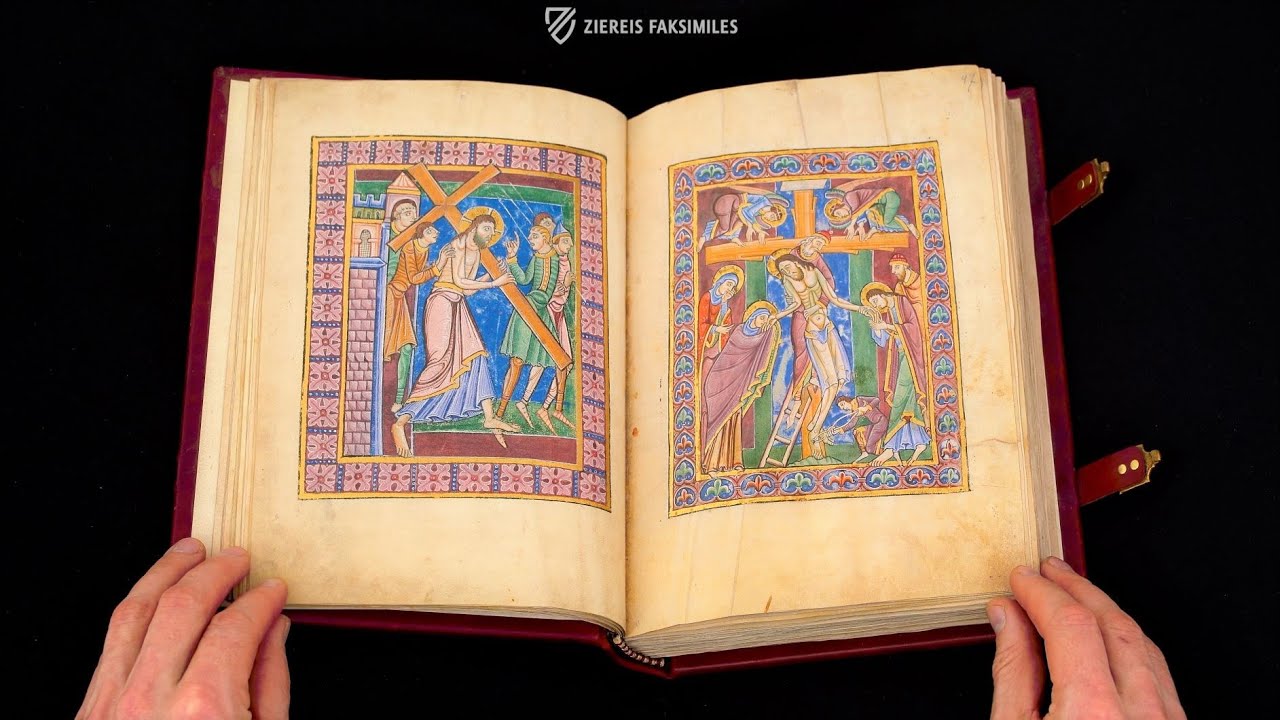

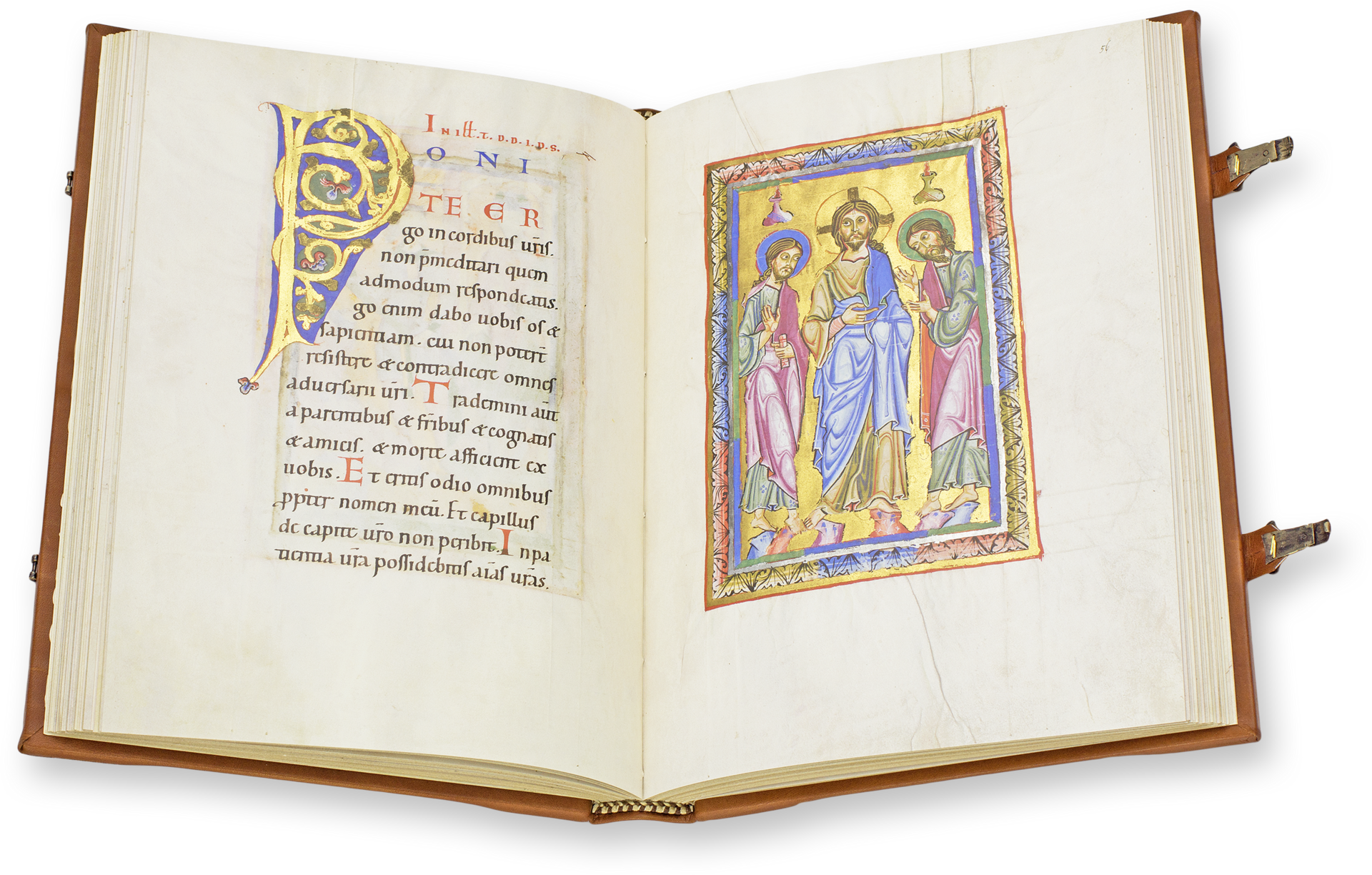

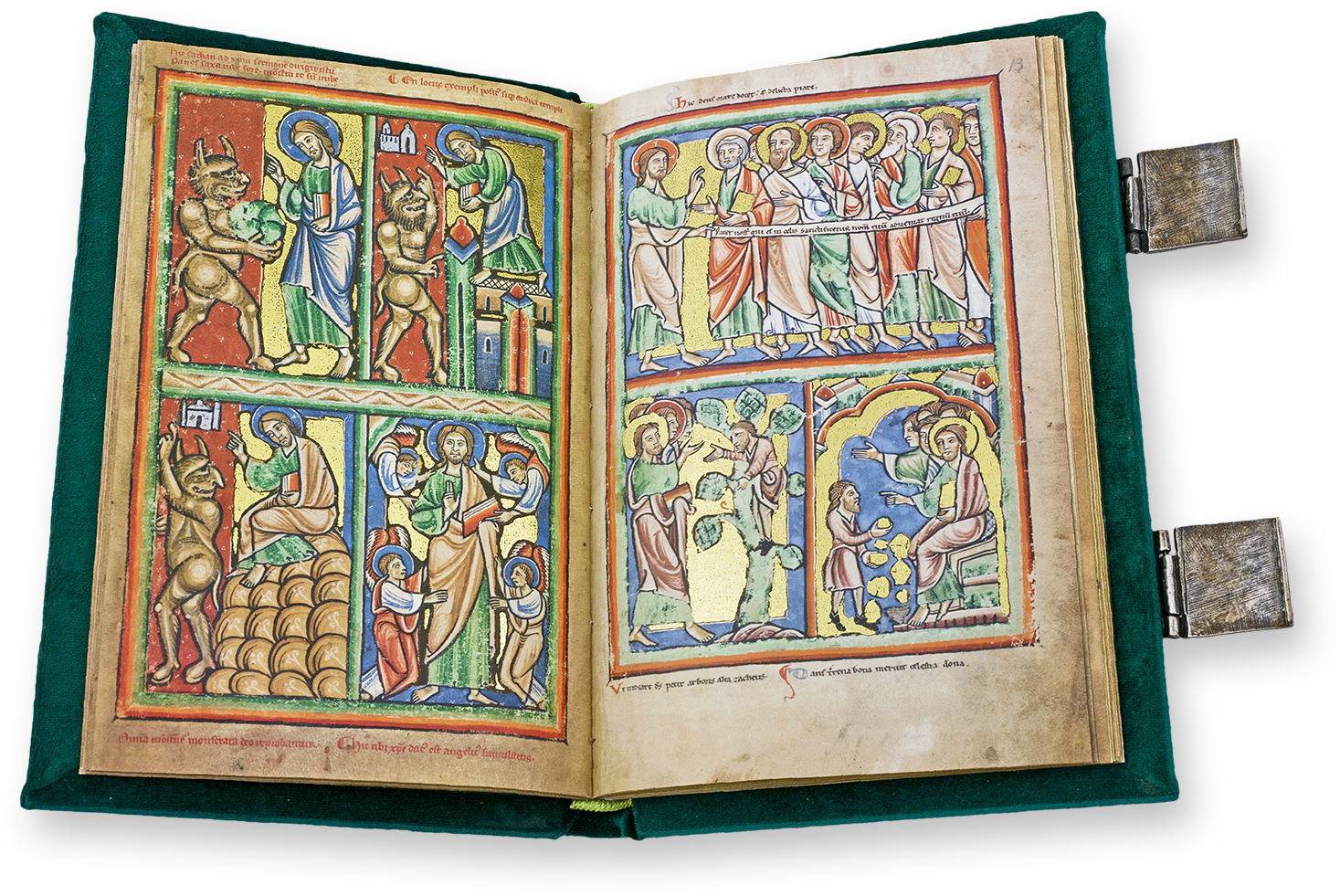

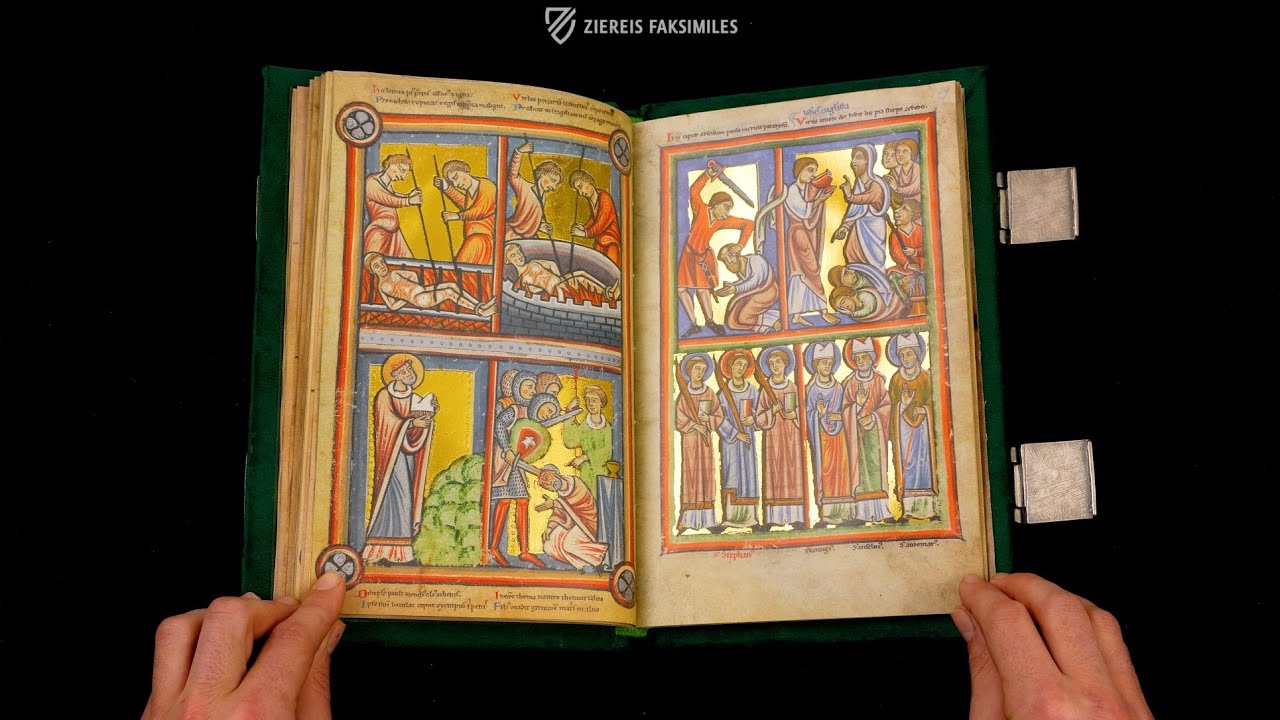

St. Peter Pericopes from St. Erentrud

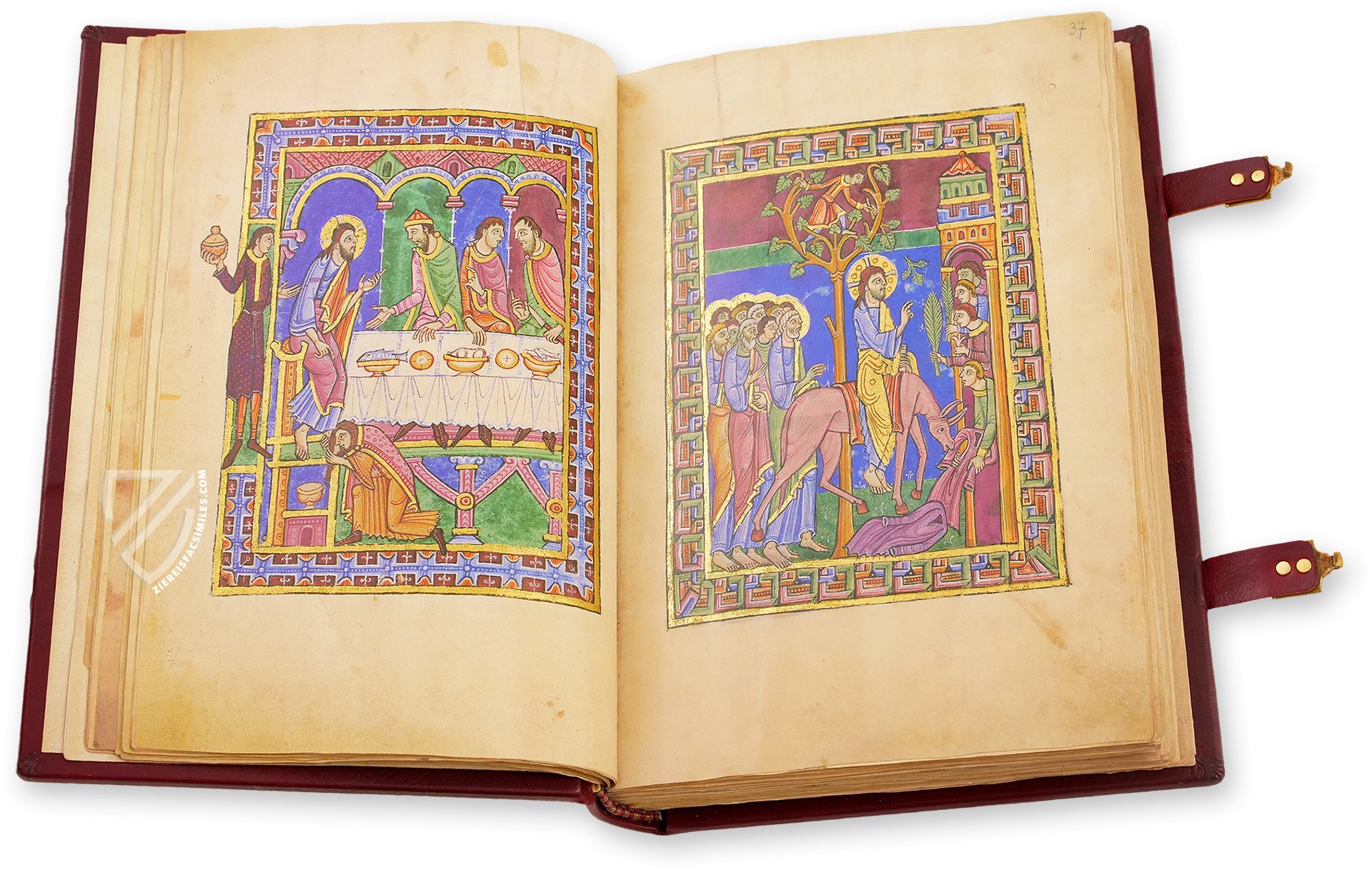

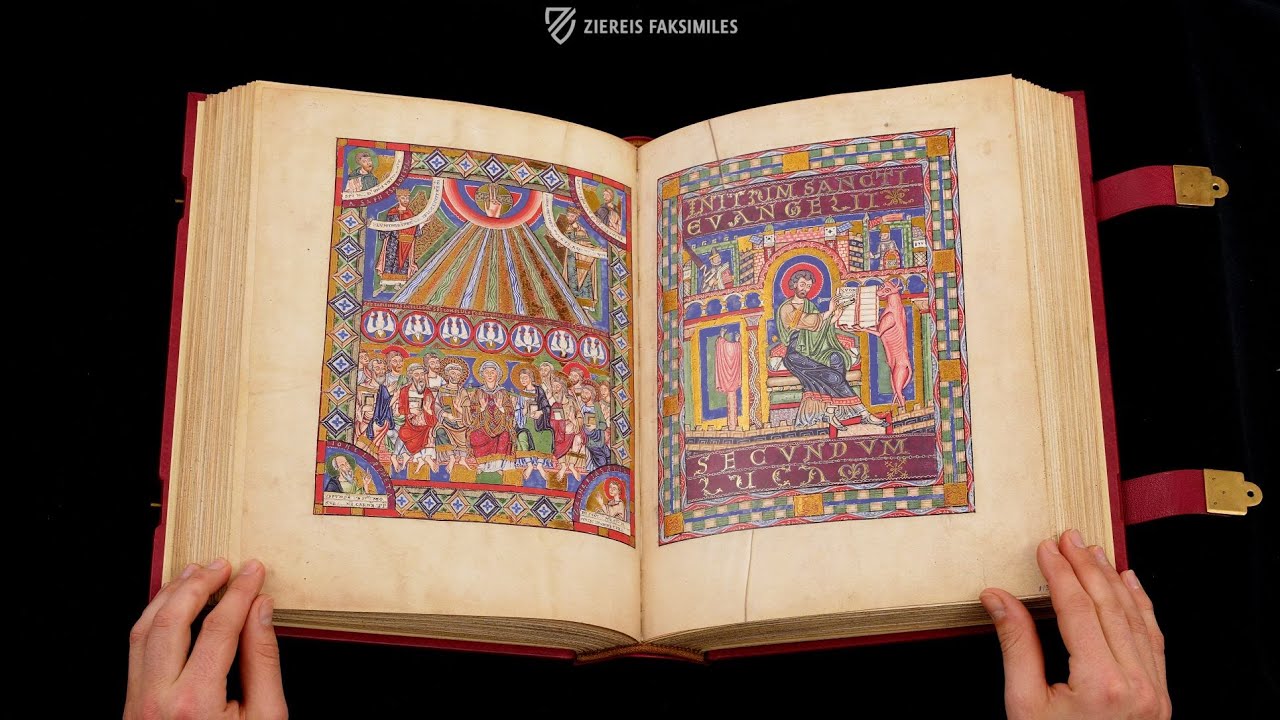

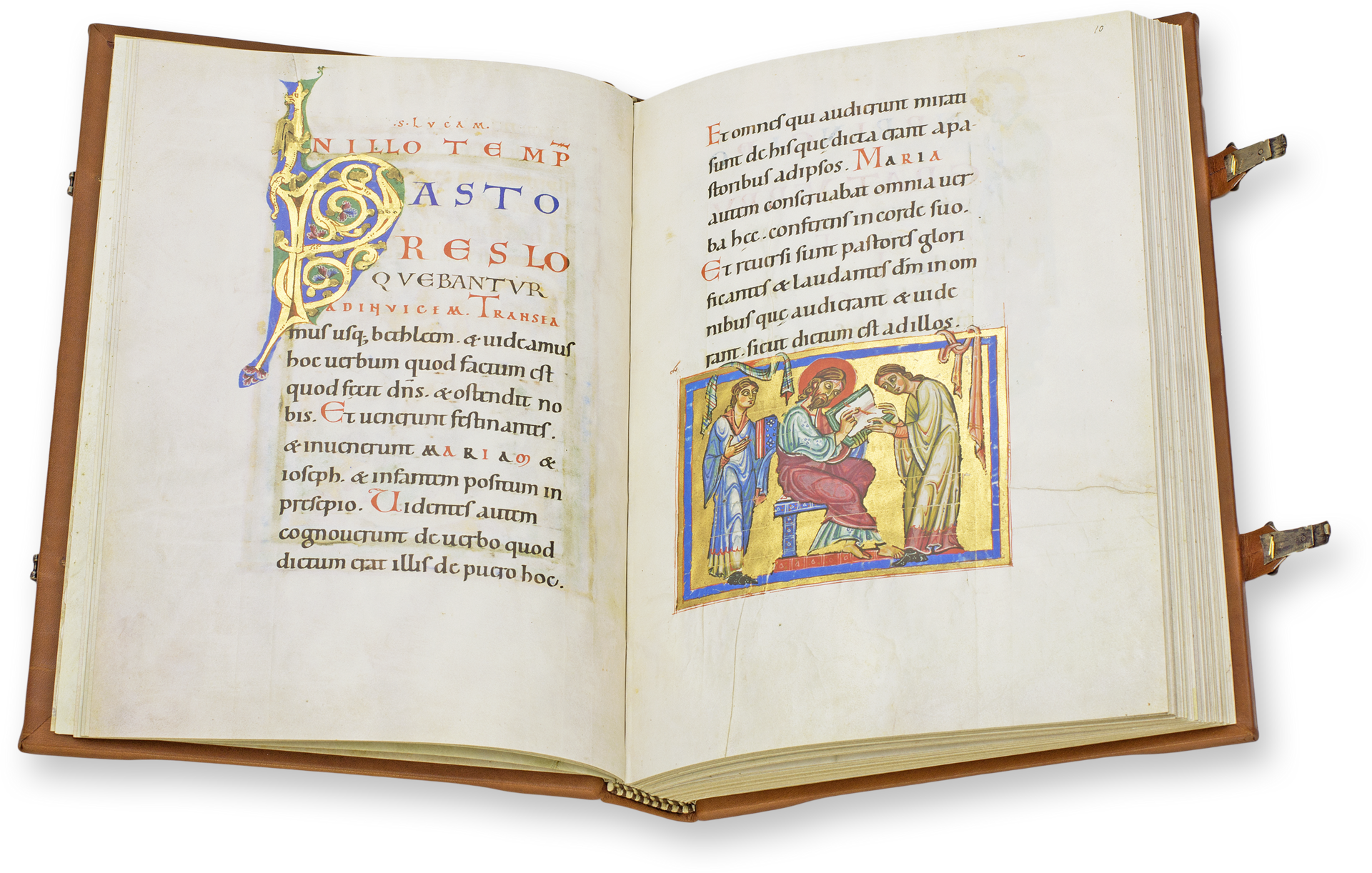

The Circumcision of Jesus

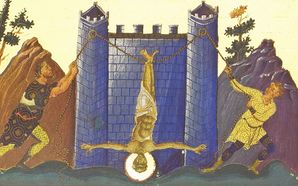

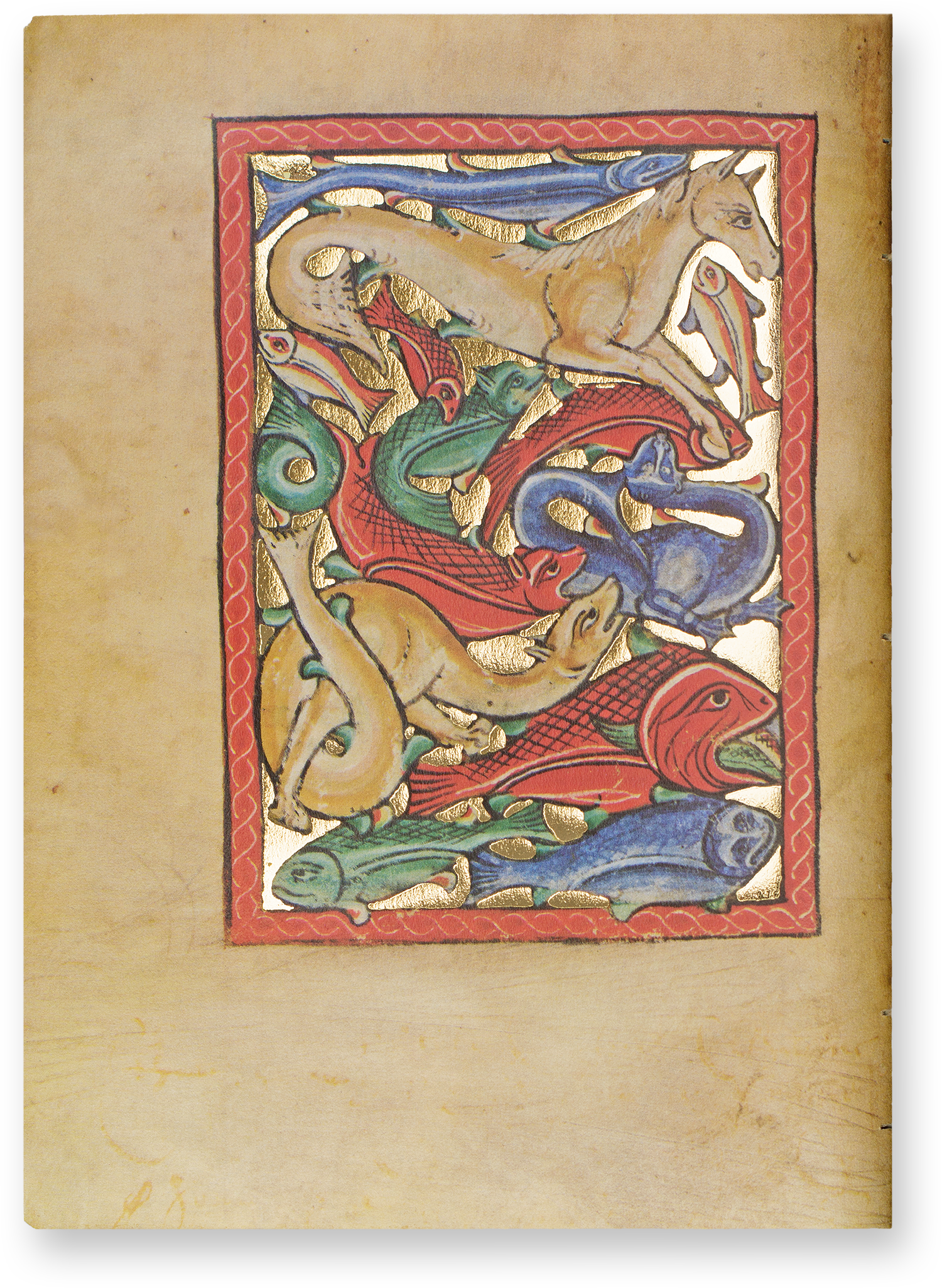

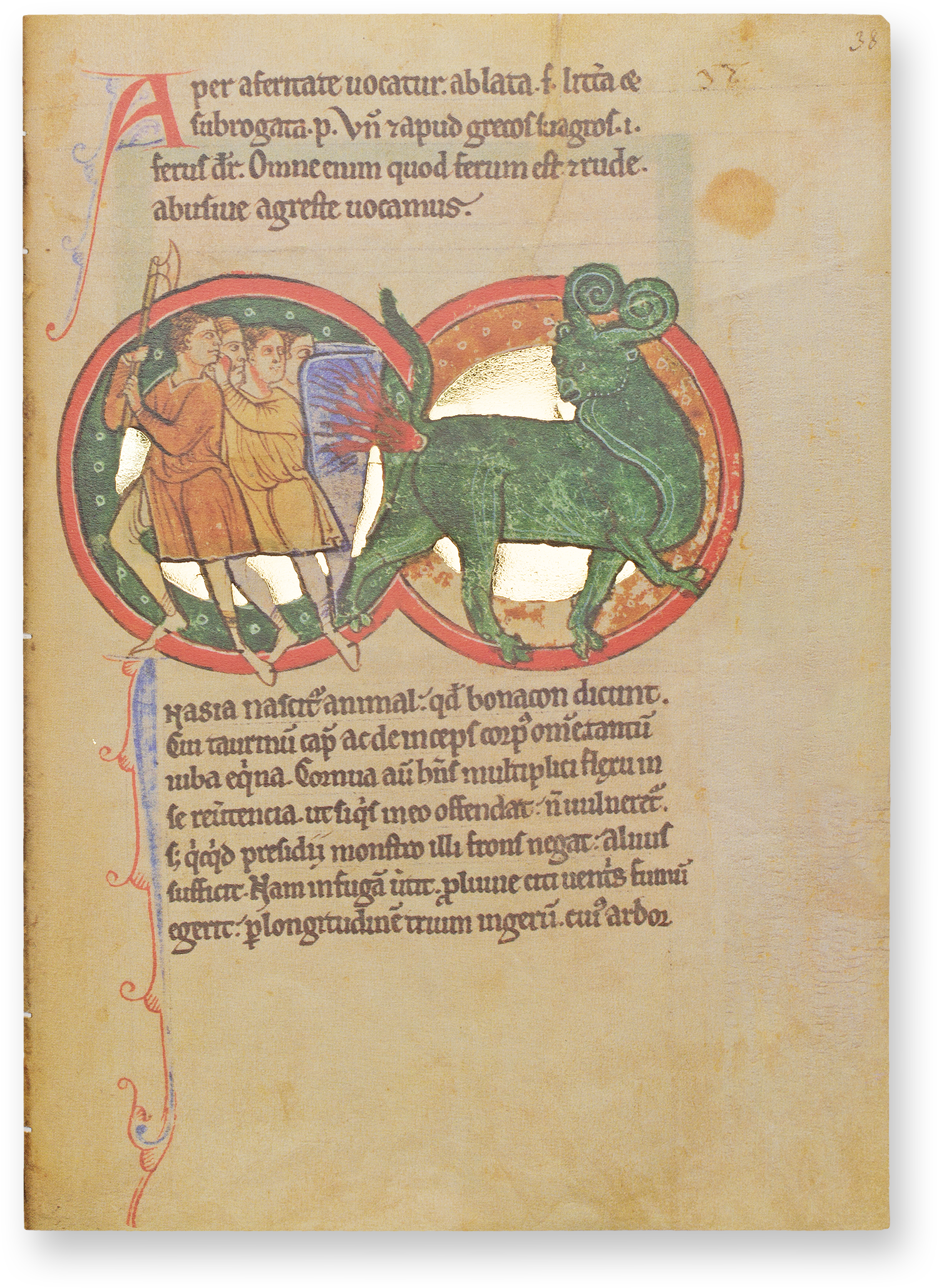

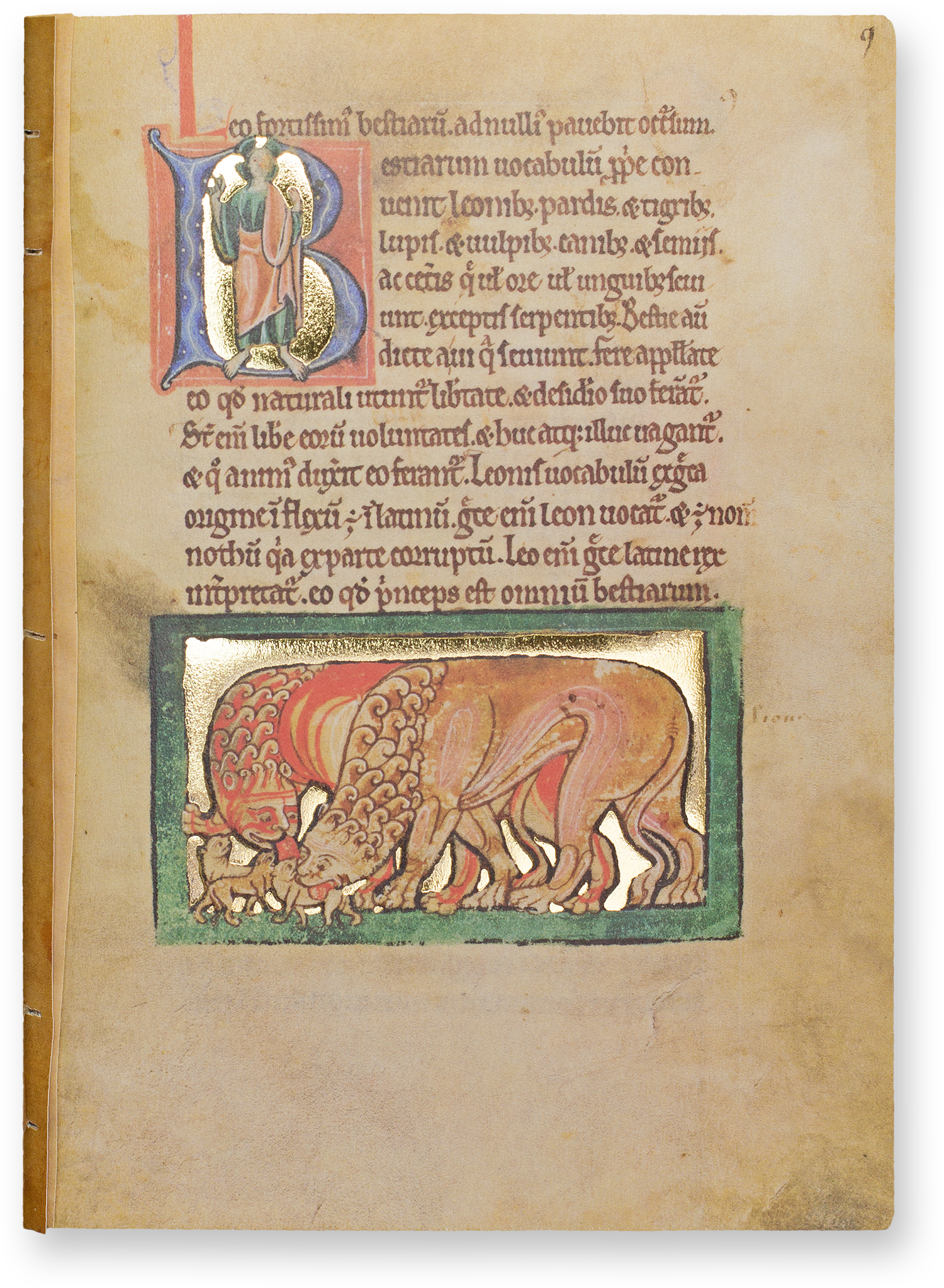

As told in the Gospel of Luke, Jesus was circumcised eight days after his birth in accordance with Jewish law. The figures in this scene display the rediscovered naturalism of Romanesque art, although the Rabbi’s scalpel is alarmingly large. This is thus one of the few standalone depictions of the Circumcision to predate the Renaissance.

Although a popular subject of Christian art beginning in the 10th century, the Circumcision was typically part of an image cycle. A large “P” initial introduces the page, a convention eagerly adopted by Romanesque artists from Insular illumination. The bas-de-page miniature on the other hand is obviously influenced by Byzantine art as evidenced by its burnished gold background and strongly-gesturing figures.

To the facsimile

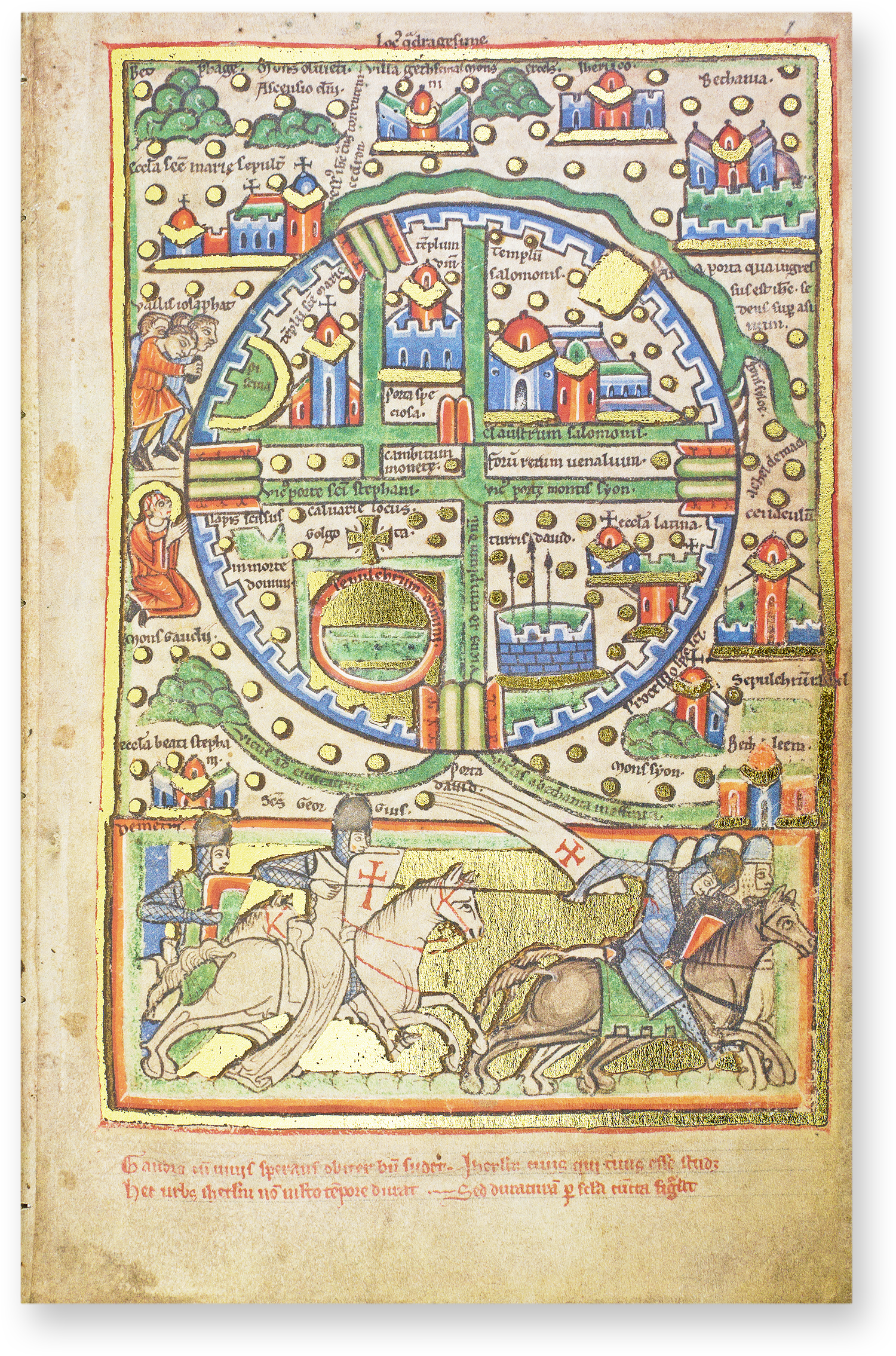

The Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem

On Christmas Day in the year 1100, Baldwin of Boulogne, the Count of Edessa, was crowned King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. He was the second lord of Latin Jerusalem and the first King of the new Crusader state that stretched north to Antioch and Edessa.

Although many of the participants of the First Crusade had returned to Europe, newcomers, largely consisting of those who had turned back from the First Crusade and now returned out of shame, arrived in 1101 as part of a minor Crusade. Baldwin expanded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, taking Arsuf, Caesarea, Acre, and Tripoli in Lebanon in addition to enjoying three victories over Muslim armies in the Battles at Ramla in 1101, 1102, and finally in 1105. He died in 1118 after having established defensible borders for his kingdom and established a chancellery that ensured stable governance for years to come.

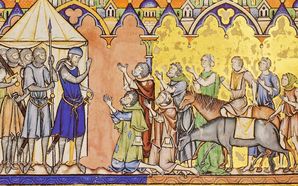

Baldwin of Boulogne became the first King of Latin Jerusalem

His successors continued to enjoy successes against their Saracen, Egyptian, and Turkish neighbors and expand the kingdom until it reached its largest territorial extent ca. 1140. Bringing the eastern Mediterranean under Christian European control was a tremendous catalyst to increased trade that funded the growing independence of Italian city-states from imperial rule, as well as filling the coffers of the Normans who controlled Sicily and southern Italy.

To the facsimile

The Fall of Edessa and the Second Crusade

The County of Edessa was the oldest of the Crusader states, founded by Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098, but the city fell to the Turks in the year 1144. It was an event that sent shockwaves through Europe and served as the catalyst for the Second Crusade, which was called by Pope Eugene III.

The Fall of Edessa served as the catalyst for the Second Crusade

It was the first in which crowned European monarchs participated, namely King Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. However, their hosts proceeded separately in 1147, did not coordinate well with each other or the Byzantines because all parties mistrusted one another, and as a result they were met with defeat and the effort was mostly abandoned by 1148. This was a pattern during the Crusades: just commanding and managing the logistics of their own forces so far from home was an almost insurmountable challenge, coordinating such forces among one another was beyond their organizational abilities. Much of this can be attributed to the personal rivalries that plagued these forces from top to bottom because they were not professional armies, they were feudal armies, the backbone of which were knights – warriors who devoted their lives to practicing the martial arts. It was through their prowess on the battlefield that they advanced themselves and as such competed for personal glory.

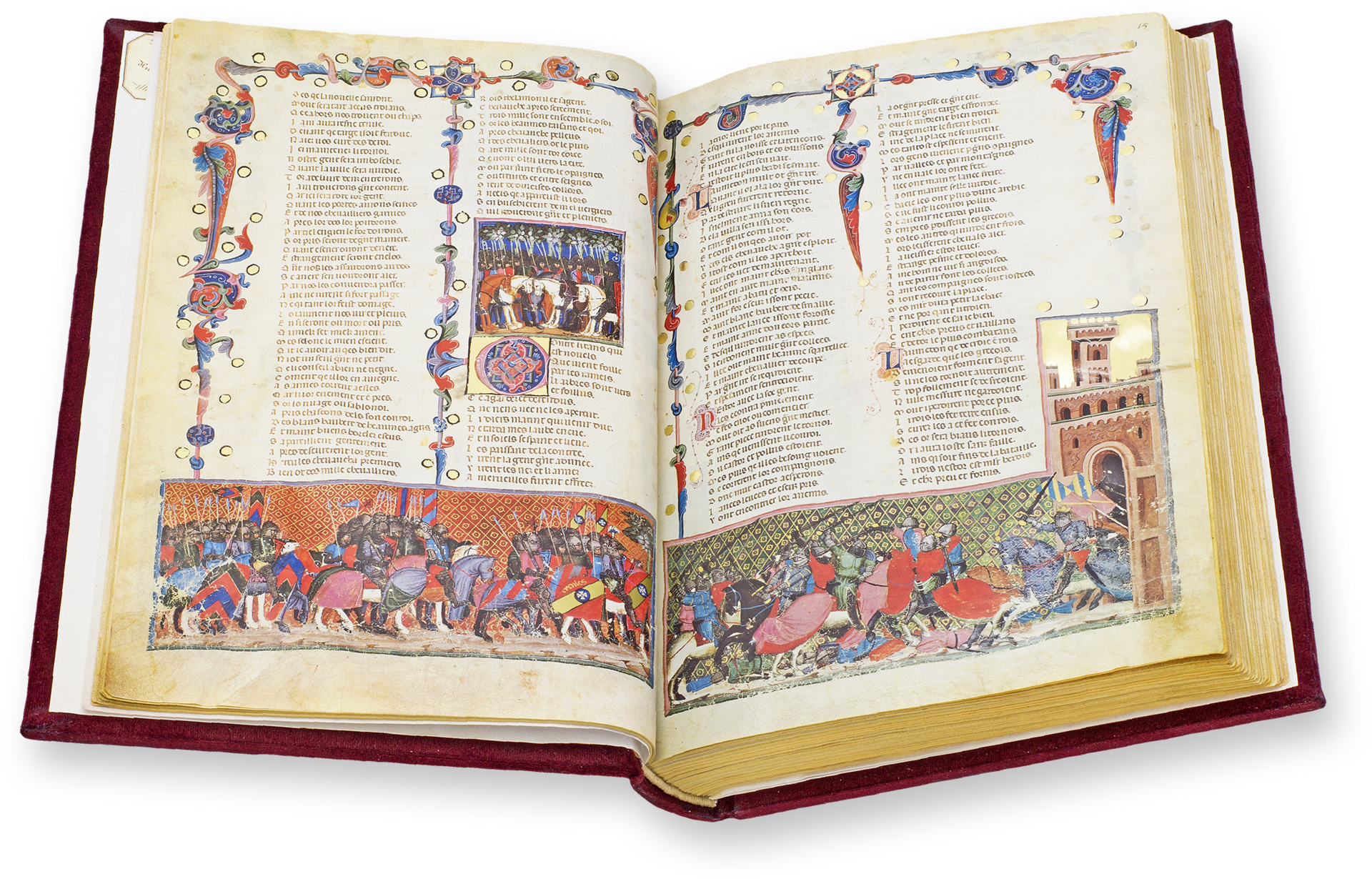

Although the Second Crusade was ultimately a failure, it did not recapture Edessa or take its other targets of Damascus and Ascalon. It did provide rich material for the troubadours of France and the minnesingers of Germany that would inspire future generations of knights to paint over their own coats of arms with a simple red cross on a field of white.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The Northern Crusades Begin

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The Holy Land was not the only target of the Second Crusade. Although many southern Germans were willing to participate in the campaign in the Levant, the Saxons to the north had more immediate concerns: various groups of pagan Slavs with whom they shared a contentious and violent border, the Wends foremost among them.

This so-called Wendish Crusade was given full papal support and the same status as other Crusaders with the same spiritual rewards due them, namely full remission of all their sins. Danes, Poles, and Bohemians joined the Saxons in their campaign of 1147. The Slavs attacked Saxon lands preemptively in the spring, and the Crusaders spent the summer first driving the pagans out of their territory before attacking various forts and important religious sites. The effort was met with mixed results, although the Crusaders were able to extract tribute from the Wends and other pagan Slavs, they were not successful in converting the majority of their population.

This would prove to be only the beginning of the series of conflicts that are known to us today as the Northern Crusades (also known as the Baltic Crusades), but the beginning of a state in the eastern Baltic controlled by the Teutonic Order that would eventually evolve into Prussia. The Baltic would become the battleground of German nobles like Henry the Lion, who because of personal rivalries with Barbarossa sought their own fortunes outside of imperial ambitions, namely, by northeastward expansion.

Experience more

The Reconquista Reaches Lisbon

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The third theater of the Second Crusade was on the Iberian Peninsula, where King Alfonso VII of León and Castile and King Alfonso I of Portugal were authorized to prosecute their campaigns against the Moors as part of the wider crusade. Portugal had only become a kingdom in 1143, but their forces were bolstered in June of 1147 when a multi-ethnic force of 6,000 Crusaders that had departed from England were forced to land on the Portuguese coast due to storms. They were convinced by Alfonso I of Portugal to join him in an attack on Lisbon, which was besieged and surrendered after four months in October. Many stayed and settled in the city, bolstering the future armies of the Reconquista, while others continued on to the Holy Land by sea.

This was an important turning point for the Reconquista in general, and delivered a valuable port city into the hands of the Portuguese that would eventually become their capital. The indulgences offered by the papacy to knights from across Europe would imbue the Reconquista with the Crusader spirit and continually attract new recruits. Christian forces in Iberia were now on the offensive and would never again relinquish that momentum.

Furthermore, the Treaty of Cazola (1179) designated zones of conquest between the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile to avoid any future Christian infighting. Not only was this the only undeniably successful effort of the Second Crusade, it began the historic relationship between the kingdoms of Portugal and England that would eventually be ratified into a formal treaty of alliance in the 14th century – the oldest alliance in the world that is still in force today.

To the facsimile

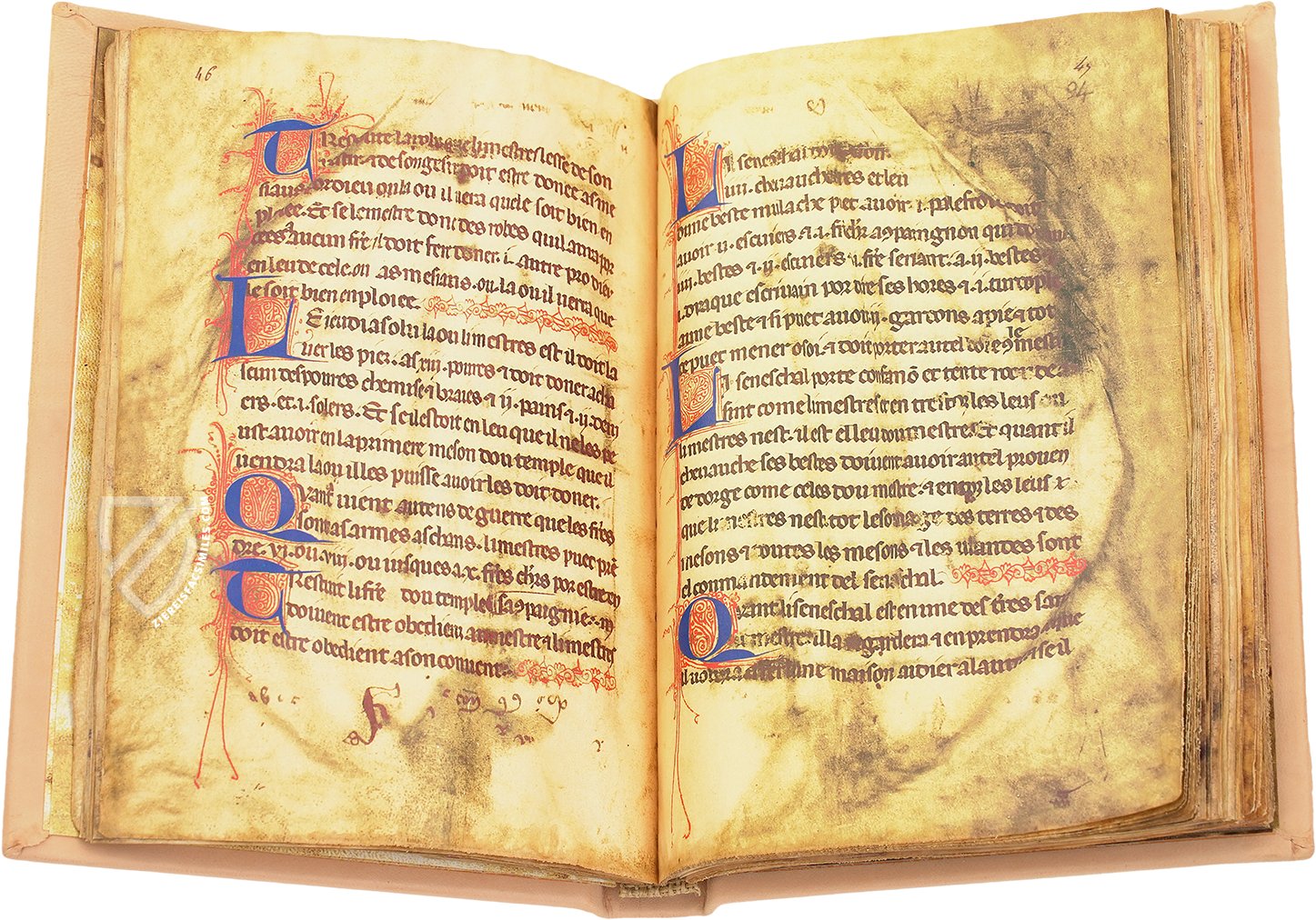

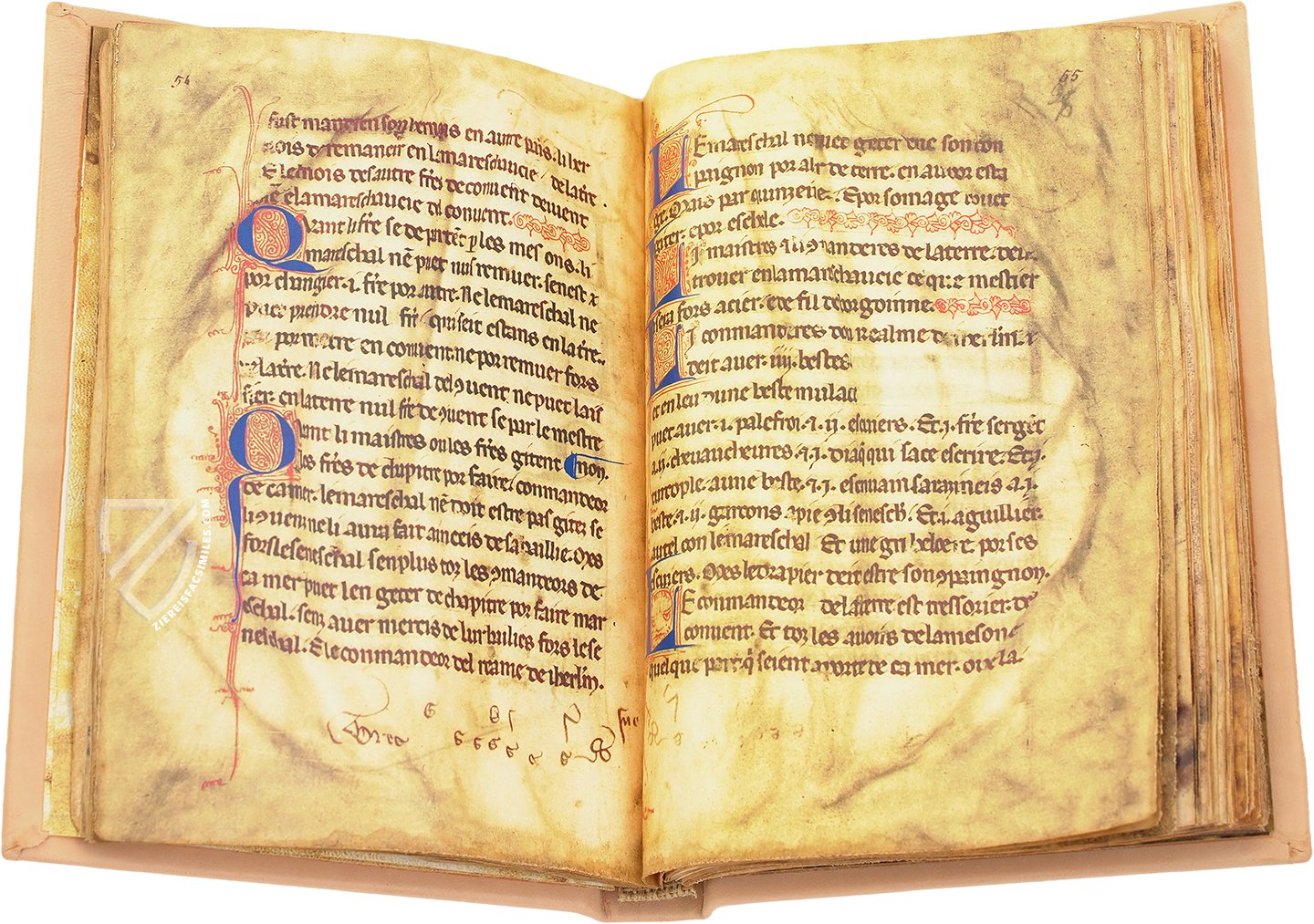

Emergence of the Monastic Military Orders

One of the most important and characteristic developments of the 12th century was the emergence of the monastic military orders, especially the Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, and the Teutonic Order.

The Templars were the richest and most famous. They were established in 1119 and made their headquarters in a palace on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, eventually possessing over 1,000 commanderies and castles from Jerusalem to the British Isles. Their primary role on paper was to protect pilgrims and serve as an elite shock force for crusading armies, but most of their membership was of a civilian nature, fulfilling support roles of a financial nature and making them one of the first multinational banking corporations. Crusaders would deposit their gold with the Templars in their own land and receive a check in cypher for that amount, and could then make withdrawals at various locations on their way to and while in the Holy Land.

The Templars were the richest and most famous monastic military order

The oldest order was the Hospitallers, founded in 1099 and headquartered on the site of the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist. As their name would suggest, they were initially responsible for the maintenance of hospitals and the care of pilgrims, but this soon expanded into providing them with armed escorts that eventually grew into a formidable force.

Finally, the Teutonic Order was founded in 1190 during the siege of Acre, it had a similar original mission to the Hospitallers and also developed into a formidable military force whose greatest impact would be in the East Baltic in the coming centuries.

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily

To the facsimile

Unlike during their Italian campaigns, Norman armies were almost always outnumbered by their Muslim foes in Sicily, but enjoyed a string of successes and thus built a myth of invincibility among their enemies and themselves. The Kingdom of Sicily included Sicily, Apulia, Calabria, and Malta and was established on Christmas Day of 1130 under the rule of Roger II, who was crowned by Antipope Anacletus II.

His rival, Innocent II, felt threatened by now having a powerful neighbor to the south, in addition to the emperor in the north, and so decided to turn one threat against the other. He instigated rebellion in the Normans’ southern Italian provinces along with a German invasion in 1137 and participated himself, but the campaign was met with difficulties. Eventually, the troops of Emperor Lothair II revolted and in 1139, papal troops were ambushed and Innocent II himself captured, forcing him to acknowledge Roger’s rights.

Roger II based his kingdom on the Byzantine model of the divine right to rule in order to uphold his ahistorical realm – Sicily had been an important player in the Mediterranean since antiquity due to its bountiful wheat and position in the central Mediterranean, but it had always been the pawn of greater powers and had never been a major independent player able to dominate its neighbors. Due to the infusion of bellicose Norman blood, this was about to change. The Normans valued knowledge and questioned the crews of all visiting ships about where they had been and what they had seen, recording the data and thus giving the Normans both an excellent knowledge of geography and of contemporary events.

Experience more

King Roger II Goes on the Offensive

After securing his own territory in southern Italy, most notably ending the self-rule of Naples, and implementing his Byzantine-inspired government, Roger set about expanding his dominions. His forces were able to take advantage of the Second Crusade by attacking the Byzantines in Greece: his forces attacked several islands in addition to sacking Athens, Corinth, and Thebes, wherefrom he carried off most of the Jews who were involved in the silk trade and who would subsequently form the basis of the Sicilian silk industry in Palermo. By 1153, he had captured Tunis and Tripoli, adding the richest parts of North Africa to his realm. Roger II made himself into one of the most powerful kings in Europe by the time of his death in 1054.

Roger II made himself into one of the most powerful kings in Europe

His successors would return Capua to Norman rule a year later, but would also lose the African territories he conquered to the Almohad Caliphate by 1160. Nonetheless, the Normans of Sicily dominated central Mediterranean trade, benefiting from the neutral position they had taken in the Crusades to continue friendly trade relations with Muslim and Jewish merchants. Just as they had done in Normandy, the Sicilian Normans created their own culture by combining the best parts of the constituent groups that made up their kingdom, thus benefitting from their varied talents both in peace and in war. They were in many way the dominant force in the Mediterranean at that time, both on land and sea, but in the process they surrounded themselves with enemies who would continue to conspire against them.

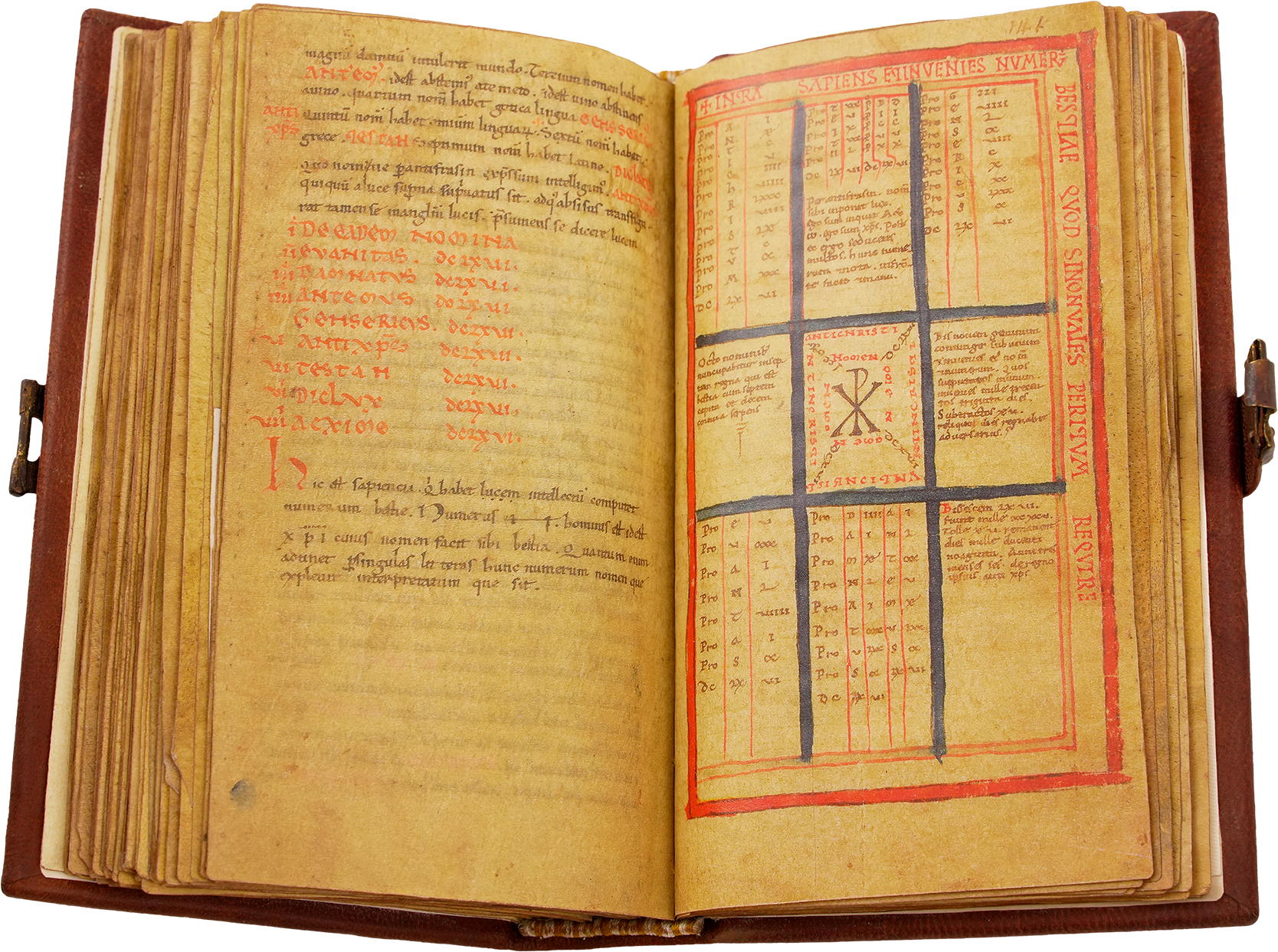

The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Emperor Frederick I, known today by his Italian epithet Barbarossa or “red beard”, is a towering figure in German history with a status similar to that of Arthur in Britain as a “sleeping hero” who will arise one day when his people’s need is greatest. Proponents of German unification in the late 19th century went so far as to declare Kaiser Wilhelm I, the first ruler of the new German Empire, to be the reincarnation of Frederick I.

He began his reign in 1152 at a time when imperial power was at a low-point and the German princes were strong and independent, his cousin Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony foremost among them. He was the first to technically be referred to as sacrum, “Holy” Roman Emperor in 1157, a title now applied generally to all the Roman-German emperors, even if the term Romanorum Imperator Augustus was the official title.

Frederick had distinguished himself as a soldier during the Second Crusade and would prove himself as a warrior time and again, both in bringing his German princes to heal and in pressing his rights in Italy. Frederick was remarkable for his endurance, ambition, and skill as an administrator in addition to his prowess on the battlefield. Although classically educated, he was not a philosopher king, and instead had the more practical sensibility of a bureaucrat so that he may be thought of as a warrior-administrator. Although he was able to subdue most of his rivals in Germany, receiving the submission of Henry the Lion in 1181, he was more prone to uphold the feudal tradition rather than reform it, and so the level of imperial authority he enjoyed would not be sustained for posterity.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Experience more

The Guelf and Ghibelline Struggle

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

During the first of six expeditions to Italy in 1154-5, Frederick I received the Iron Crown of Italy in Pavia and was crowned Emperor of the Romans at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. However, two parties emerged in Italy, those who supported Frederick’s vision of imperial rule in Italy, the Ghibellines who consisted mostly of rural noble families and smaller cities, and the Guelfs who opposed it, mostly consisting of larger mercantile cities. Loyalties were also strategic: those threatened by incorporation into the Papal States tended to be Ghibelline, while those facing imperial subjugation were Guelf.

Although Frederick I was successful in restoring imperial authority in Germany to what it had been during the lifetime of Otto I, the increasingly prosperous Guelf city-states of northern Italy comprising the Lombard League, along with a renewed alliance between the Normans of Sicily and the papacy, successfully resisted his attempts to assert imperial authority south of the Alps. Eventually, after being unable to overcome the combined might of the Italians on their own ground and being defeated at the Battle of Legnano, Frederick was forced to recognize the sovereignty of the Papal States and the independence of the Italian city-states, even if they still nominally owed him fealty, in exchange for papal recognition of the emperor as overlord of the imperial church at the Peace of Venice (1177) and the Peace of Constance (1183).

To the facsimile

Sicily Becomes Part of the Holy Roman Empire

In spite of these setbacks, Frederick Barbarossa was able to engineer a political coup in southern Italy when, in spite of the objection of Pope Urban III, he married his son and heir Henry VI to Constance, heiress to the Kingdom of Sicily. As the daughter of King Roger II, she came into this position because her nephew, King William II, died childless. So it was the great Kingdom of Sicily that the Normans had established and enriched came into the sphere of imperial politics. The papacy’s worst fears had now come true as it was seemingly surrounded by the territory of the Holy Roman Empire.

Frederick I made the Pope's worst fears come true

After resisting attempts by both her Norman relatives and her German husband to undermine her personal authority, she managed to hold on and had her three-year-old son Frederick was crowned King of Sicily upon the death of his father in 1197. She envisioned a purely Sicilian destiny for her son, and as part of a policy of renewing the erstwhile papal alliance, attempted to dissolve her imperial ties, making no claim for her son to the titles of King of the Germans or Emperor of the Romans. As her health failed in 1198, she put her son under the guardianship of the newly minted Pope Innocent III, one of the most powerful figures to ascend to the throne of St. Peter. He would cultivate young Frederick into the model of a Renaissance prince before the concept existed or the Italian Renaissance had even begun, he would be known to history as Frederick II, the stupor mundi or “wonder of the world” and the greatest ruler of the 13th century.

Experience more

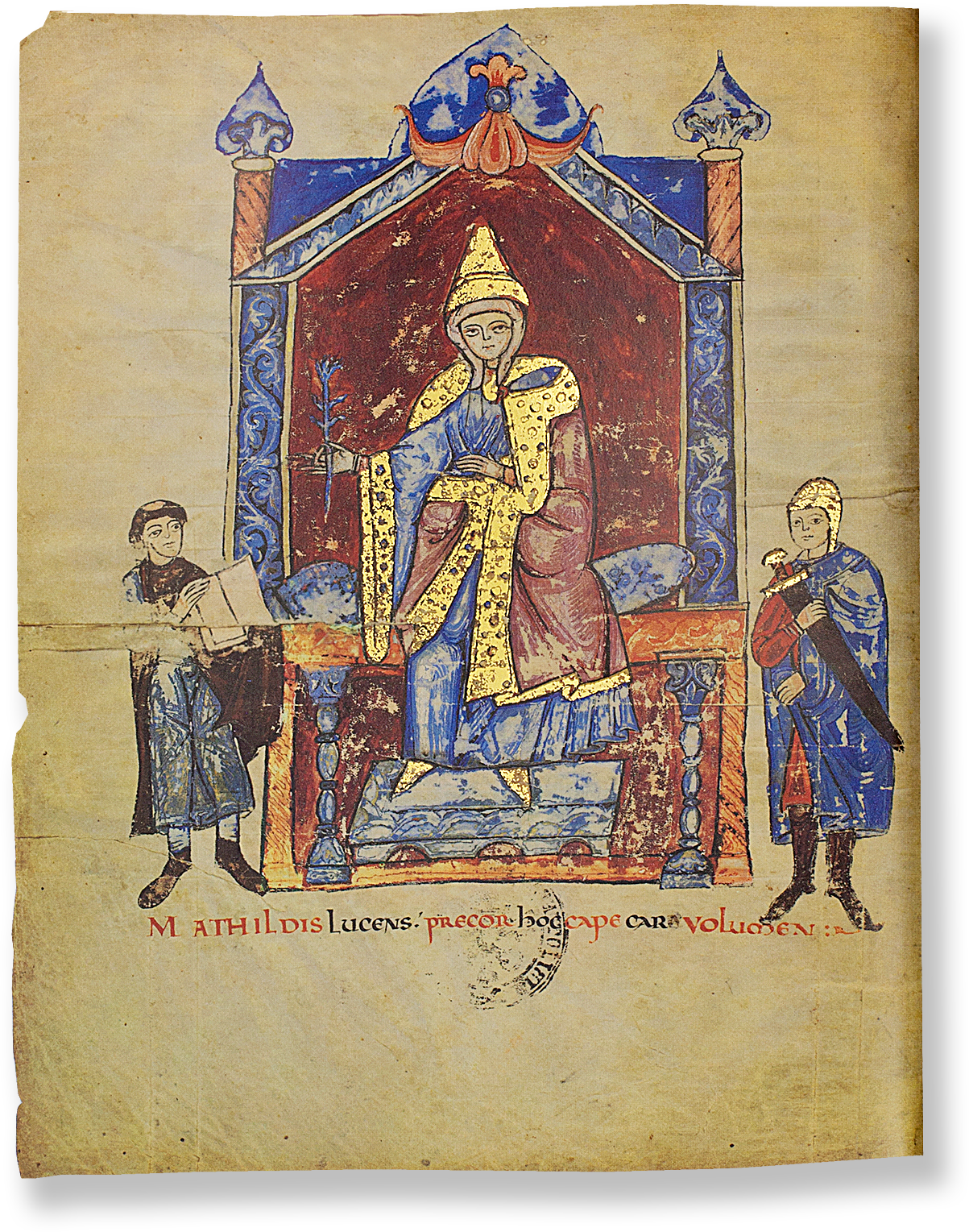

Matilda, Empress of the Romans and Queen of the English

King Henry I of England, fourth son of William the Conqueror, made a fortuitous match for his daughter Matilda in the form of the powerful Emperor Henry V. They were married in 1114, and despite it being an arranged marriage to an older man, as was common in those days, the match appears to have been amiable and Henry could be described as a mentoring figure. She took an active part in the imperial government, even ruling in Italy for two years on her husband’s behalf while he was in Germany. However, they failed to produce a child before Henry died of cancer in 1125.

Matilda was the first woman to claim the English throne

The 23-year-old Matilda returned to Normandy and a year later, her father made a new match for her: Geoffrey d’Anjou. The match would end the rivalry between Normandy and Anjou, and her husband would prove to be a great warrior, but it was a step-down for Matilda who had hoped for at least a royal match, and her new husband was 11 years her junior.

The birth of her son, who would come to be known as Henry II, would reignite her royal ambitions. She would become the first Queen of England to attempt to rule in her own right as regent for her son. Matilda, although capable and experienced as a ruler, had a tendency to act haughtily and flaunt her imperial title, which, in addition to the fact that she was a woman, earned her the resentment of many nobles. Therefore, a long and devastating civil war would have to be contested before her son could come of age and fight for his own right to be crowned King of England.

The White Ship Disaster and the Anarchy

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Henry I ruled from 1100 to 1135, during which time he reigned in the power of the nobles, built on Anglo-Saxon legal traditions, increased the role of law, and founded new institutions like the Royal Exchequer.

However, on November 25th, 1120, his only son and heir was killed in the White Ship Disaster when he and his companions were drowned in the English Channel. After attempting to establish his daughter Matilda’s infant son Henry d’Anjou as his heir with her as regent, Stephen of Blois usurped the throne after the death of Henry I in 1135. A civil war between the supporters of Matilda and Stephen, known as the Anarchy, would last until 1153.

King Stephen is often referred to as Bad King Stephen and this was not because he was a cruel tyrant, but rather because he was simply a “bad king”: the same chivalrousness and generosity that had won him favor in becoming king now made him weak because he had so little left to give. Therefore, the headstrong barons of England did not fear him and increasingly engaged in private wars. Men who had been sworn to uphold the peace and security of one of the richest kingdoms in England were now ravaging it, and mercenaries from the Low Countries and Germany began flooding the country. When paid, these mercenaries were deadly effective warriors, when not, they became large bands of brigands pillaging the countryside. England, the South in particular, was devastated as a result.

Experience more

Eleanor of Aquitaine, the Most Powerful Woman of Medieval Europe

Born to one of the most ancient Frankish houses, a scion of the Carolingians, Eleanor of Aquitaine was from the most noble of stock. She was charming, witty, and described as perpulchra– more than beautiful. Inheriting the duchy in 1137 at the age of 15 made her the most eligible bride of her day and one of the richest and most powerful women in all Europe, thanks to Aquitanian law rooted in Roman custom that allowed women to inherit property.

She was married to the young King Louis VII of France three months later and even joined him on the ill-fated Second Crusade, but they were not well matched. Louis was dour and pious in the manner of a northern Frank, while Eleanor was from the famous court of her grandfather William IX, called the First Troubadour, and was of a more secular persuasion that moralistic contemporary chroniclers found hedonistic, and she was plagued by rumors concerning her virtue as a result. Their marriage was annulled in 1152 as Louis blamed her for not producing a son.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the richest and most powerful women in all Europe

She immediately became engaged to Henry d’Anjou, King Louis VII’s greatest rival, and married him eight weeks later. Already the Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy inter alia, the addition of Aquitaine meant that the claimant to the English throne now ruled more lands in France than King Louis VII. The humiliation of Louis was completed when Eleanor proceeded to give her new husband not one but five sons, four of whom would live to adulthood and two of whom would be kings of England.

She was Eleanor of Aquitaine: wife to two kings, mother of two kings, and one of the biggest players of 12th century Europe.

To the facsimile

Henry II and the Plantagenet Dynasty

King Henry II of England was arguably the richest, most powerful, and most ruthless sovereign of the 12th century, his lands, called the Angevin Empire (a nod to his roots in Anjou) stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenes Mountains. His coronation marked the end of the strictly Norman dynasty established by his maternal great grandfather, William the Conqueror, and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty that would rule England until 1485.

Henry II's coronation marked the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty

His legal reforms formed the basis of common law, and his efforts to create a more efficient model of rule helped lay the foundations for the English state and army. He was first to require scutage from his nobles – a military tax collected in lieu of knight’s fees, the annual service owed by knights to their lords and in turn by their lords to the king. This had the duel effect of reducing the private armies of his lords, due to the cost of paying scutage, while also creating a “war chest” for the king’s use.

This was crucial for Henry, who had to put down two uprisings, known as the Great Revolts, by his ambitious sons who were encouraged by their mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who had become estranged from her husband, and the kings of France who sought to gain from infighting within the Angevin Empire. In 1189, his son Richard, who had fought on his father’s side in the Second Great Revolt, suddenly attacked and overthrew his aging father because of a rumor that he would be passed over in favor of his younger son John, and Henry died on July 6th of that year. When Richard visited his father’s body, blood ran from the old king’s nose, interpreted in those days as a sign of displeasure with his rebellious son.

Experience more

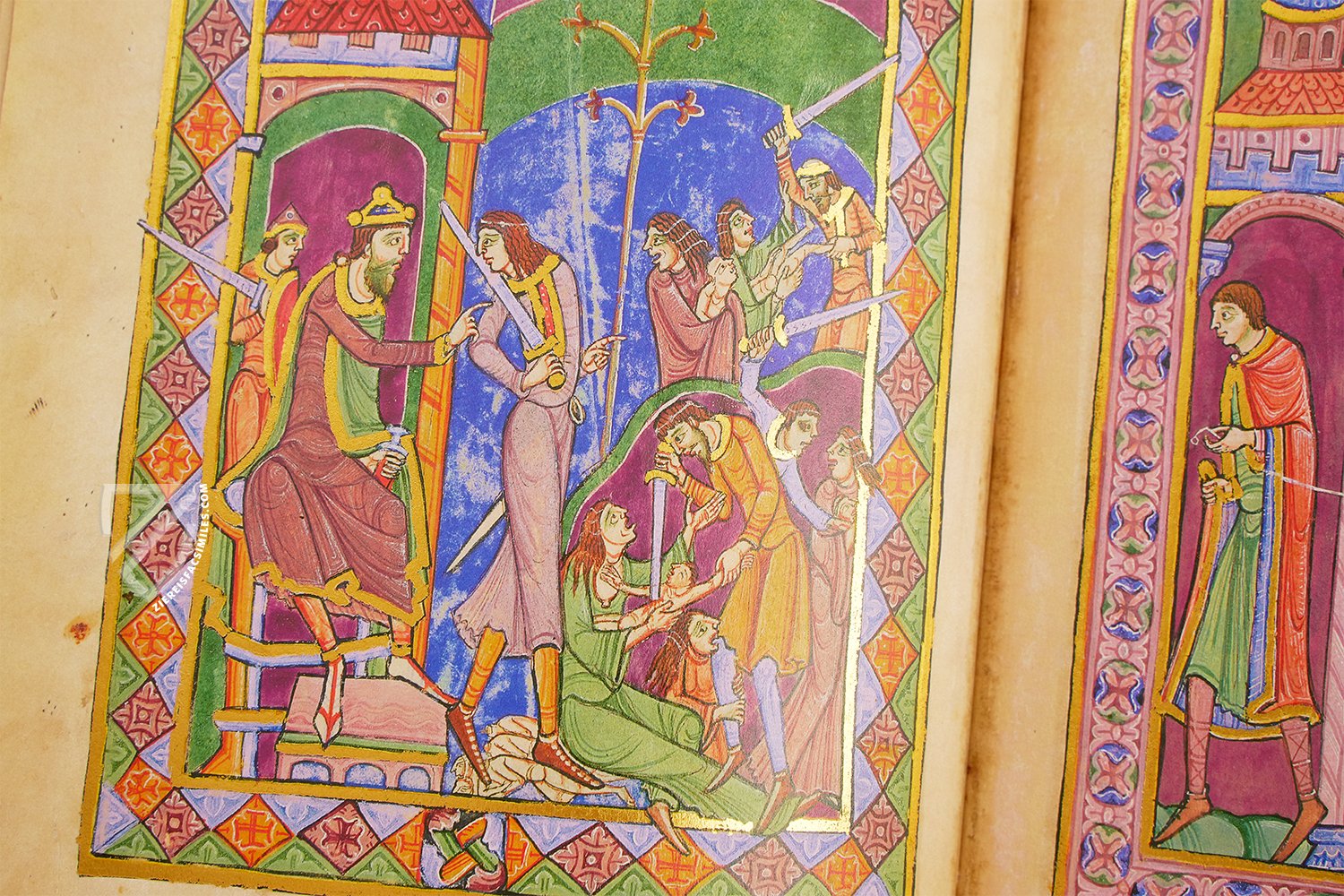

The Story of Thomas Becket

The relationship between Henry II and Thomas Becket is one of the most famous tales of the entire Middle Ages and a useful example of medieval society. After the Archbishop of Canterbury died, the King appointed his Chancellor to the position in 1162, believing that his close friend and confidant would prove a powerful ally in bring the church to heal, but in this he could not have been more wrong. Becket apparently underwent a transformation and undertook the persona of a pious defender of the church and in doing so became a thorn in the King’s side. Whether this was genuine or merely a symptom of his vanity and ambition remains debatable.

The conflict boiled over during the Christmas season of 1170 after Thomas Becket excommunicated some of Henry’s supporters. While feasting in Normandy with his entourage, the King supposedly raged at his circumstances, saying

What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!

Four low-ranking knights proceeded immediately to cross the English Channel to Canterbury Cathedral, where they attempted to seize Becket, who refused, and was consequently murdered before an altar. The event made a martyr of Becket and scandalized Henry across Europe.

Henry eventually was able to manipulate the situation by doing penance in 1174, atoning for his sins and accepting blows from rods wielded by the clergy of Canterbury and in the end was able to turn the cult of Thomas Becket in his own favor after keeping vigil at Becket’s tomb, which he later patronized as a pilgrimage site.

Barbarossa Departs for the Third Crusade

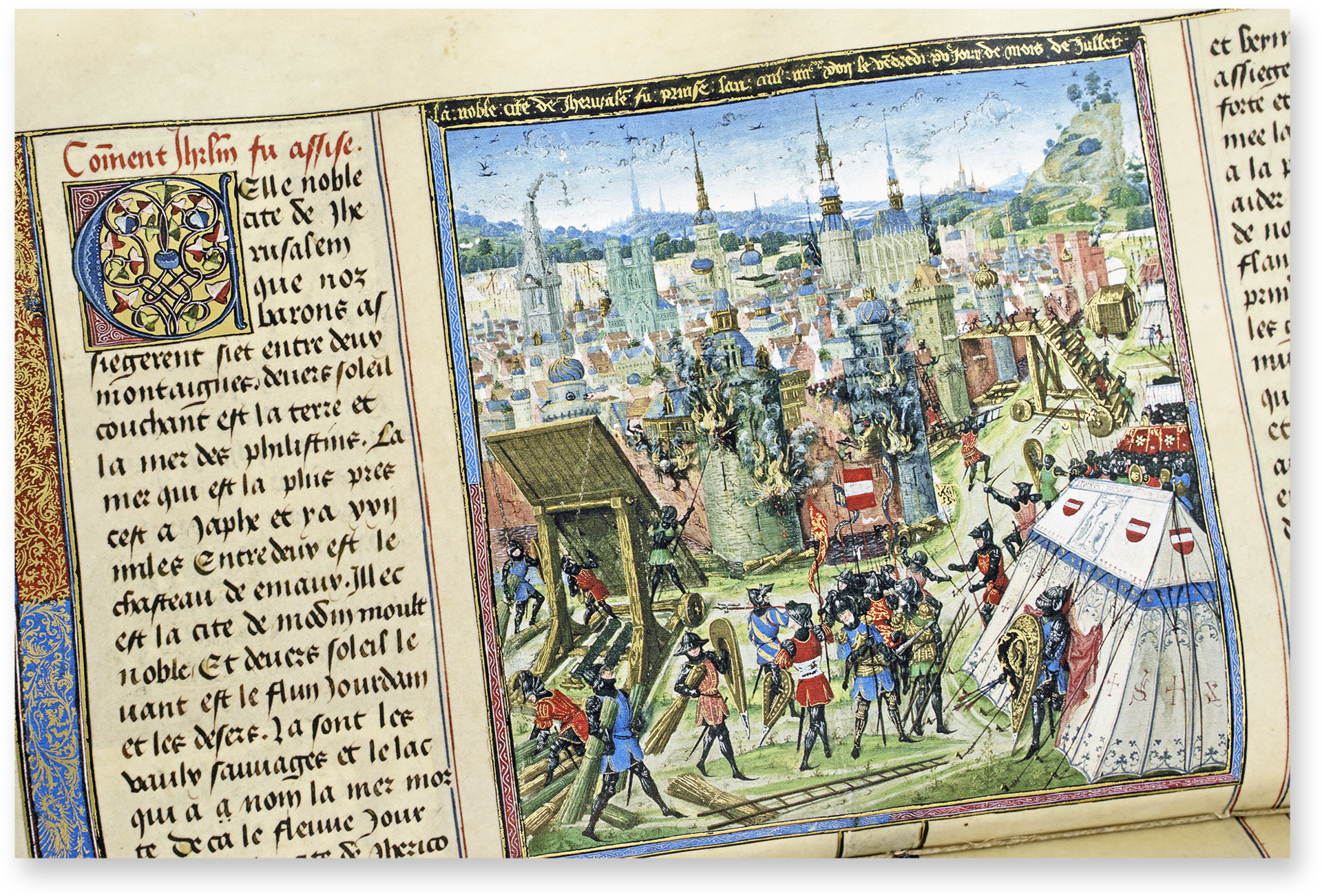

In 1187, the army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was utterly defeated by an Ayyubid army led by the great Saladin. Only 3,000 of the original 20,000 soldiers of the Crusader army escaped, leaving garrisons in their kingdom woefully undermanned for their own defense. The result was the systematic loss of most of their territory: Saladin quickly captured 52 forts and walled towns, culminating in the surrender of Jerusalem in October.

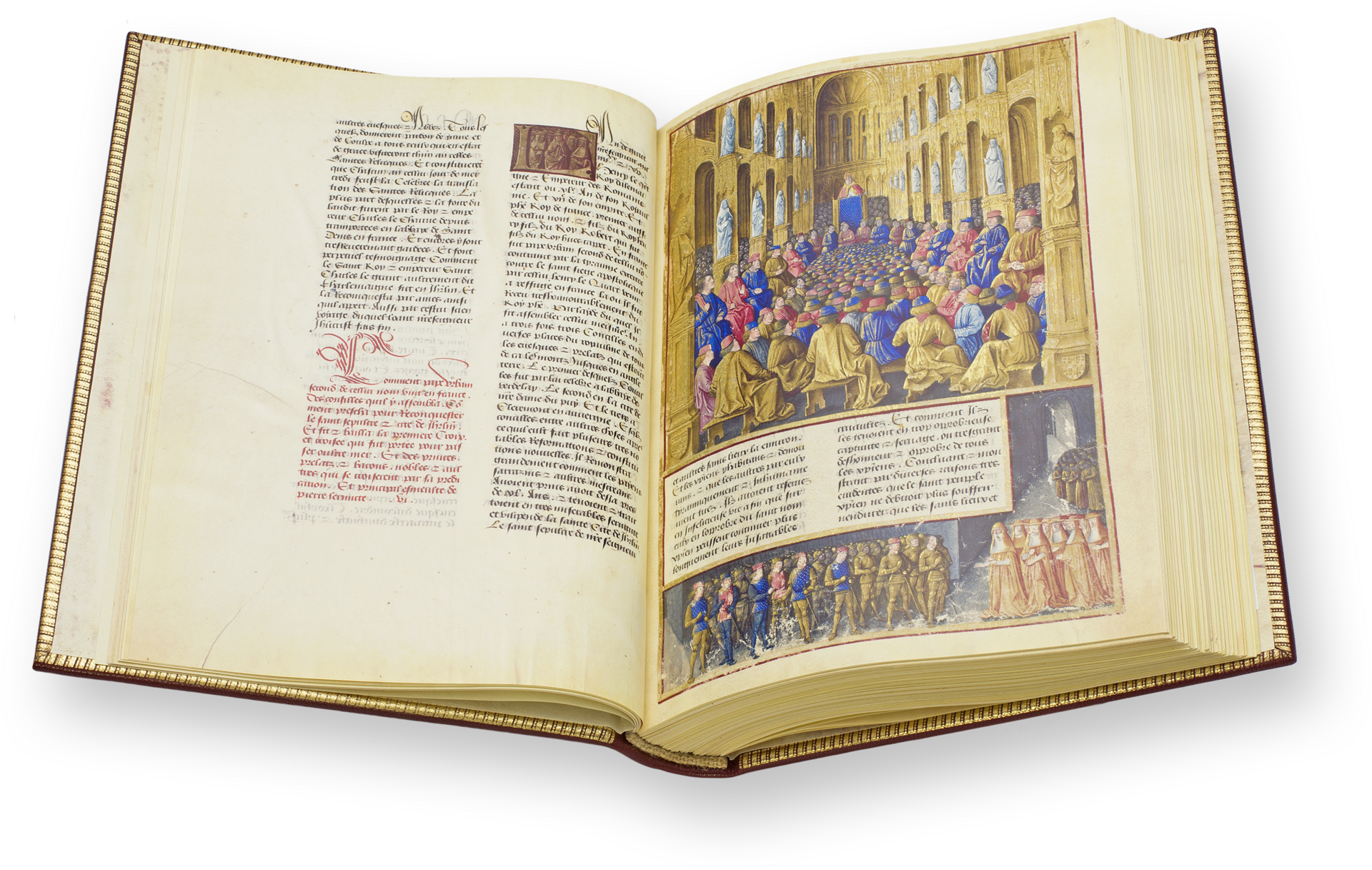

After Saldin seized large parts of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Latin rulers initiated the Third Crusade

The “Saladin tithe” was immediately established in the West to fund the Third Crusade, which was answered by the crowned heads of England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire in 1189. The largest host by far was commanded by Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, rumored to number 100,000 including 20,000 knights, an army so big no fleet could transport it. Even if it was only a fifth of that size in reality, it would have still been a most formidable army, and it is recorded that Saladin and other Muslim leaders feared it greatly and were gathering forces to oppose the veteran warrior who was now nearly 70.

However, Barbarossa died after falling from his horse while crossing the Saleph River, either drowning because of the weight of his armor or suffering from a heart attack due to the shock of the cold water. Most of the army disbanded and headed back to Germany, but his son Frederick VI of Swabia continued on with a force of about 5,000 men. Unable to reach Jerusalem, where they planned to bury Frederick, his body was preserved in a barrel of vinegar but was rapidly deteriorating, forcing them to bury him, dividing his remains between churches in Antioch, Tyre, and Tarsus in the manner of a saint.

To the facsimile

The English and French Fleets Finally Arrive

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The personal rivalry between the crowned heads of England and France delayed their cooperation on the Crusade and as such, their forces did not arrive until 1191. King Philip II of France, known as Philip Augustus, was a skilled politician and administrator who was also the first person to style himself “King of France” instead of “King of the Franks”, a distinction which first appeared ca. 1190. King Richard I of England, known as Richard the Lionheart, was a military genius but an otherwise inept ruler who did not speak English and did not even particularly like England – he spent only about 6 months of his reign there and preferred sunny Aquitaine.

Their conflict was not only a matter of interest: the men had personal conflicts resulting from their divergent personalities, and from Richard’s broken engagement to Philip’s sister. After seizing the crown from his aging father, Richard took up the Crusade that Henry II had agreed to with Philip Augustus.

A storm shipwrecked his sister and fiancé on the island of Cyprus, along with much of the funds for the campaign, and all were seized by a rebel Byzantine prince who controlled the island. Richard thus conquered the island, which became an important Crusader outpost for the next four centuries.

He arrived to assist Philip at the siege of Acre in June, and the subsequent surrender of the city returned 1,000 prisoners as well as the True Cross and a large ransom for the captured garrison. Feeling slighted and in ill-health, Philip returned to France after the successful siege, along with Leopold V of Austria whom Richard had also offended, leaving the remaining Crusader army firmly in the hands of the Lionheart.

To the facsimile

Saladin, Richard the Lionheart, and the Battle of Arsuf

Saladin was a man known both for his skill as a general as well as being one of the most chivalrous figures of the Middle Ages, which gained him great respect and renown among Europeans. Although Saladin would not have to face the old warhorse Frederick I as he feared, another opponent would prove to be as great of a chivalric warrior as he: Richard I the Lionheart.

Richard was one of the greatest warriors of his day, just like his father and grandfather before him, and he relished in playing the role of the chivalric warrior. That being said, while he could be most gracious and chivalrous to captured Muslim princes, he was also known for his ruthlessness and cruelty toward common captives. This is evidenced by an 1191 incident following the fall of Acre when he ordered the decapitation of all 2,700 members of the Muslim garrison in view of Saladin and his army after Saladin had failed to make the first payment of their ransom.

Subsequently, Richard was marching his army to Jaffa, vital for launching an attack on Jerusalem, when he was attacked by Saladin at Arsuf. Although outnumbered, the Crusader army held together in the face of the onslaught and delivered a shattering charge against the Muslim army, who were routed with terrible losses. Richard the Lionheart successfully upended Saladin’s reputation of invincibility and earned his respect, but was never able to retake Jerusalem itself, largely hindered by infighting between Guy and Conrad, rival claimants to the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, or what remained of it.

To the facsimile

A Compromise to End the Third Crusade

Saladin and Richard both realized that a negotiated three-year peace was the best for both sides. Richard could not get his army to focus on either a siege Jerusalem or an attack on Saladin’s power base in Egypt. Saladin’s position was growing weaker after another defeat at Jaffa, which he had seized and then been driven out of with heavy losses, once again by numerically inferior but more heavily armed and armored Crusaders, and could not hope to drive them out of the Holy Land completely.

Richard and Saladin made a compromise to end the Third Crusade

Therefore, a compromise was made on September 2nd, 1192: Jerusalem would remain in Muslim hands but would be opened up to Christian pilgrims and merchants once more, while Richard’s conquests restoring most the coastal territory of the Kingdom of Jerusalem between Jaffa and Antioch would be respected by Saladin. Therefore, Richard departed for home the following month. A subsequent German Crusade in 1197 restored overland connections between many of these strategically and economically important cities. Although neither side was happy with the result of the peace, both benefited greatly from increased trade.

Saladin would die the following year of yellow fever, while Richard would be shipwrecked and subsequently captured and ransomed by Leopold V of Austria, whose standard he had cast down from the walls of Acre. Richard’s ransom would bankrupt England, and he would spend the remaining years of his life retaking lands in France that Philip Augustus had seized in his absence until he was fatally wounded by a crossbow bolt on March 25th, 1199 and laid to rest at the feet of his father at Fontevraud Abbey.

Experience more

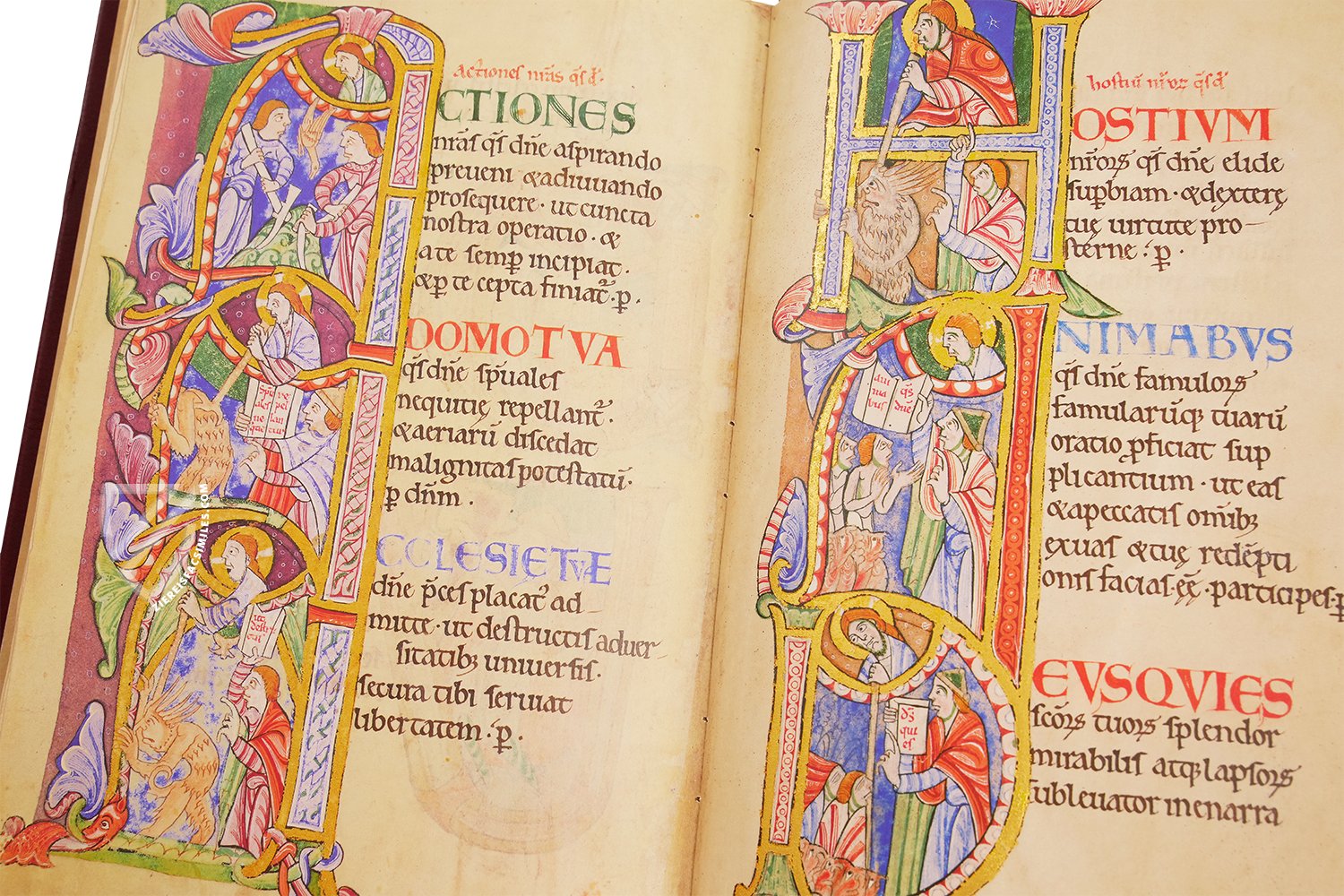

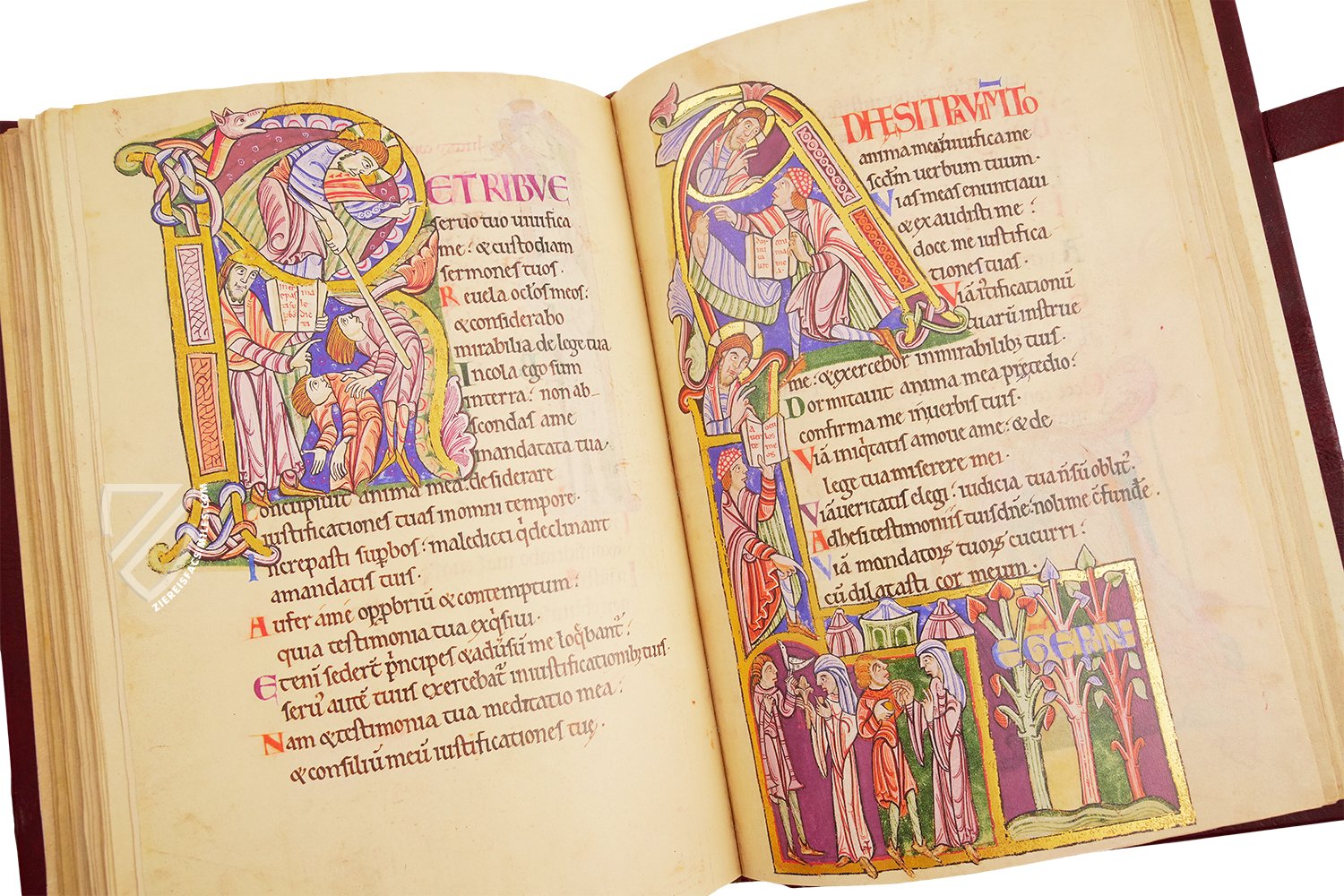

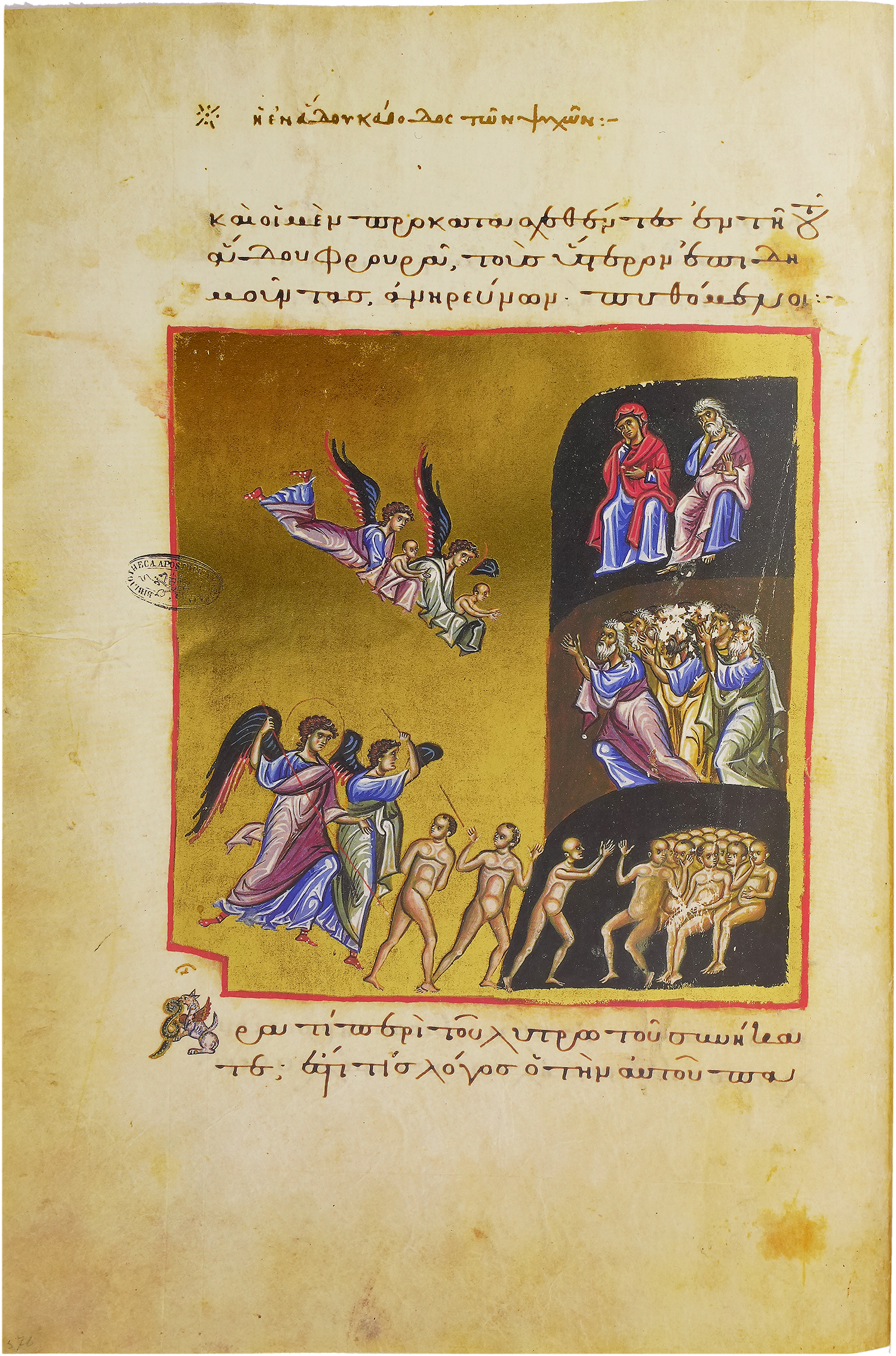

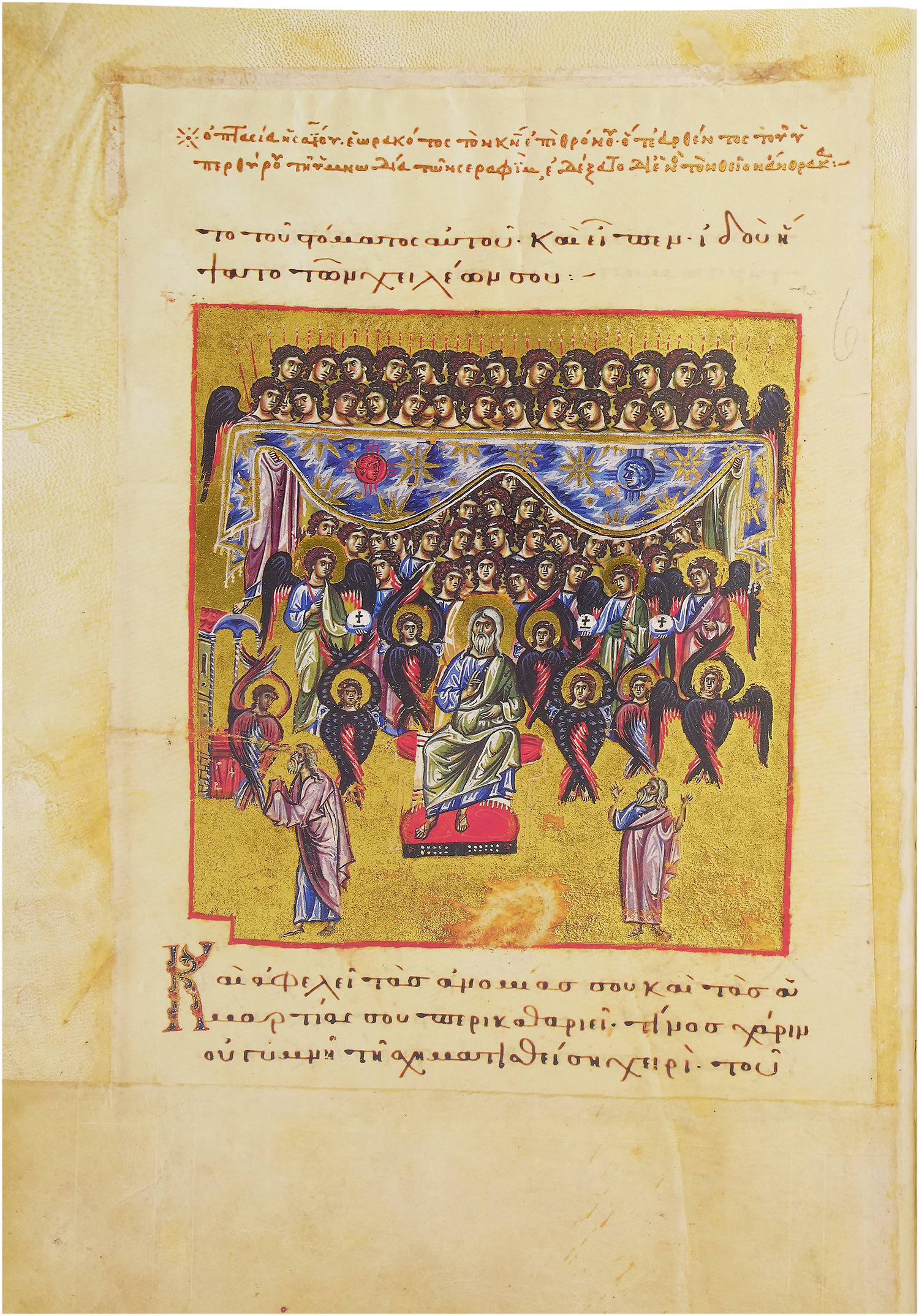

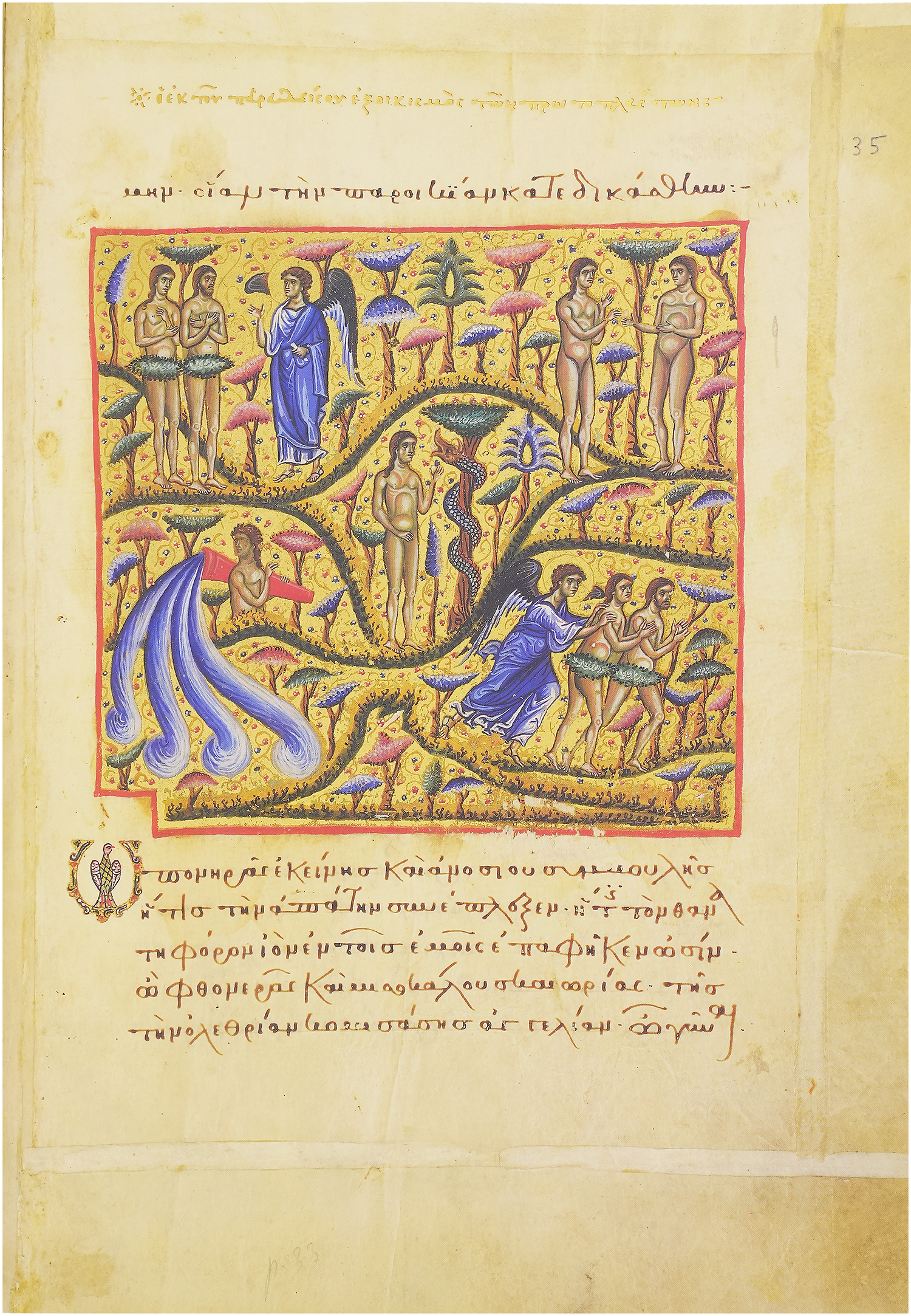

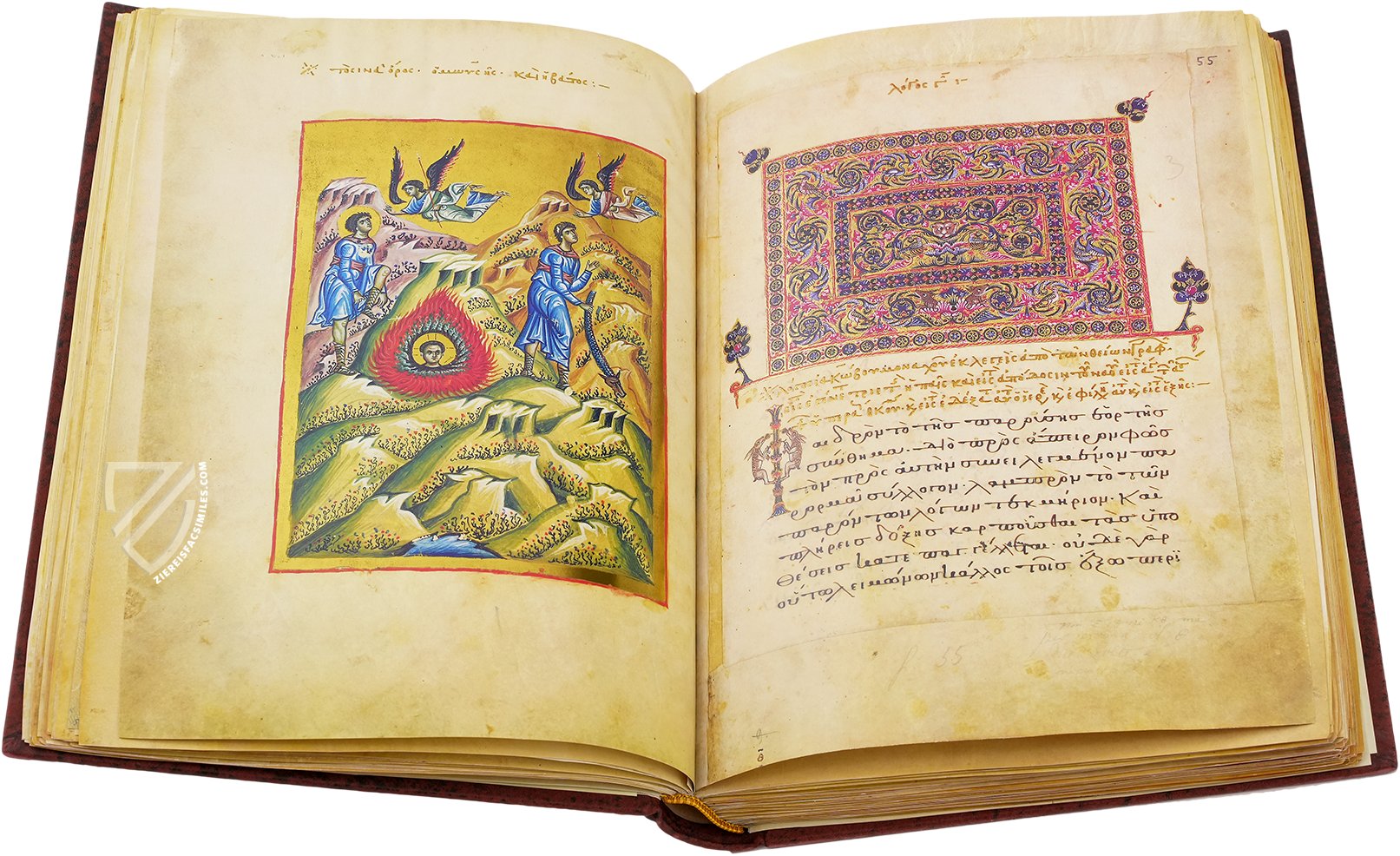

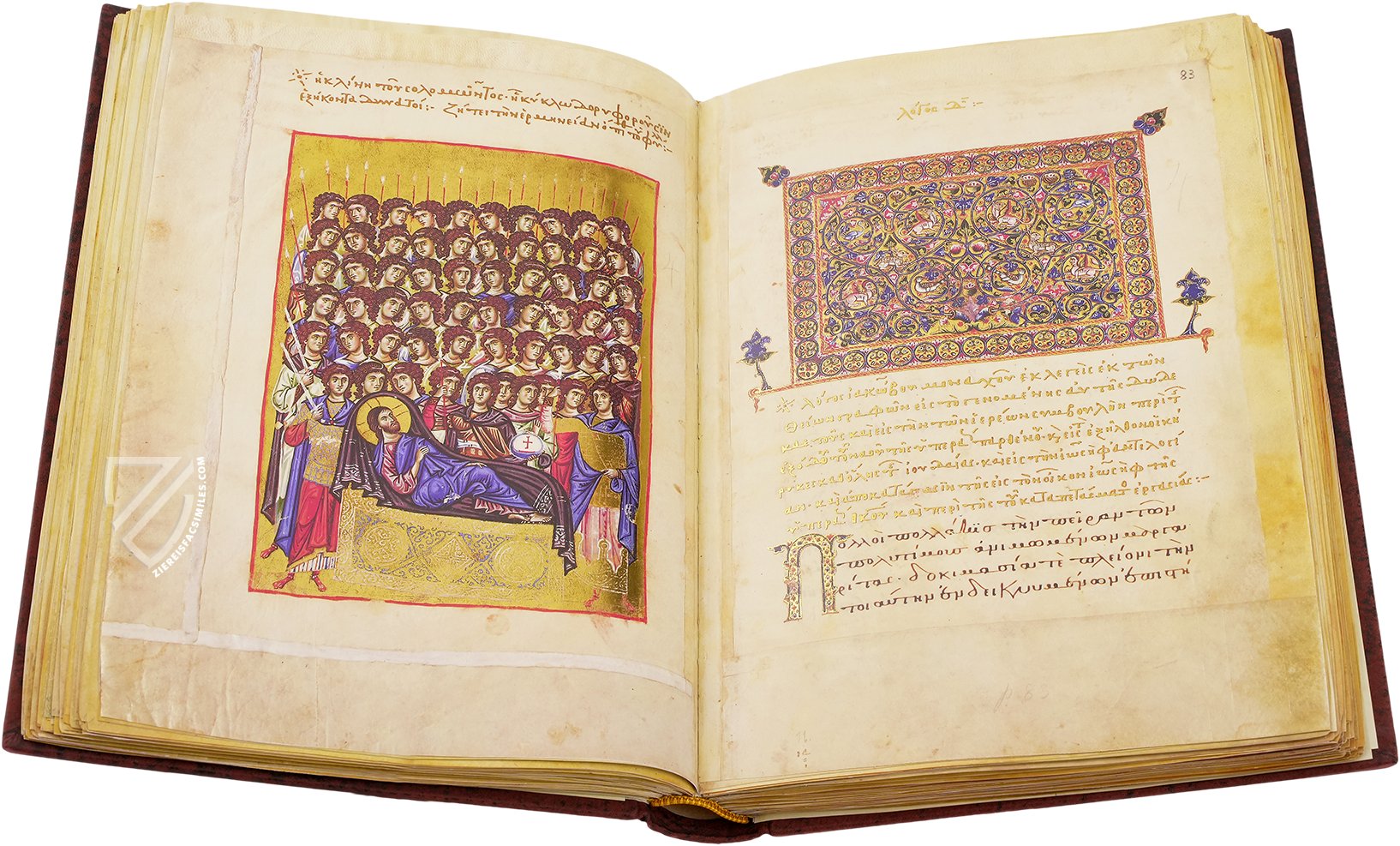

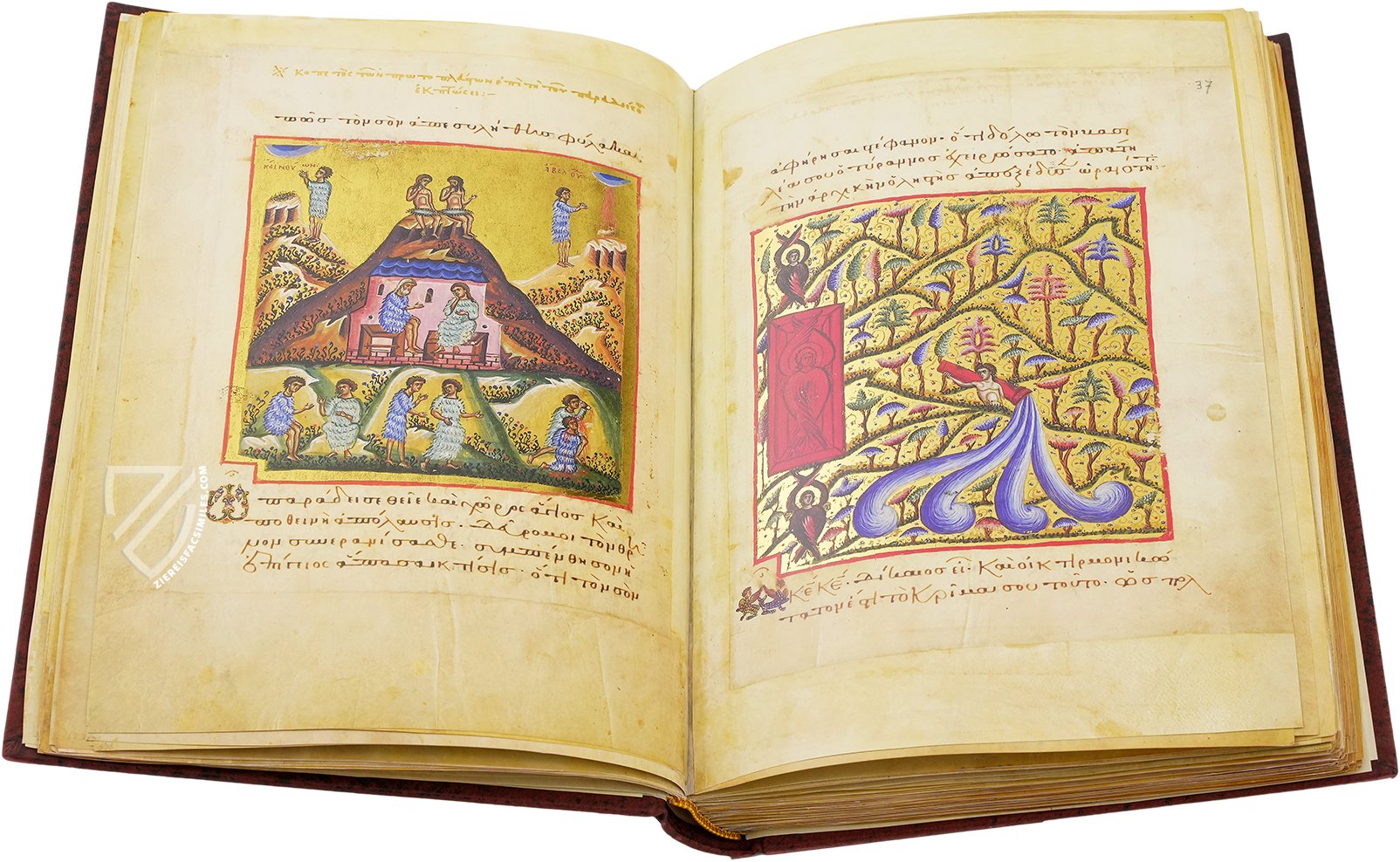

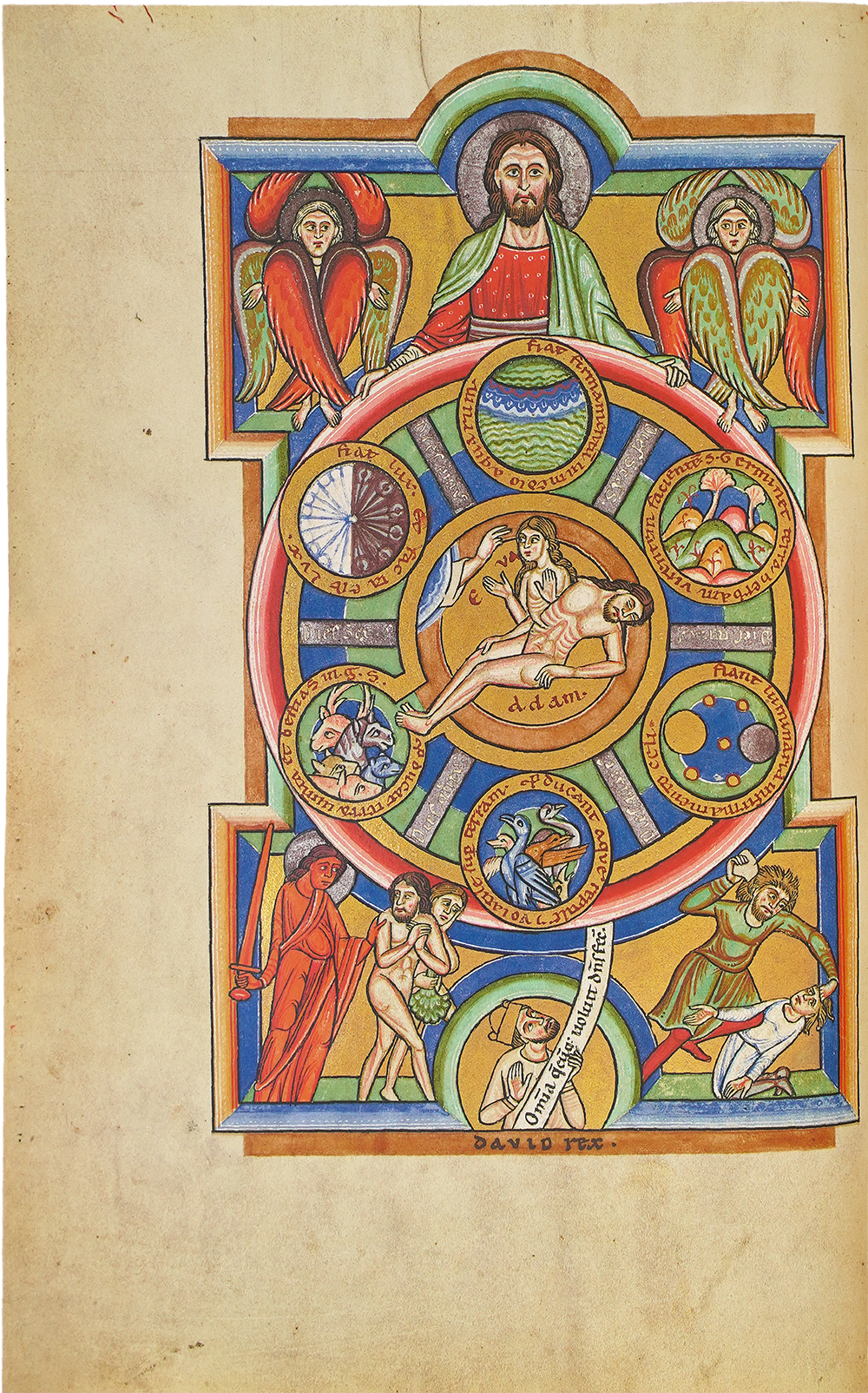

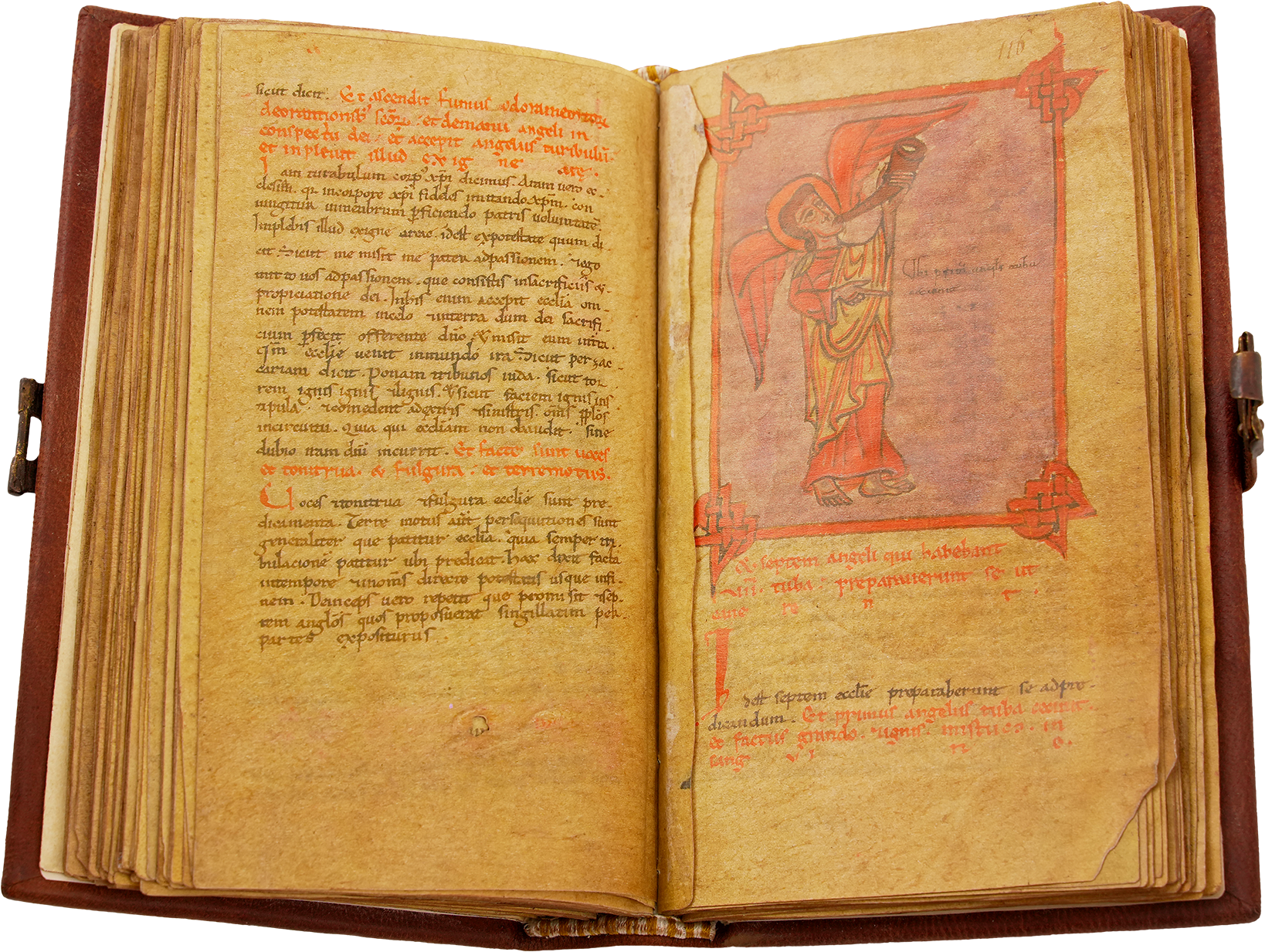

Byzantine Cultural Revival under the Komnenian Dynasty

In the course of the 12th century, the Komnenos made a concerted but ultimately unsuccessful effort to restore the Byzantine Empire’s military, territorial, economic, and political position to where it was before the disastrous Battle of Manzikert and the subsequent loss of most of Anatolia to the Seljuk Turks.

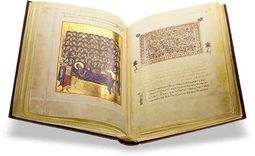

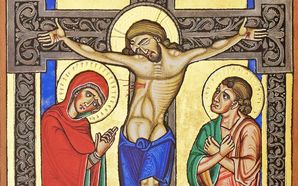

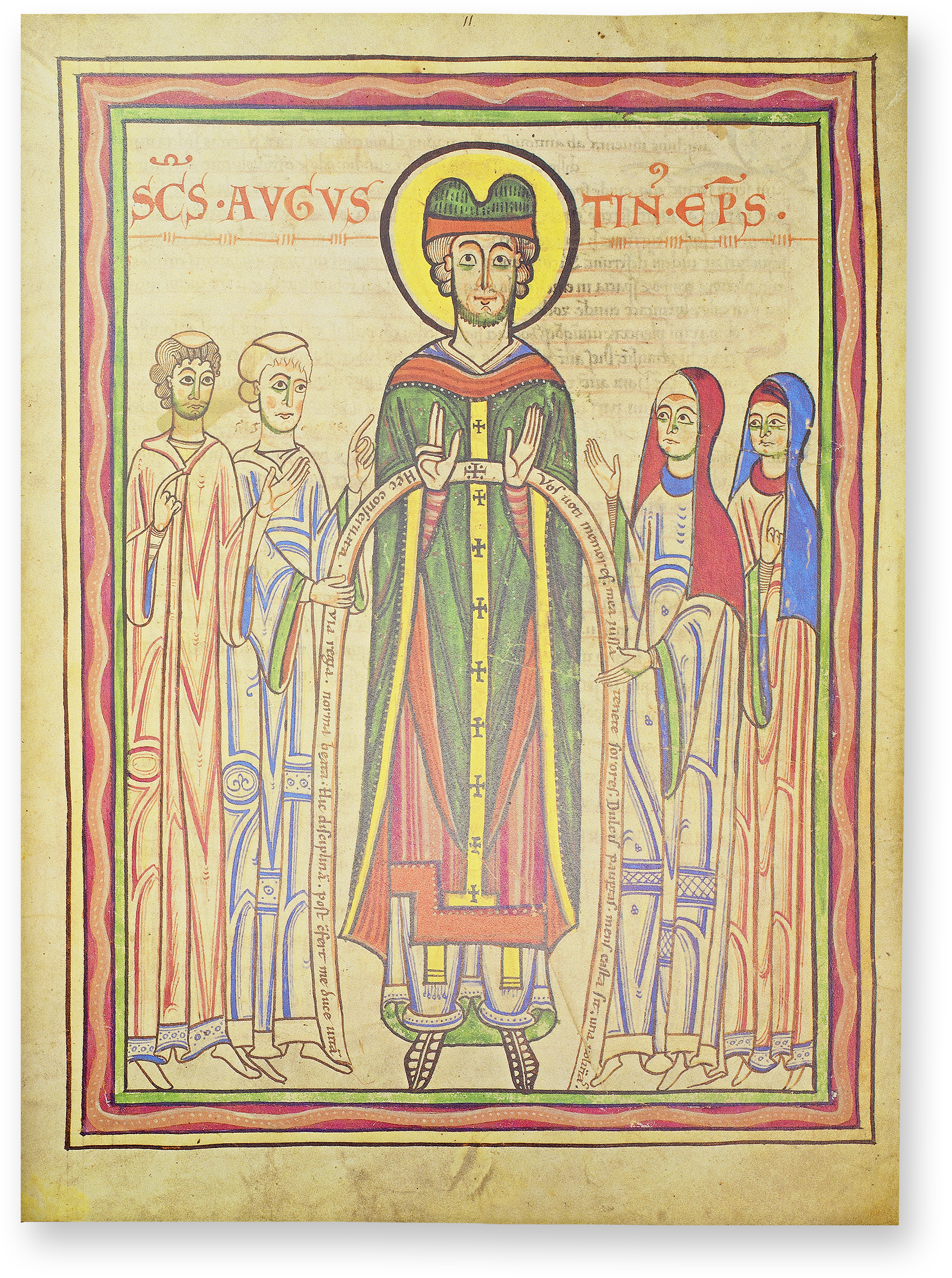

However, they were successful in restoring the prosperity and cultural output of the Byzantine Empire, and increased contact with the West, sharing their technology freely with the Latins. Manuscripts like the Marian Homilies made in the first half of the 12th century by Jakobos Kokkinobaphos in Constantinople, and the St. Peter Pericopes from Salzburg, which blends Byzantine principles of style with visual themes from western examples, attest to the ongoing artistic and cultural relevance the Byzantines. They also enjoyed a Renaissance of interest in classical authors that would eventually spread to the West.

However, during this time the Byzantines fought continuously with the Normans. They eventually lost their Italian possessions to the Normans, who also attacked them in their Grecian and Thracian heartland repeatedly throughout the period. In spite of a defeat at the Battle of Myriokephalon in 1176 that ended Byzantine efforts to reconquer the whole of Anatolia from the Turks, the army remained strong, its positon in western Anatolia was secure, and they regained control of the northern and southern coasts, including Cilicia and Antioch.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The Terminal Decline of the Byzantines

Although commissioning the Crusades initially appeared to be a balm for relations between Orthodox and Catholic peoples, it eventually only furthered the complications and distrust between them: the Byzantines feared the large and unruly hosts that arose out of the West, who were in turn wary of the treachery of the Byzantines because they cooperated with the Turks when it suited them.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

This tension boiled over in April of 1182 after the death of Emperor Manuel I in 1180 when his widow, the Latin princess Maria of Antioch, acted as regent to their infant son. The citizens of Constantinople had long been resentful of the Italian merchants in the city, who now numbered 60,000, and believed that favorable conditions given them by the authorities allowed them to dominate trade in the city. The regency of this Latin princess was the last straw, and the citizenry of Constantinople turned against the Italians in the city in a riot that has come to be known as the Massacre of the Latins. Although many sensed trouble was coming and had taken to sea, most of the Latin population was mercilessly slaughtered without distinction for women or children.

Although trade relations were soon restored, trust never was and the incident only confirmed western suspicions of the treacherous and duplicitous nature of the Byzantines. No objections were raised in the West when a Norman expedition under William II sacked Thessalonica, the Empire's second largest city, in 1185. The citizens of Constantinople would themselves be punished two decades later when the so-called Latins returned – their vengeance would begin the irreversible decline of the Byzantine Empire.

Experience more