The Tomb of Christ - The Mystery of the Resurrection in Medieval Illumination

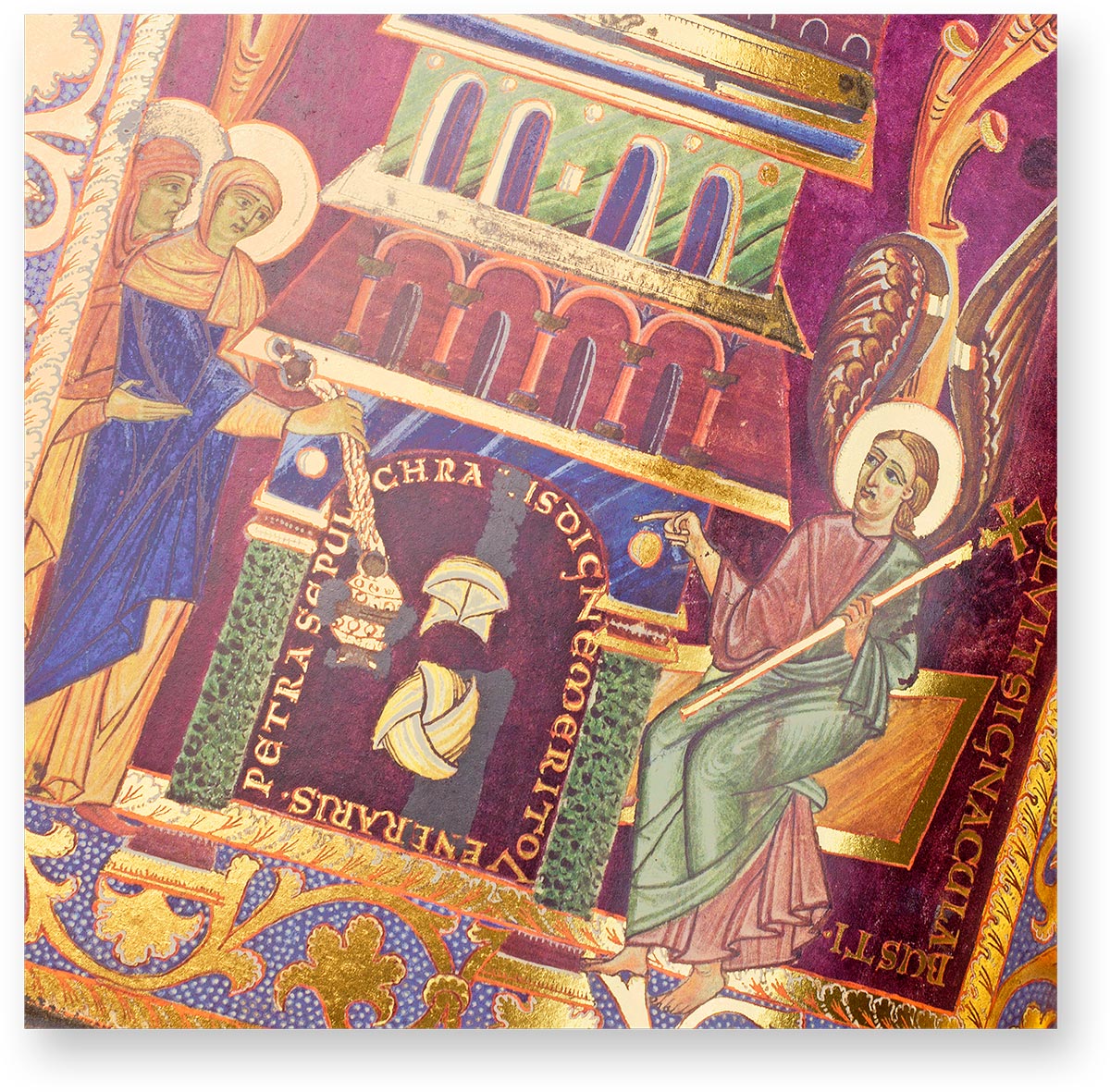

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem is probably one of the most famous sacral buildings in the world and, as the central pilgrimage site of Christianity, attracts millions of believers and interested people every year – given that it houses the Golgotha rock and the Holy Sepulcher, where Jesus Christ is said to have been buried after his crucifixion. As early as the 4th century, Constantine the Great had the structure built as a place of worship, creating an architecture that would shape the concept of the Holy Sepulcher for centuries: even today, the burial chamber is enclosed by a chapel-like aedicule, which in turn is located within the Dome of the Anastasis.

The veneration of the tomb and the mystery of the resurrection is already evident in the Middle Ages not only in a flourishing pilgrimage system and the extensive trade in relics, but as a result especially in countless chapels imitating the Holy Sepulchre, such as the so-called Holy Sepulchre in Görlitz, which were intended to allow the holy site to be physically tangible in other places as well. Moreover, the feast of the Resurrection, Easter, is the most important religious event of the Christian year.

To the facsimile

The Holy Sepulchre in Book Illumination

However, the stories surrounding the tomb of Christ were also a popular and important, if not so visible, theme in book painting. After all, the empty tomb is one of the greatest mysteries of the biblical stories, which occupied countless Christian scholars. How could one imagine the process of resurrection? And what evidence could be brought to bear on it?

As a reminder, the Gospels, as well as some apocryphal writings, tell us that after the crucifixion Jesus' body was buried in a rock tomb sealed with a large, heavy stone. As previously announced, Christ's resurrection occurred three days after the burial, whereupon various people close to him found the tomb empty. In the 40 days that followed, the resurrected Christ appeared again and again to his followers, before finally ascending to heaven.

For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale's belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth. (Mt. 12,40)

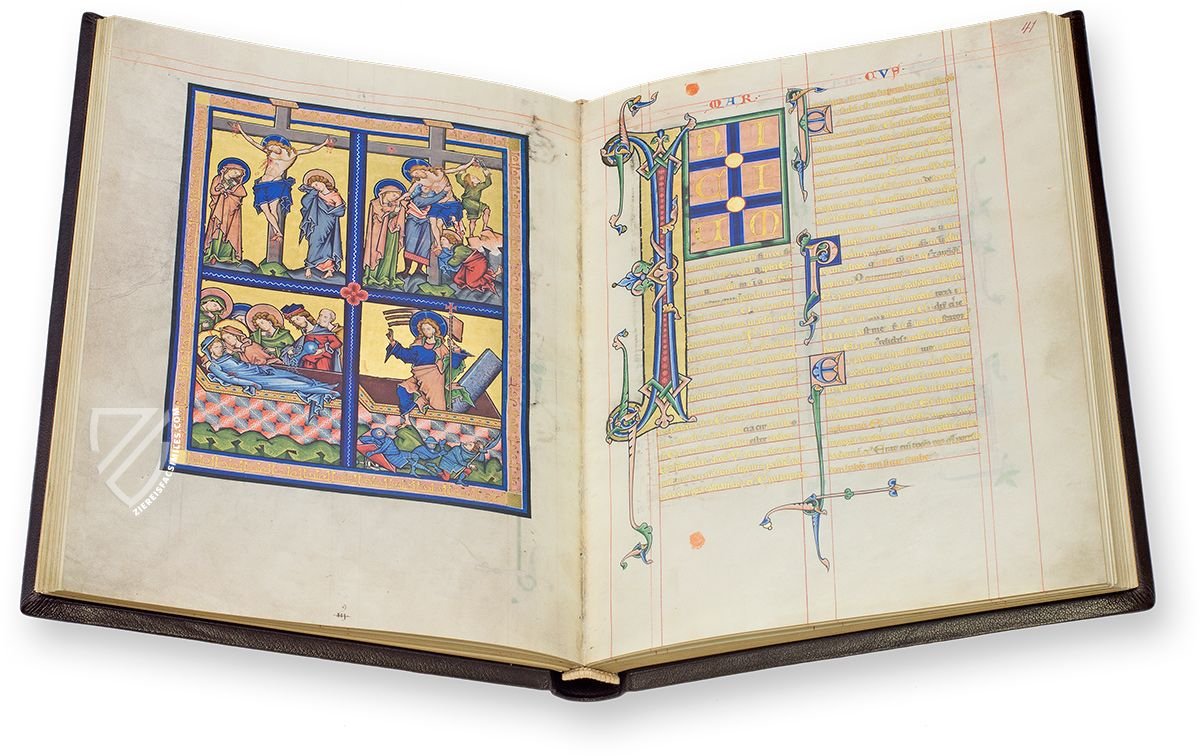

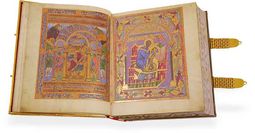

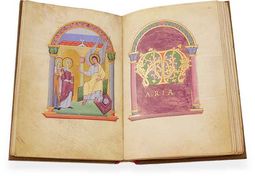

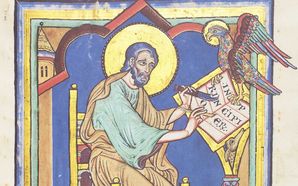

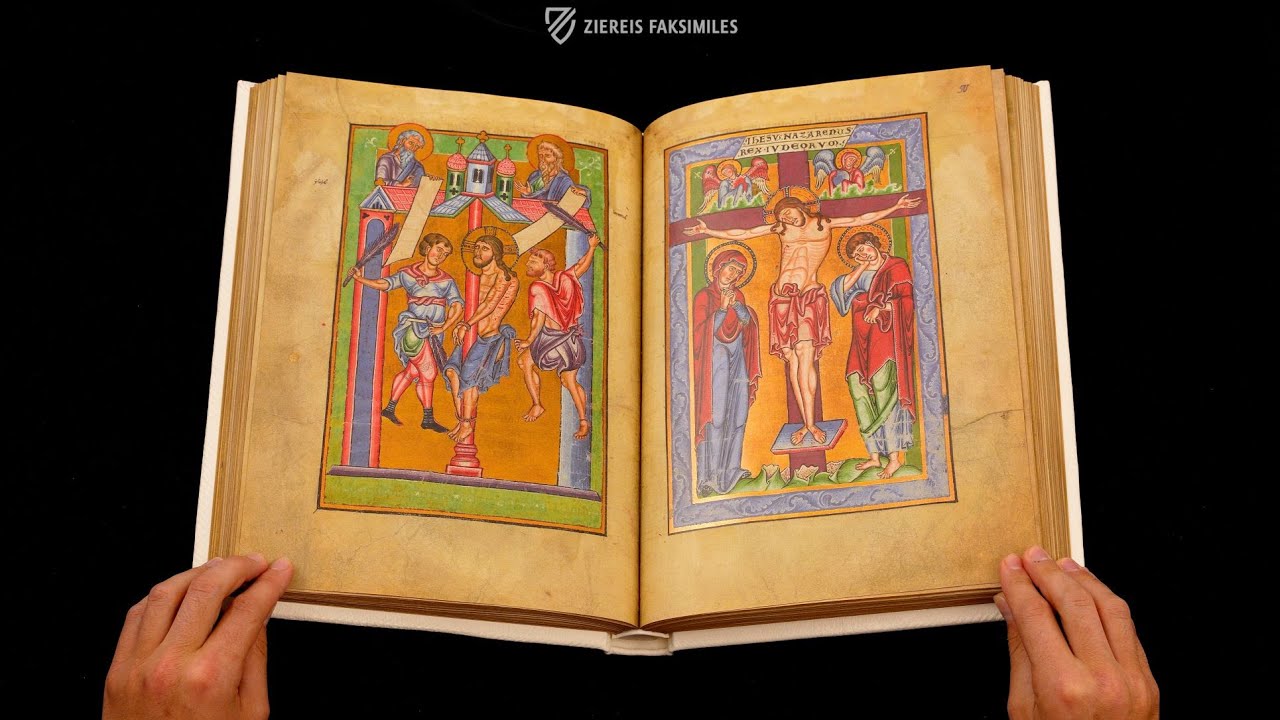

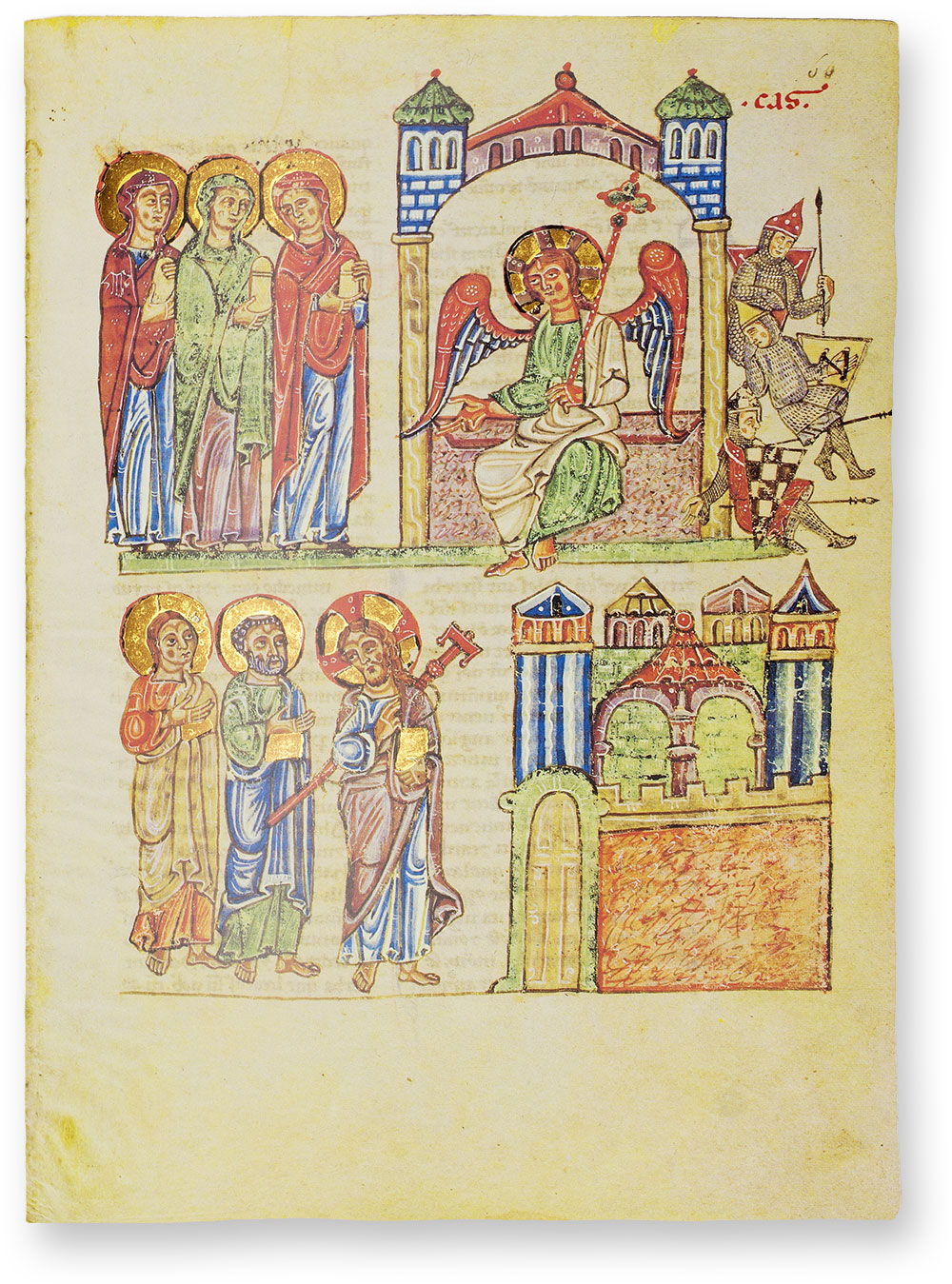

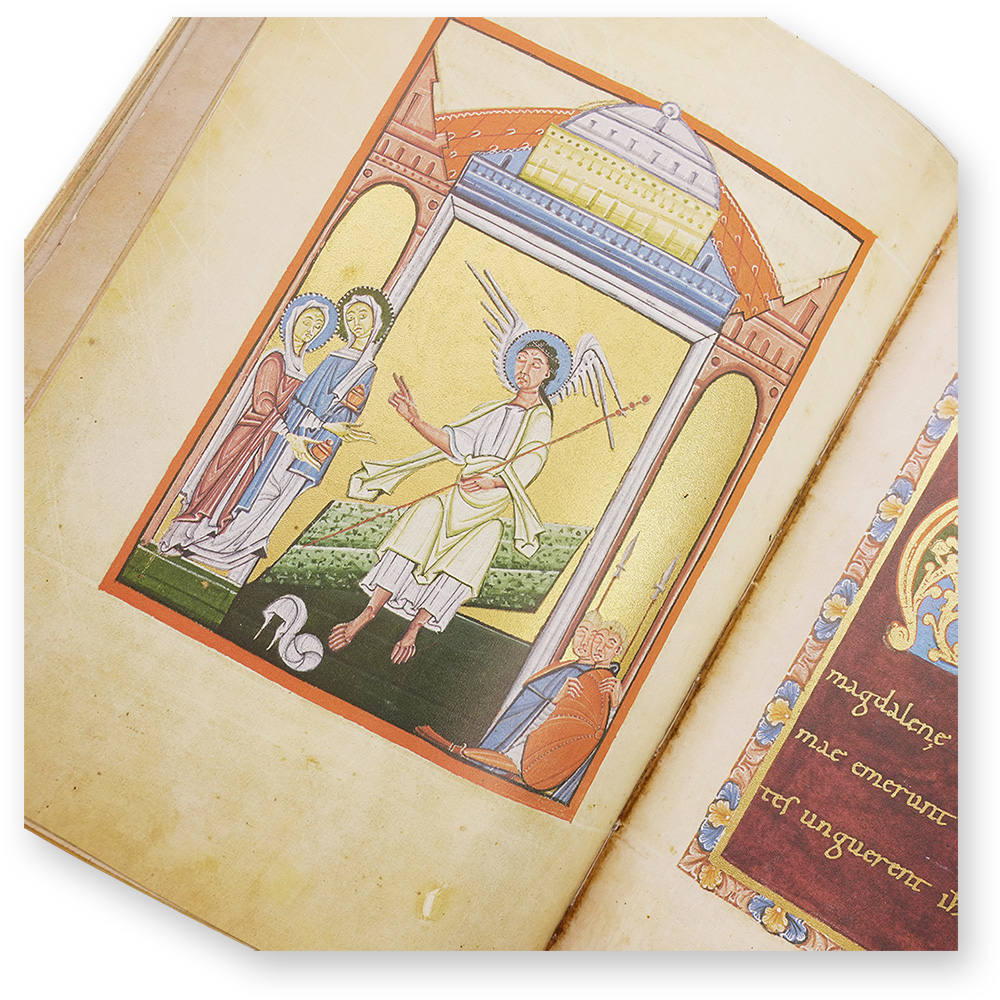

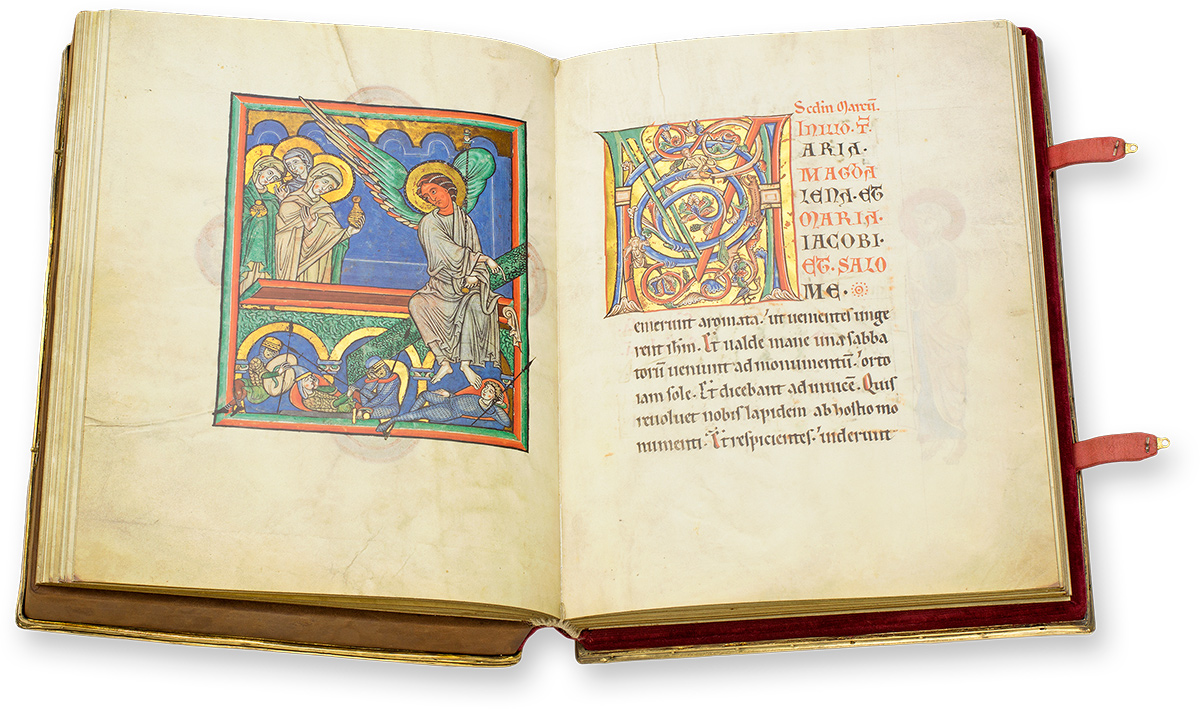

In the course of the Middle Ages, illuminators found different solutions to bring the key moment of the Resurrection into the image, which must have been quite a challenge, since a moment was to be depicted for which there were no descriptions due to the lack of eyewitnesses. Thus, at first the empty tomb itself became the central theme of the picture, accompanied by the two or three Marys who find there the angel who tells them about the Resurrection. While here the mystery is emphasized by the absence of Christ, later illuminators decided to show the mysterious event itself and thus accentuated Christ's victory over death.

To the facsimile

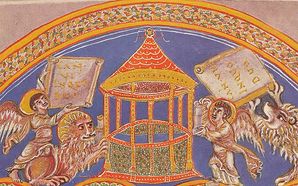

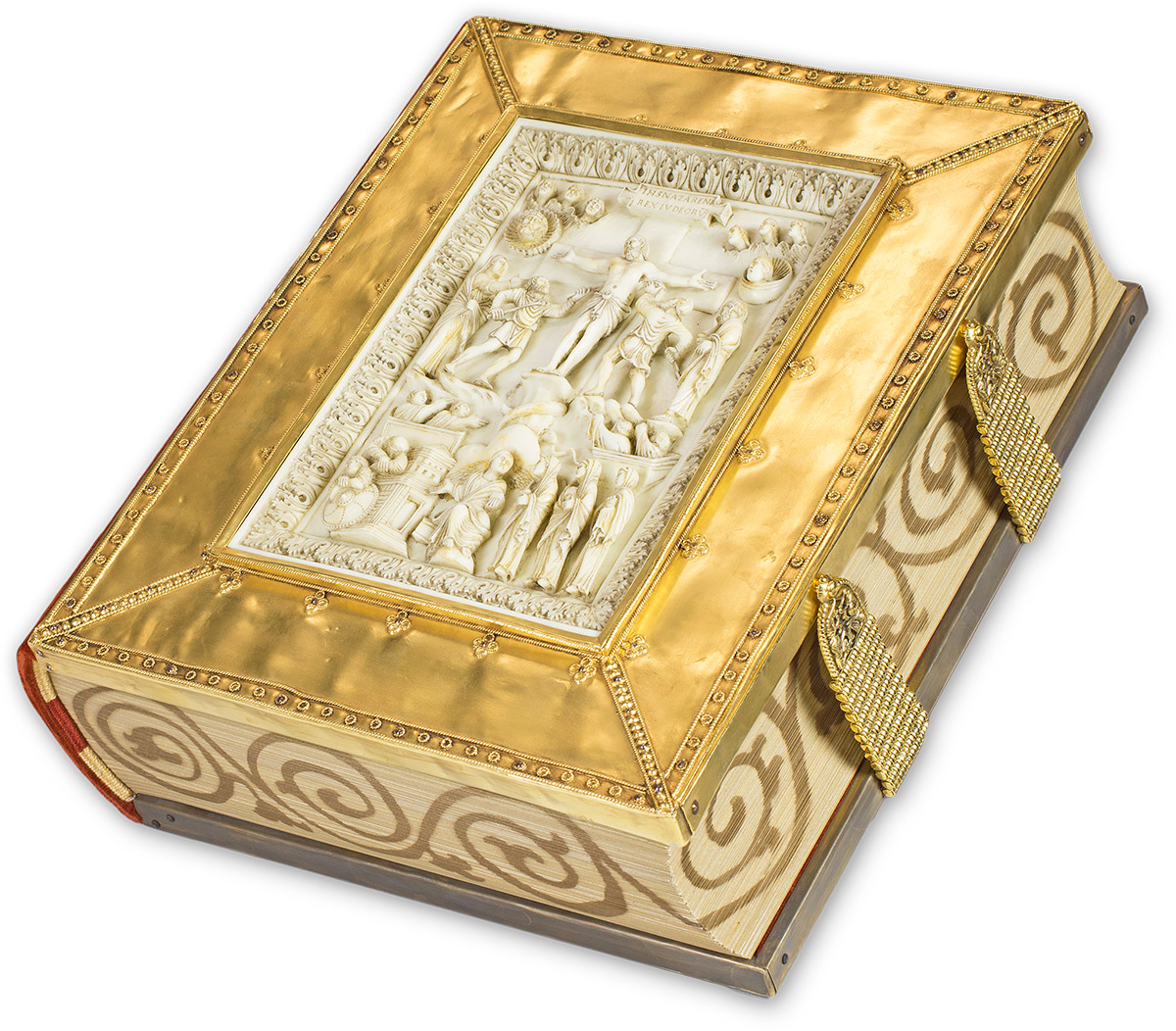

A Mausoleum for Christ

The famous Reidersche Tafel (around 400 AD) shows the earliest representation of the tomb: On the left side rises a tower-like mausoleum of late antique forms. On a rectangular pedestal rests a round aedicula with filigree double columns – a reminiscence of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, which was already architecturally enclosed around the time this ivory panel was created. In front of the tomb, an angel sits on some rocks, stretching his hand with a orator's gesture towards the three Marys approaching from the right. Remarkably, the door to the burial chamber is locked – so the women must trust the word of the angel.

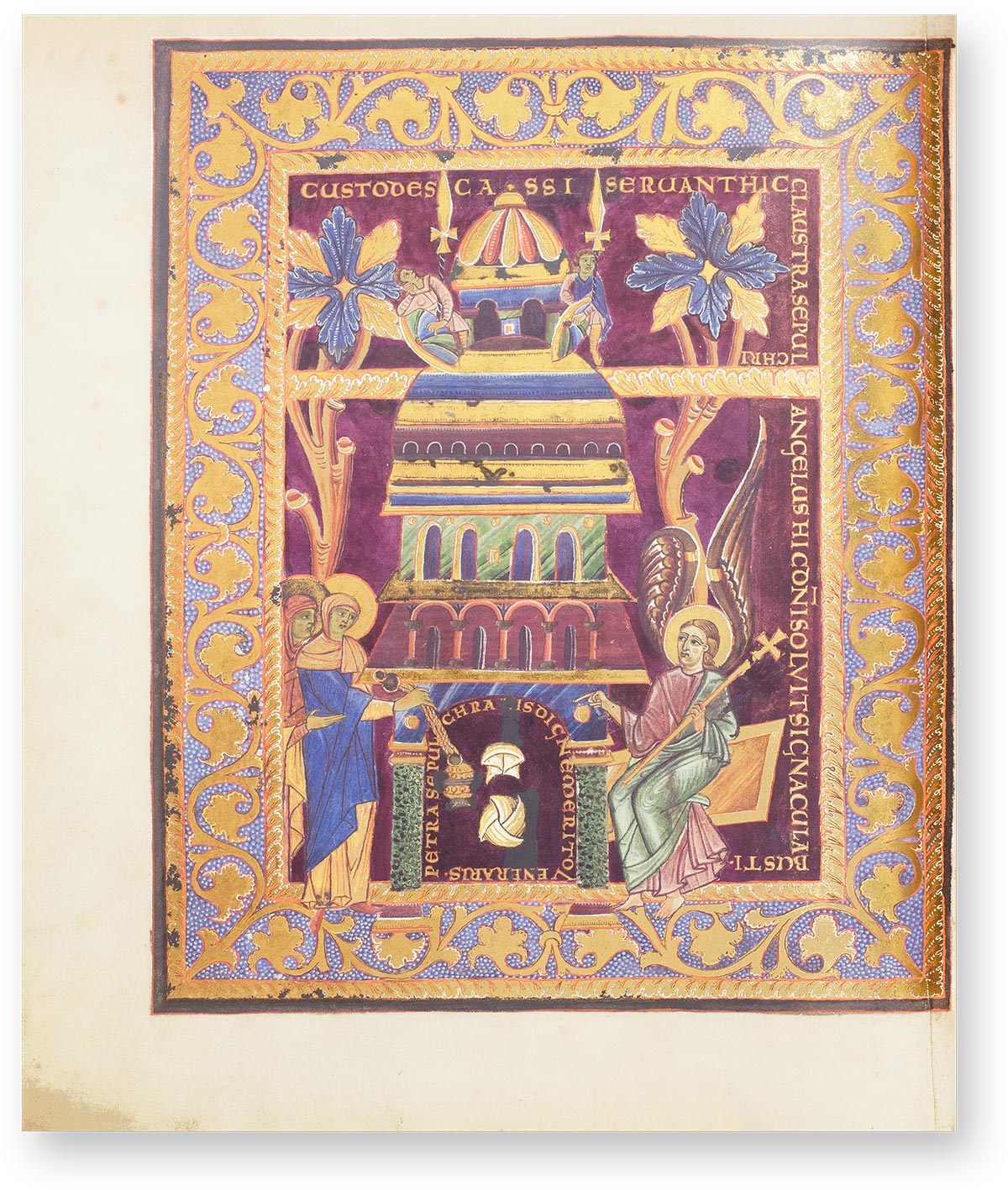

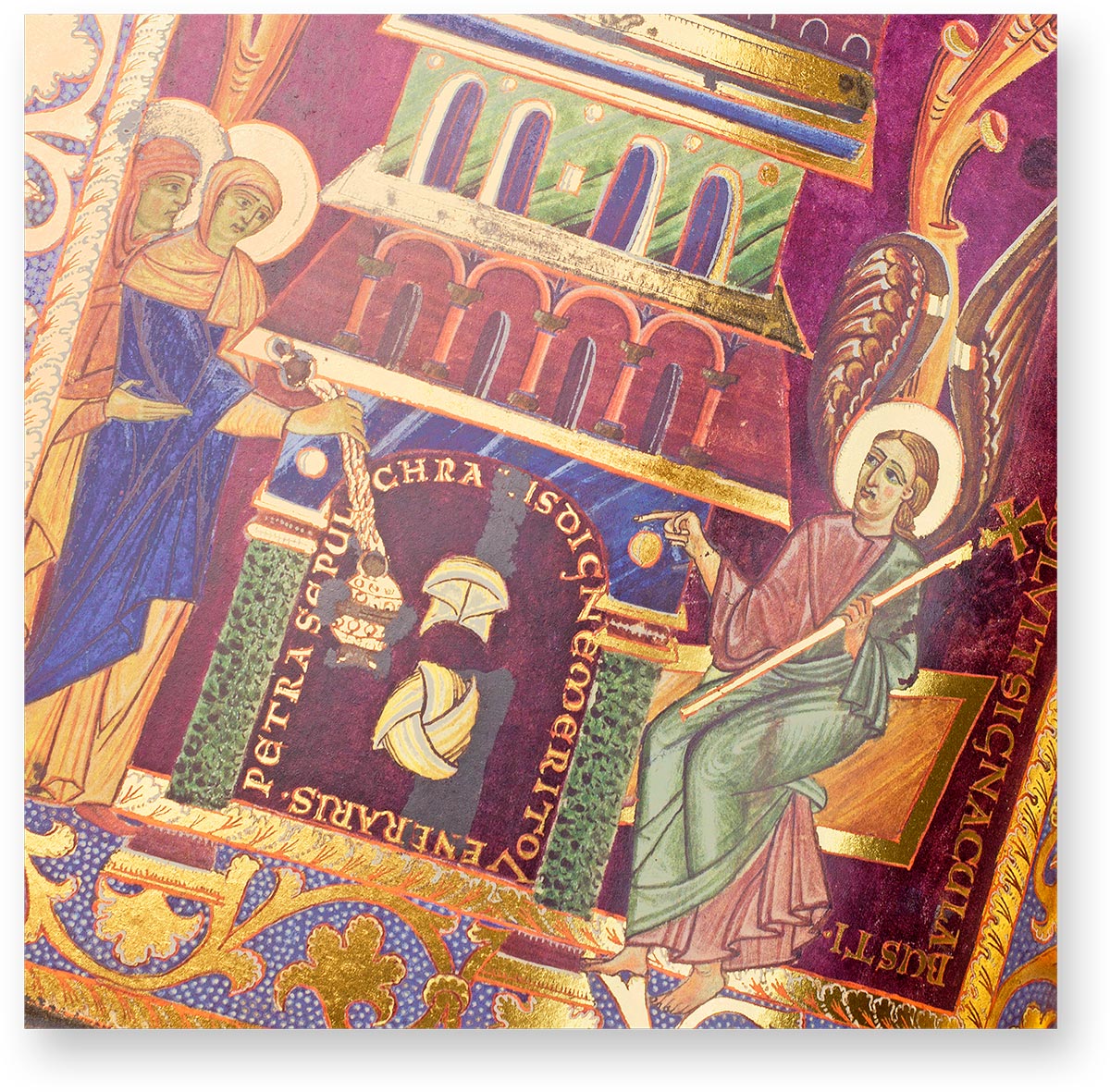

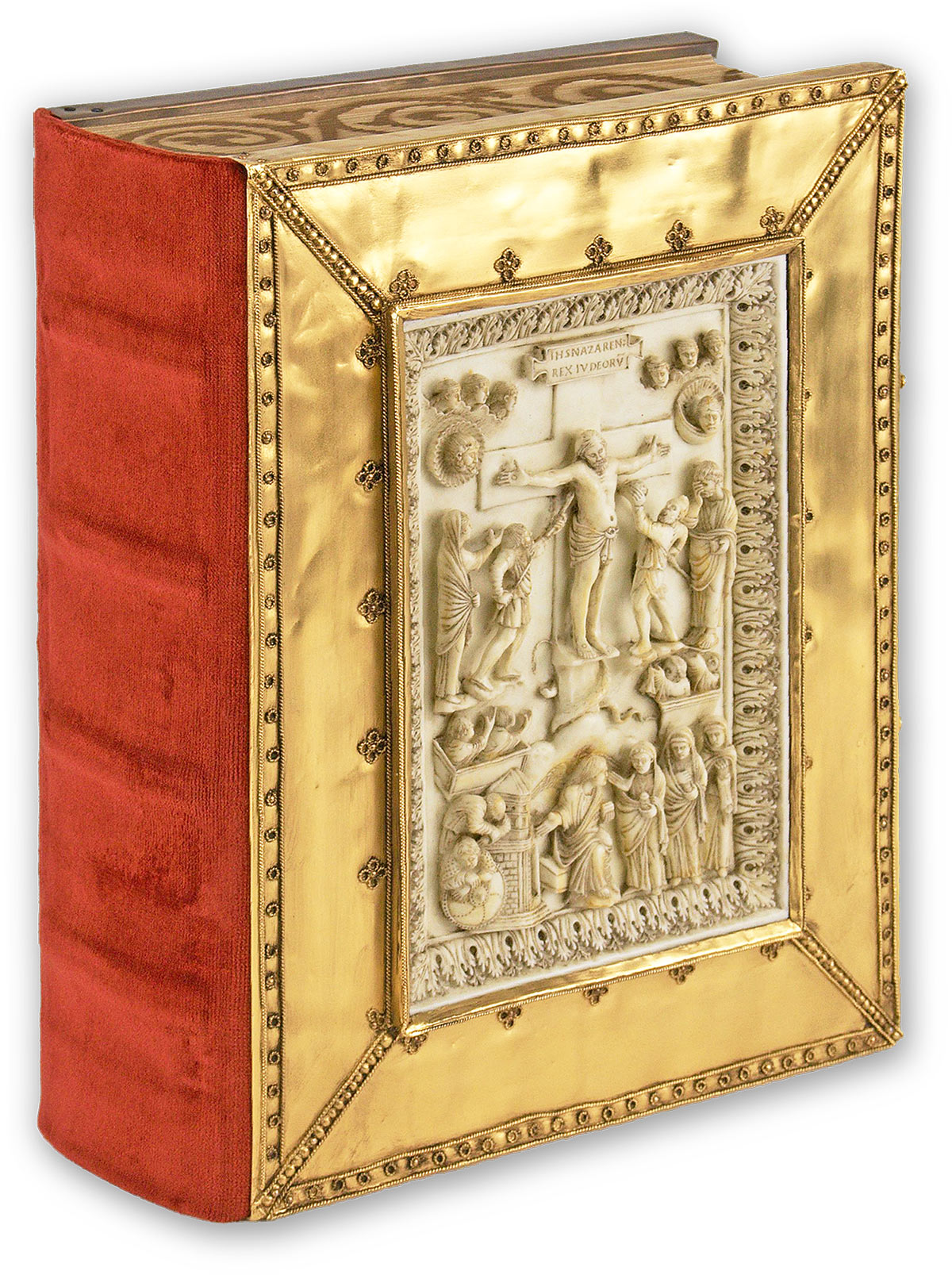

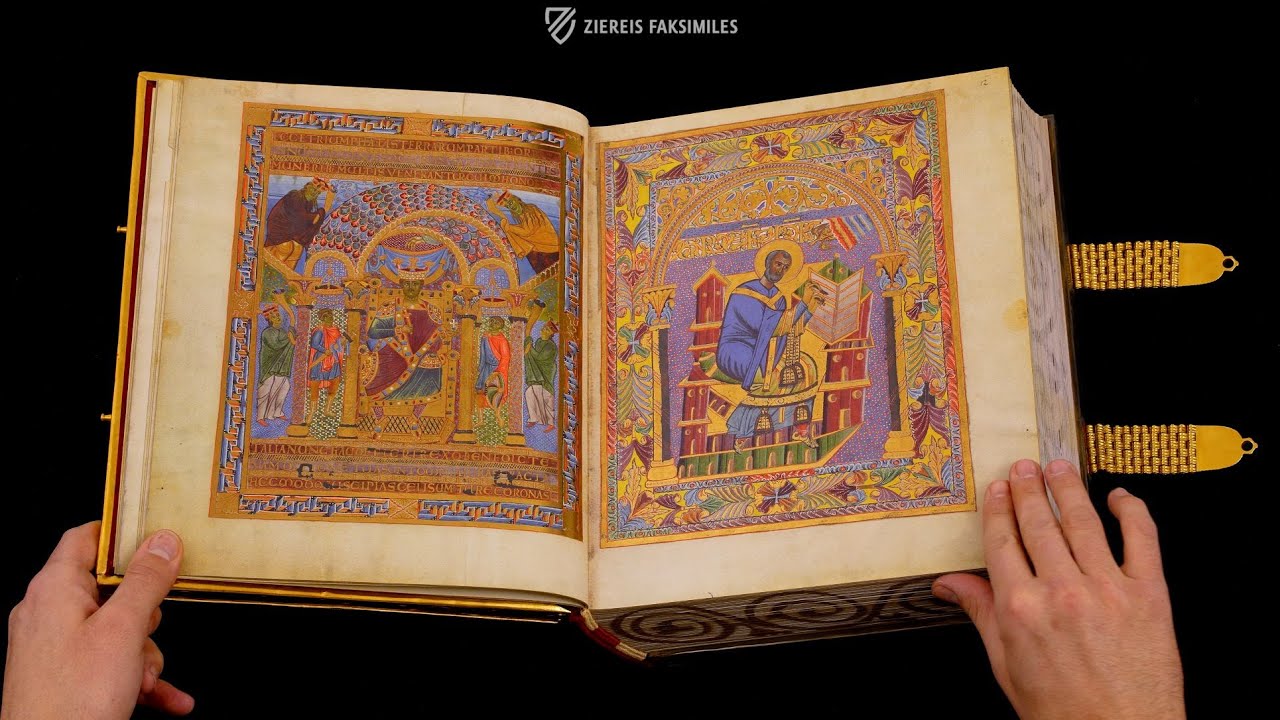

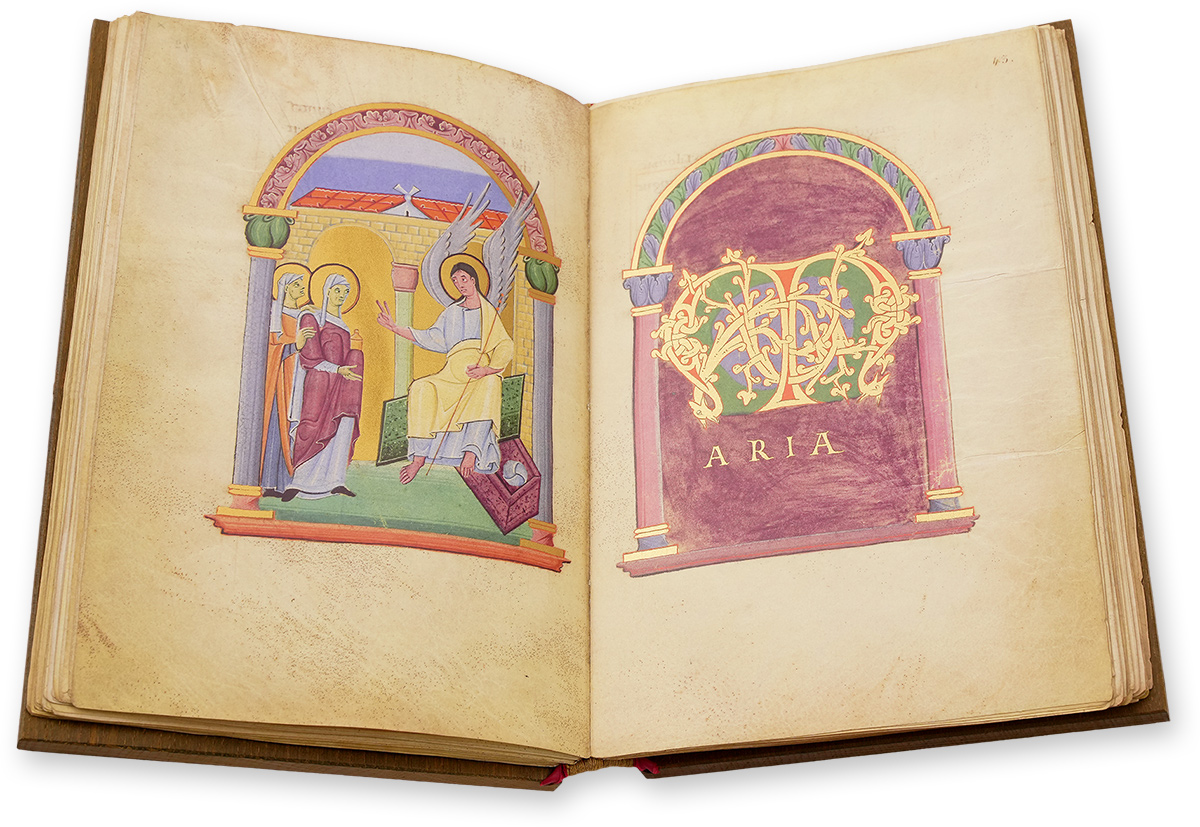

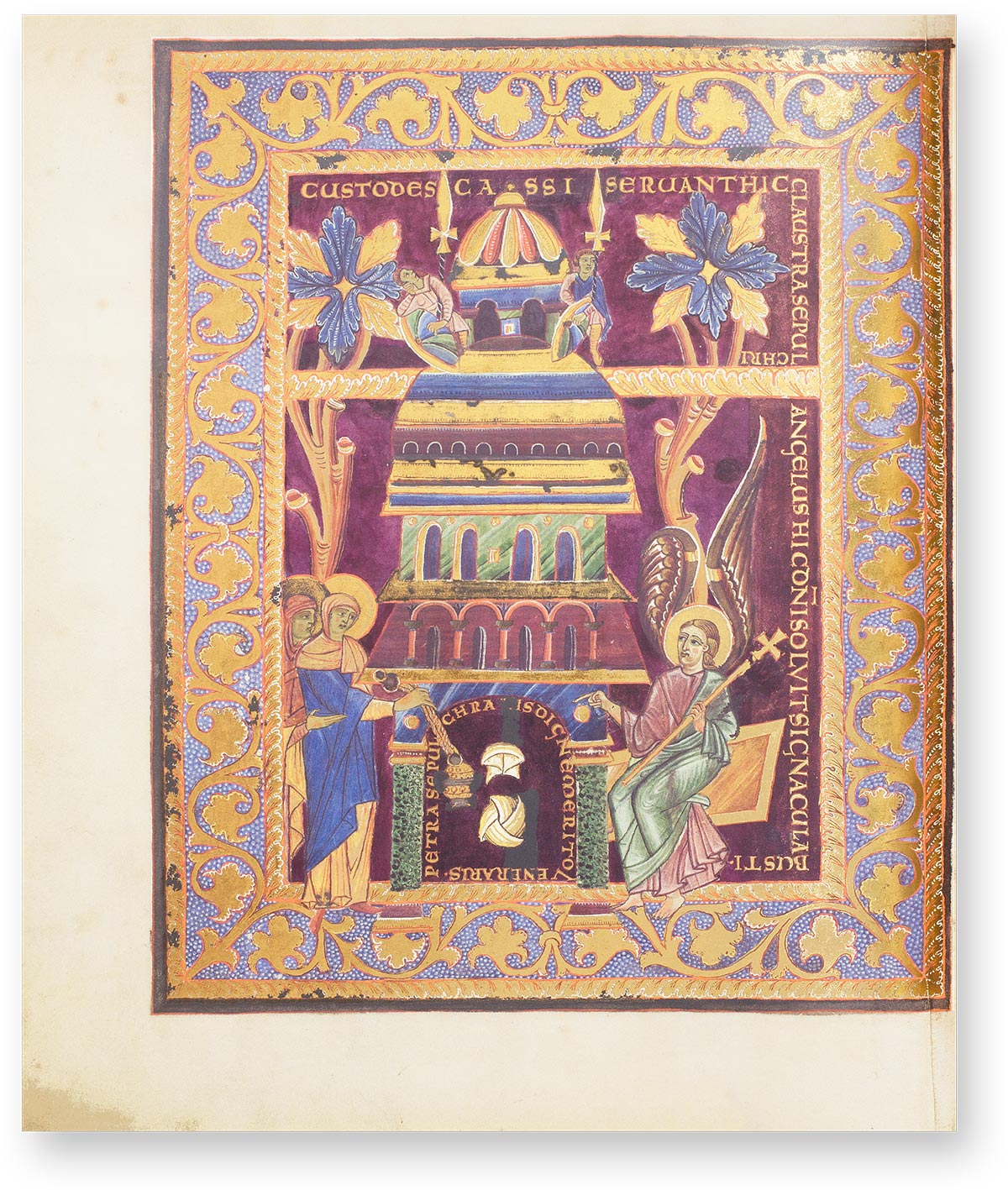

Things are different in the Sacramentary of Henry II: although both the full-page miniature and the ivory panel of the book cover also show the tomb of Christ in an exterior view as a tower-like mausoleum, here the angel explicitly points to the open tomb, whose yawning emptiness is eye-catching. In the dark entrance of the peculiarly layered painted architecture hover only two parts of the shrouds of Christ.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

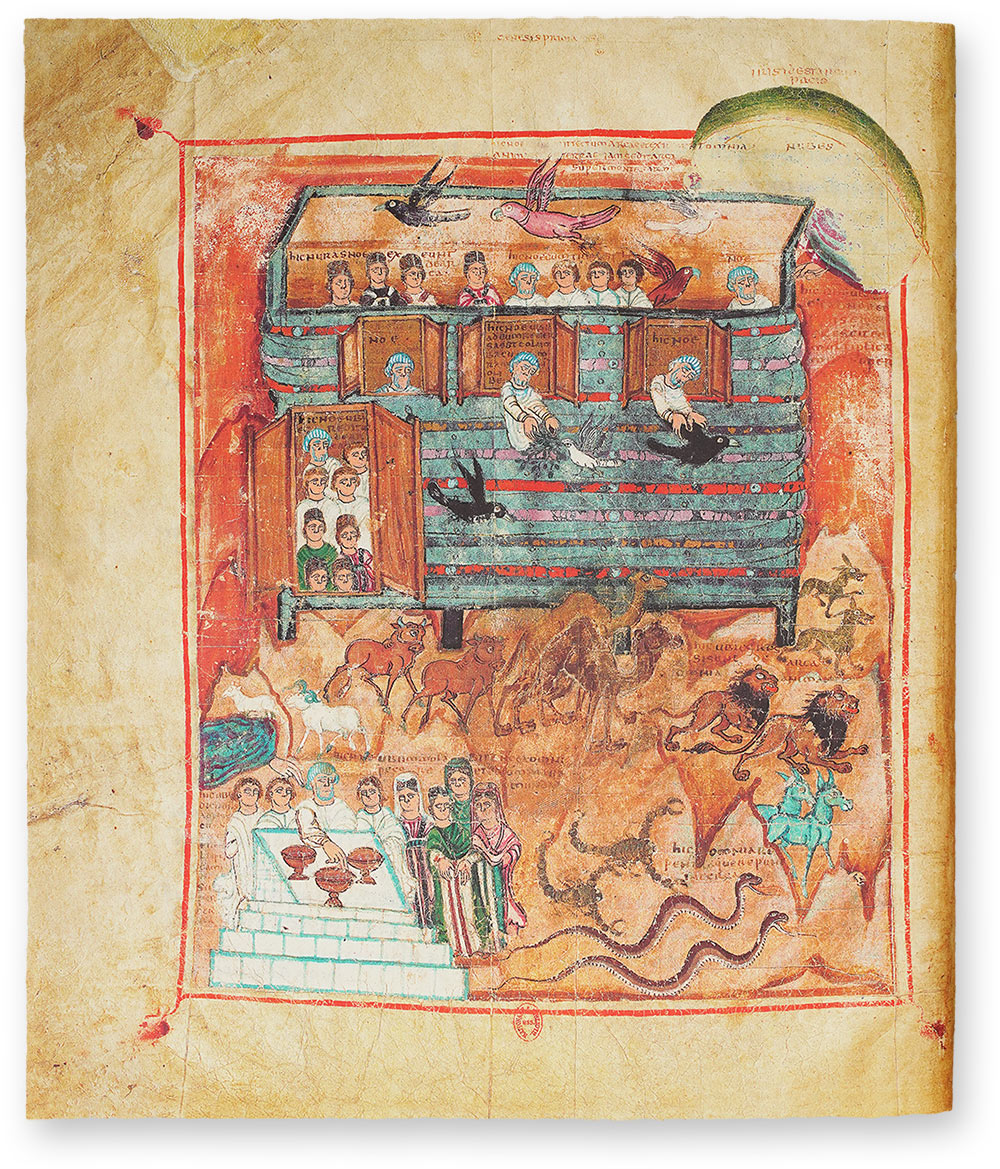

It is astonishing that even the early book painting seems to be oriented more to the pilgrimage site in Jerusalem than to the biblical descriptions. The detailed and magnificent mausoleums do not correspond in the least to the Gospels, which all speak of a rock tomb:

And [Joseph] took it down, and wrapped it in linen, and laid it in a sepulchre that was hewn in stone, wherein never man before was laid. (Lk. 23,53)

Nevertheless, this pictorial tradition can be found in various artistic testimonies until the 13th century. From about 1000, however, another variant predominates: the sarcophagus.

Experience more

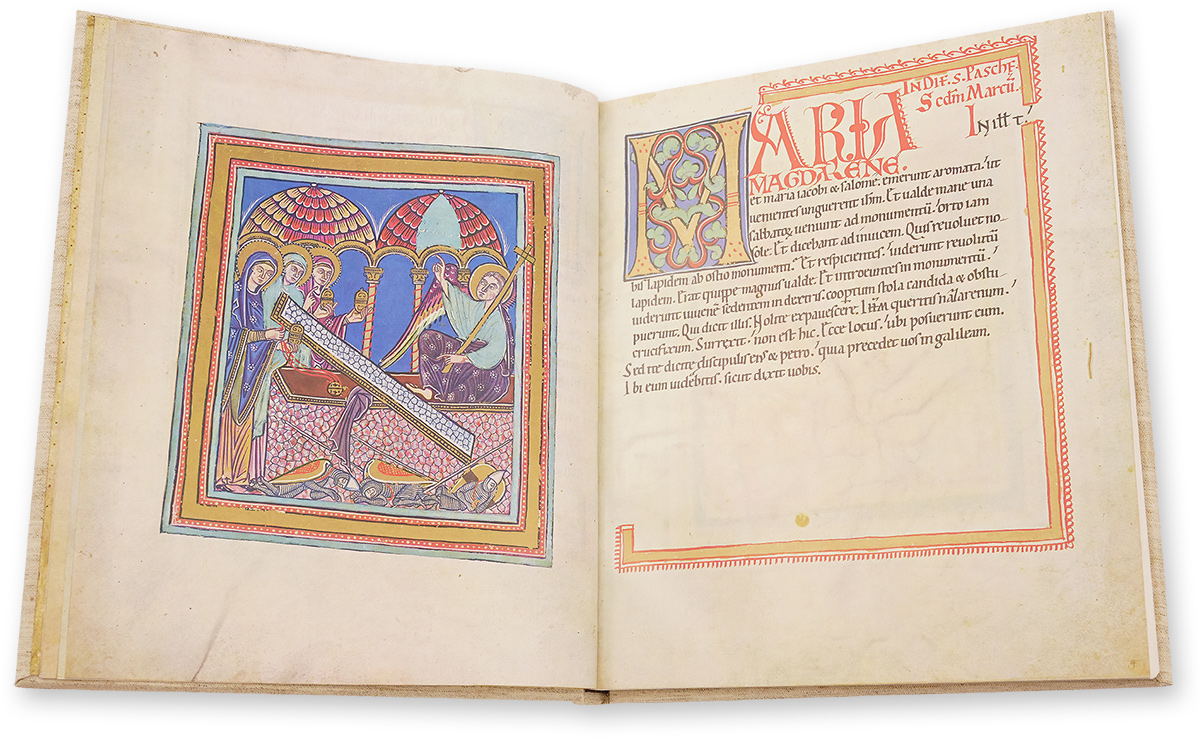

The Tomb of Christ as Sarcophagus

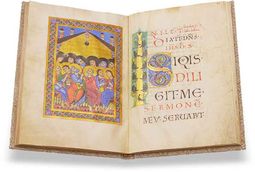

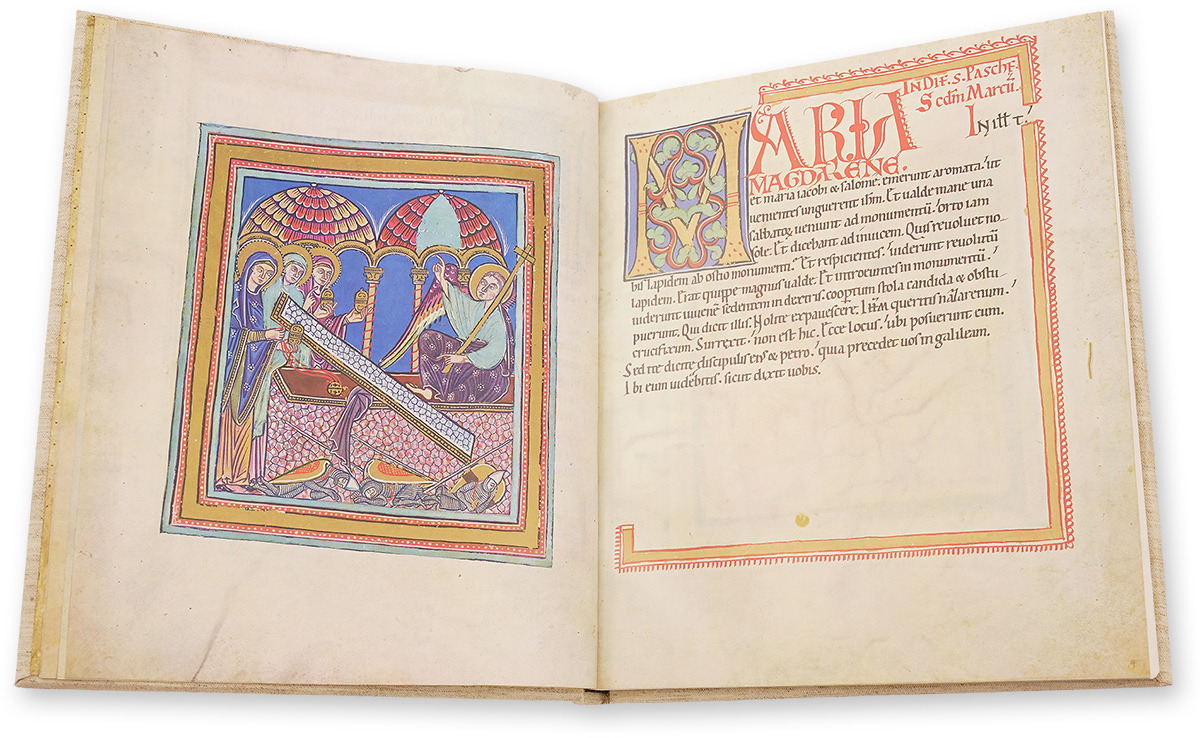

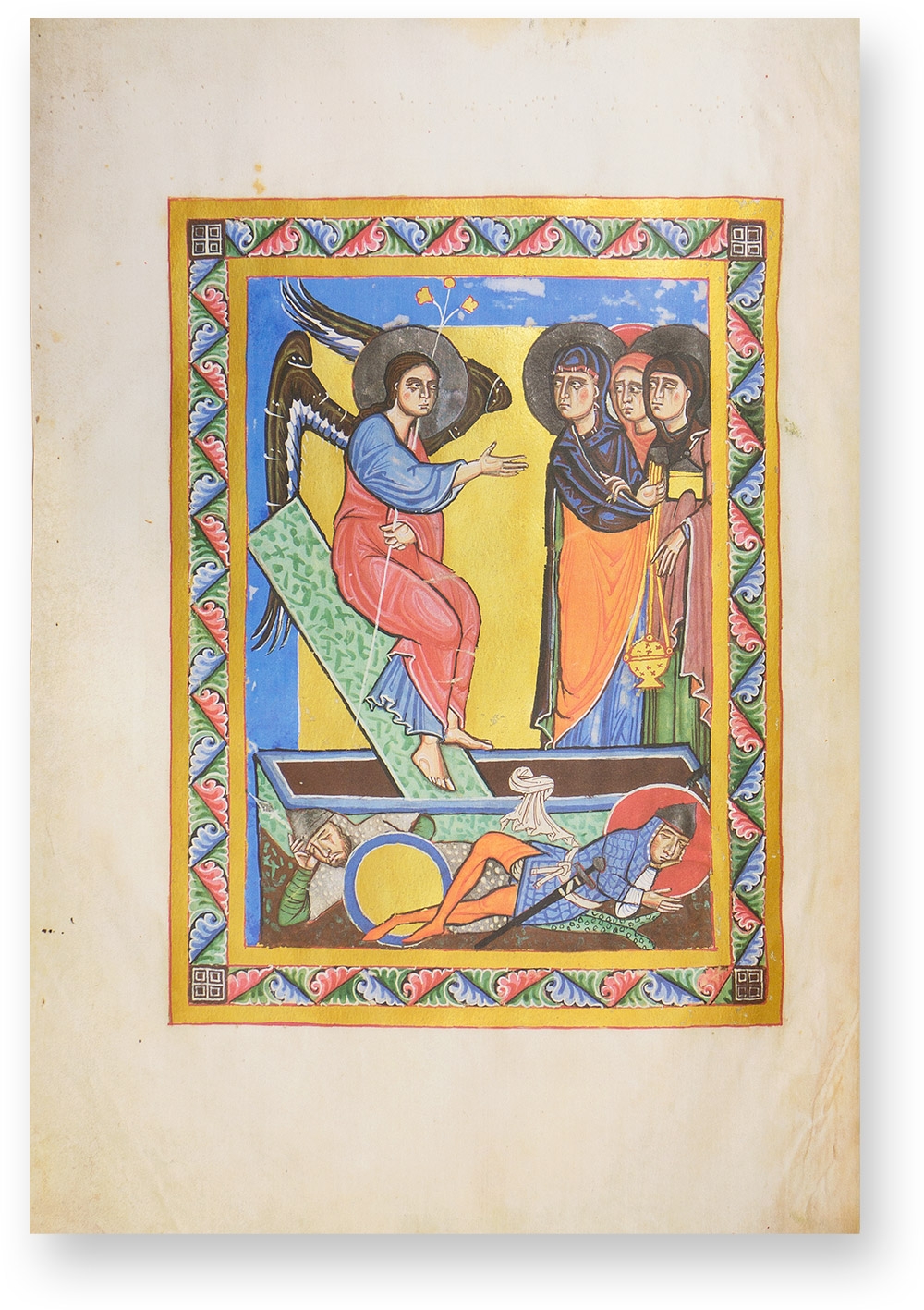

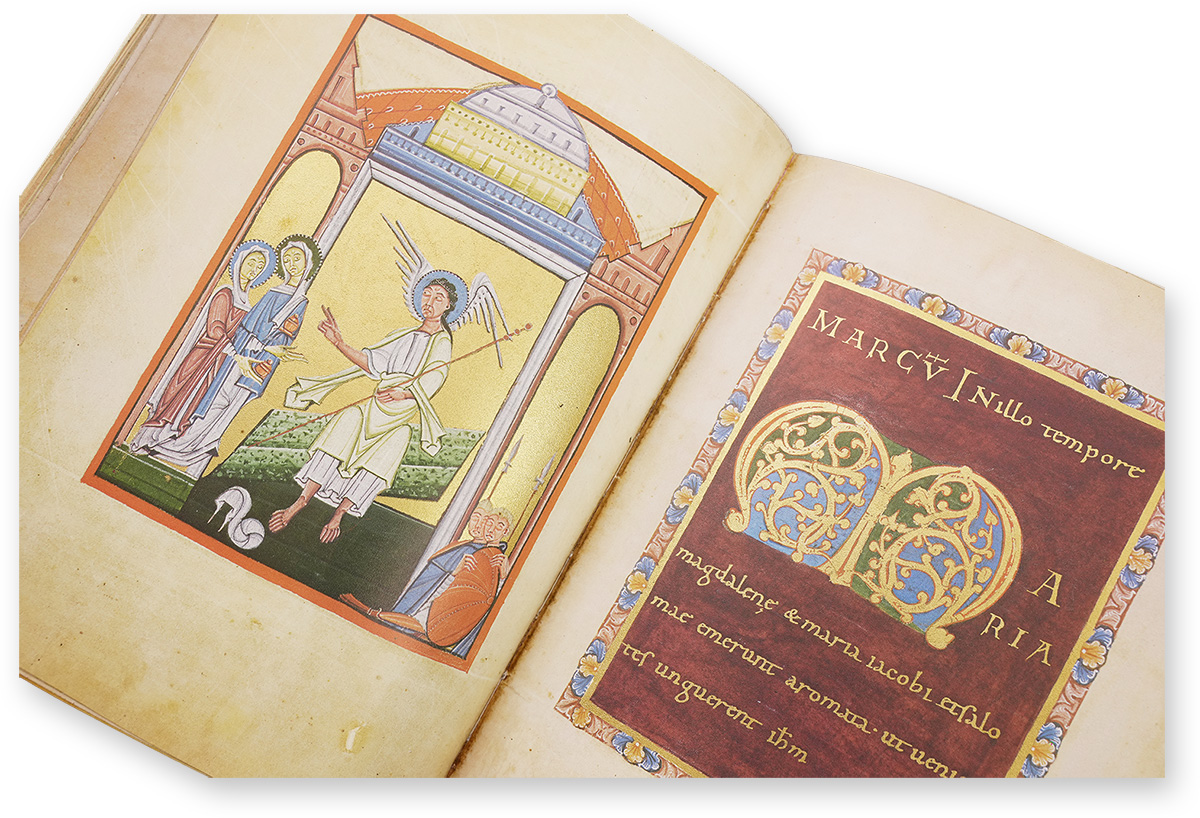

Pictures showing the tomb as a rectangular, stone sarcophagus often give us a glimpse of the interior of the peculiar mausoleums. By arranging the Marys and the angel in front of ornate pillared arcades with rounded arches, they often remain attached to the traditional, detailed architecture. What is new, however, is that the angel sits on an empty sarcophagus while informing the women of what has happened. The lid of the tomb is thereby strangely displaced, especially in earlier works such as the Gospel Harmony of Eusebius and the Reichenau Pericopes Book, to reveal a view of the void - an interpretation of the stone being rolled away. Both the tomb and the angel seem to be devoid of any physical laws. Rather, they hover as remaining artifacts of the miraculous event in front of mostly golden backgrounds, which also suggest that something divine has occurred here.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

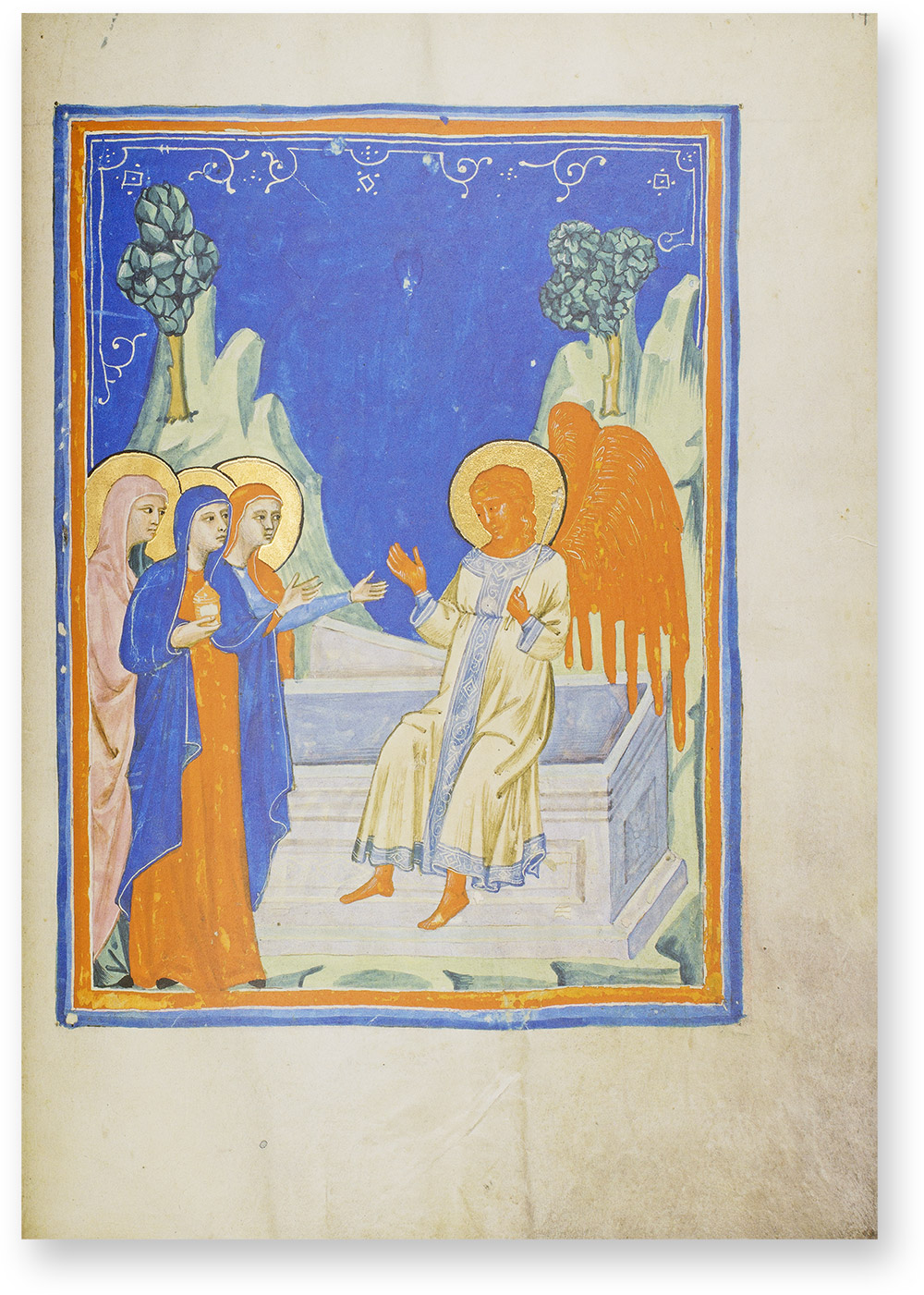

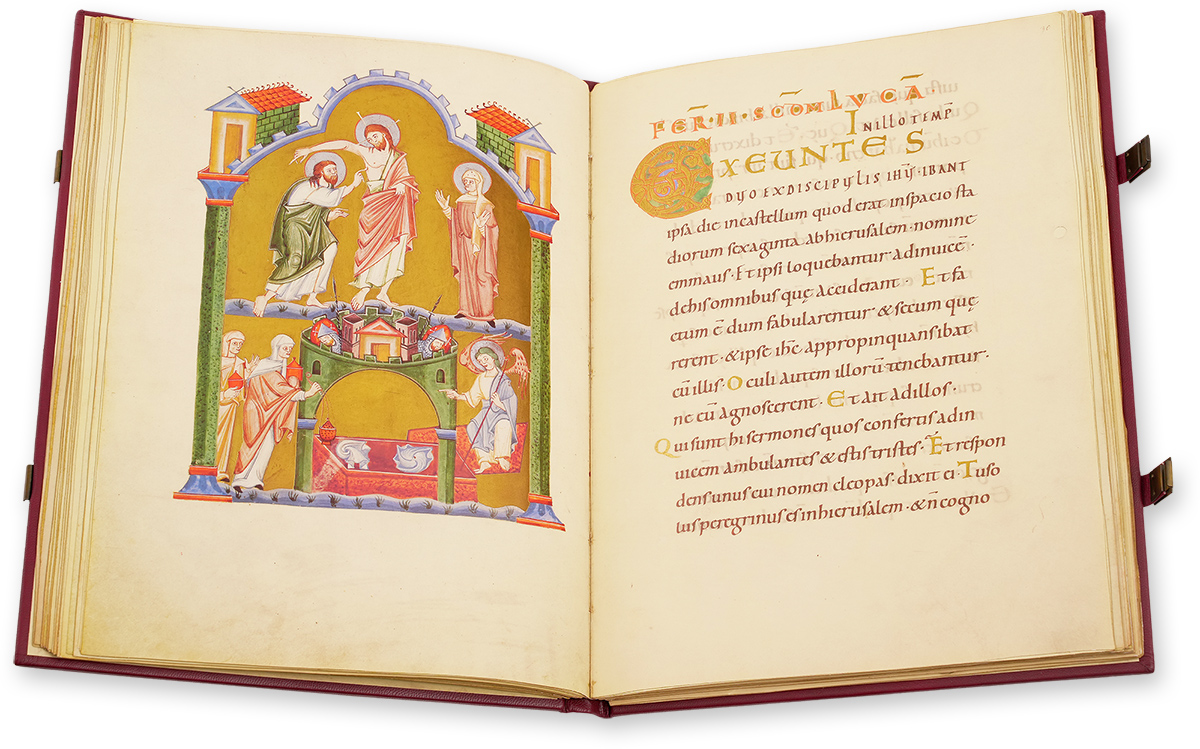

Pacino de Bonaguida's wonderful Trecento miniature, on the other hand, shows the scene in a hilly landscape against a deep blue background. The much more naturalistic marble sarcophagus stands outdoors, while the angel sits casually on the high rim of the open tomb. The removed lid is only hinted at in the background here.

Likewise, the miniature in the Brandenburg Evangeliary transposes the scene into a landscape. The open tomb stands on a lush green meadow strewn with flowers, which provides a strong earthly contrast to the golden background in the upper third of the picture. In the grass there are also three other figures that often complement the iconography of the tomb: the sleeping guards - more on this later.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

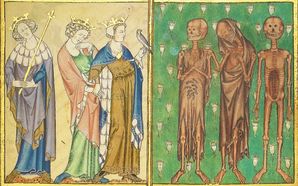

Two or Three Marys?

At this point it may be surprising that not even the representation of the women at the tomb is uniform. So there are just as many pictures with two Marys as with three. The fact that they also all bear the same name does not make the whole thing less confusing. However, this corresponds to the differing gospels, which do not tell the story in a uniform way either. Mark describes the situation most thoroughly:

"And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and [Mary] Salome, had bought sweet spices, that they might come and anoint him. And very early in the morning the first day of the week, they came unto the sepulchre at the rising of the sun. And they said among themselves, Who shall roll us away the stone from the door of the sepulchre? And when they looked, they saw that the stone was rolled away: for it was very great. And entering into the sepulchre, they saw a young man sitting on the right side, clothed in a long white garment; and they were affrighted. And he saith unto them, Be not affrighted: Ye seek Jesus of Nazareth, which was crucified: he is risen; he is not here: behold the place where they laid him. But go your way, tell his disciples and Peter that he goeth before you into Galilee: there shall ye see him, as he said unto you. And they went out quickly, and fled from the sepulchre; for they trembled and were amazed: neither said they any thing to any man; for they were afraid." (Mark 16, 1-8)

To the facsimile

Experience more

The Guards at the Tomb of Christ

In many miniatures, the basic pictorial staff is complemented by two to four tomb guards, who are not mentioned at all in the Gospels at the encounter of the women and the angel. Only Matthew mentions them a few passages earlier:

"Now the next day, that followed the day of the preparation, the chief priests and Pharisees came together unto Pilate, Saying, Sir, we remember that that deceiver said, while he was yet alive, After three days I will rise again. Command therefore that the sepulchre be made sure until the third day, lest his disciples come by night, and steal him away, and say unto the people, He is risen from the dead: so the last error shall be worse than the first. Pilate said unto them, Ye have a watch: go your way, make it as sure as ye can. So they went, and made the sepulchre sure, sealing the stone, and setting a watch." (Matt 27, 62-66)

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The guards have an enormously important role due to the fact that they were sent by Christ's opponents: their presence was interpreted as proof that the body had not been stolen, but that a miracle had taken place. This may be the reason for their widespread representation, long canonized in the late Middle Ages.

As in the Brandenburg Evangeliary, the guards are mostly asleep or at least distracted as in the case of the Sacramentary of Henry II. Here, moreover, it becomes apparent how difficult it was at first to integrate the figures into the scene: the two guards sit inconspicuously on the roof of the mausoleum and look boredly around, without noticing the women and the angel. The Salzburg Pericopes even show just the heads of the sleeping guards hidden above the burial chamber.

Experience more

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

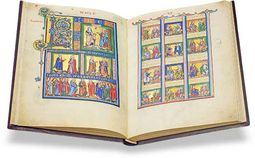

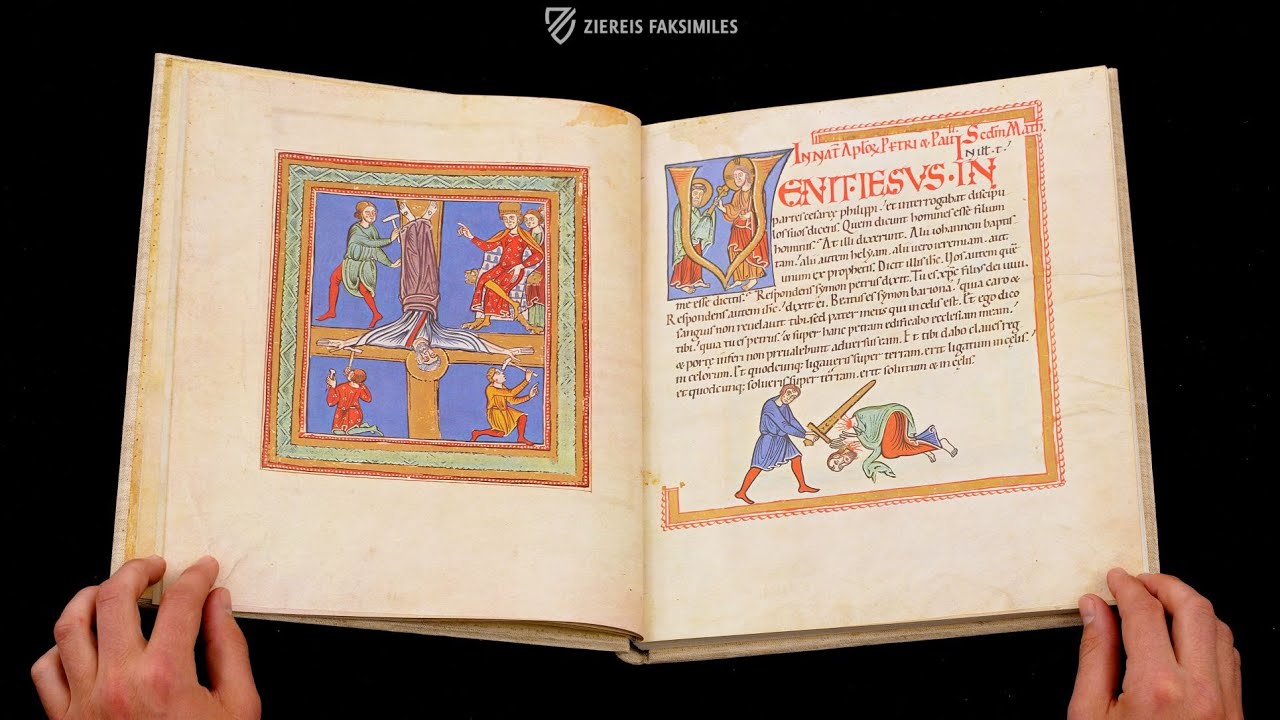

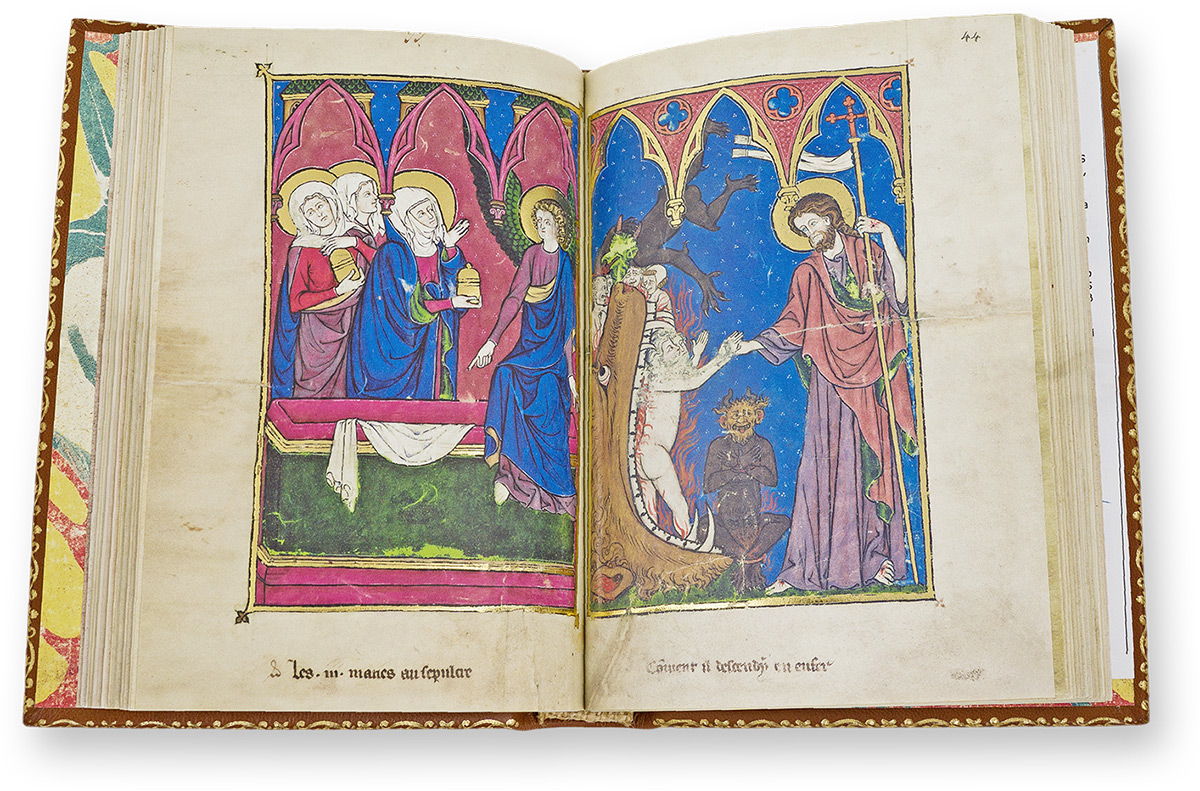

Other illuminators literally squeezed the figures right next to the scene. This is particularly clear in the New Testament: while the three Marys approach the tomb from the left, the guards sleep piled up on top of each other on the right side and do not even have any more ground under them. In the late Middle Ages, a solution is established that is probably perceived as more elegant, in which the guards are arranged in front of or below the sarcophagus - often arranged in a complete mess.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

The Shroud

To the facsimile

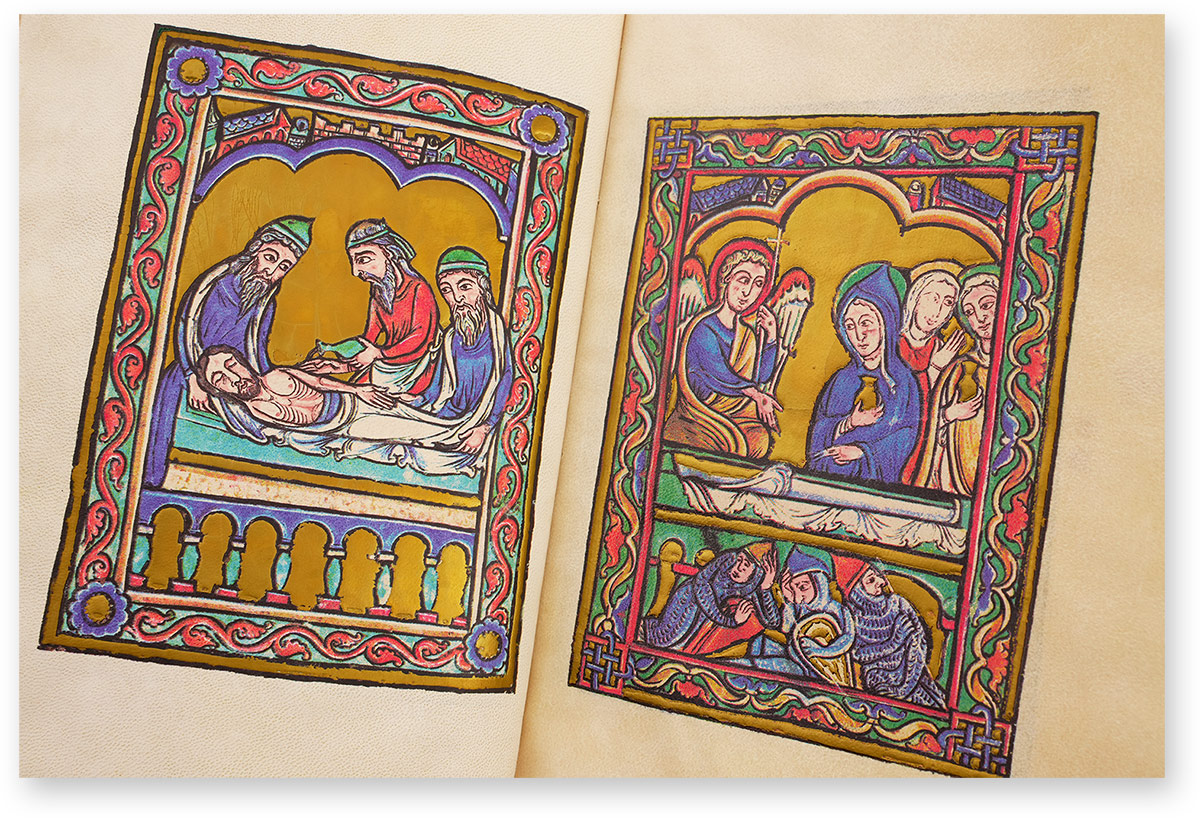

In many miniatures, the shroud of Christ plays an important role as a visualization of the mystery of the resurrection - as unimpressive as it may sometimes be. The usually white cloth is the only trace of the earthly Jesus and at the same time the proof that he was buried in the tomb. It mostly hovers artfully tied together in front of the dark emptiness of the sarcophagus or tomb, as for example in the Passau Evangeliary or in the Sacramentary of Henry II. In the Life of Christ, on the other hand, there is a quite realistic depiction that shows the cloth spread out on the empty deathbed as if Christ had just disappeared.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

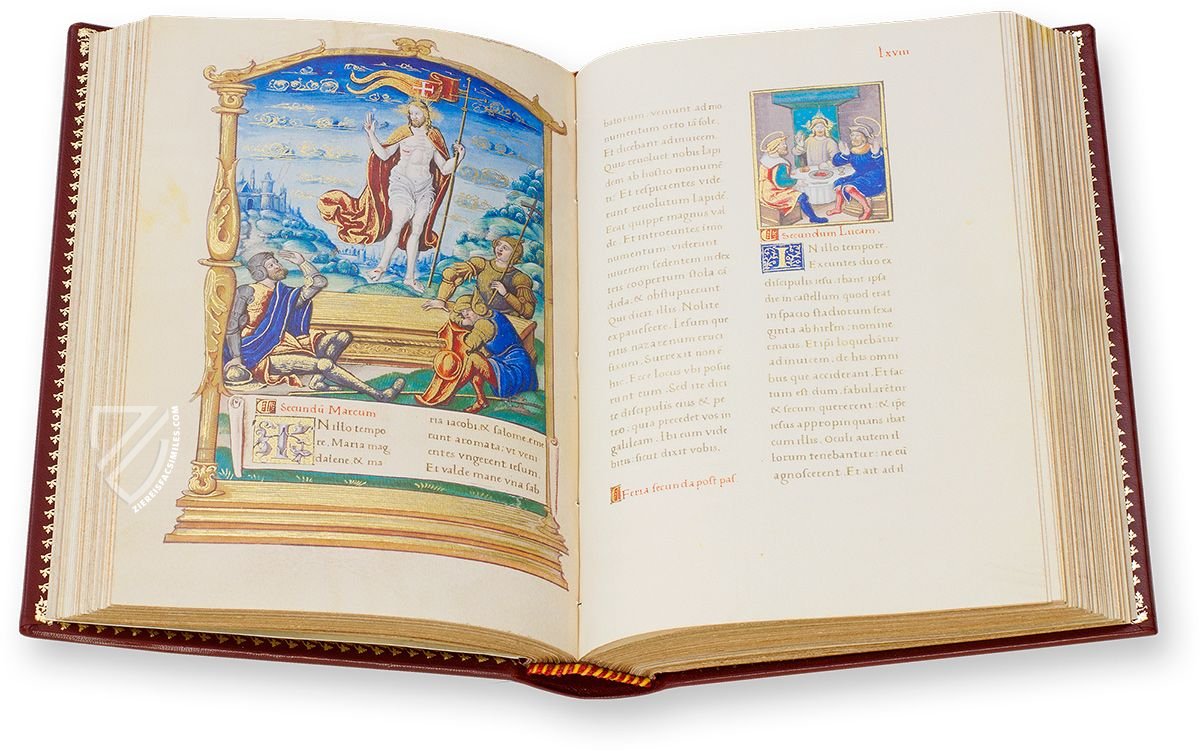

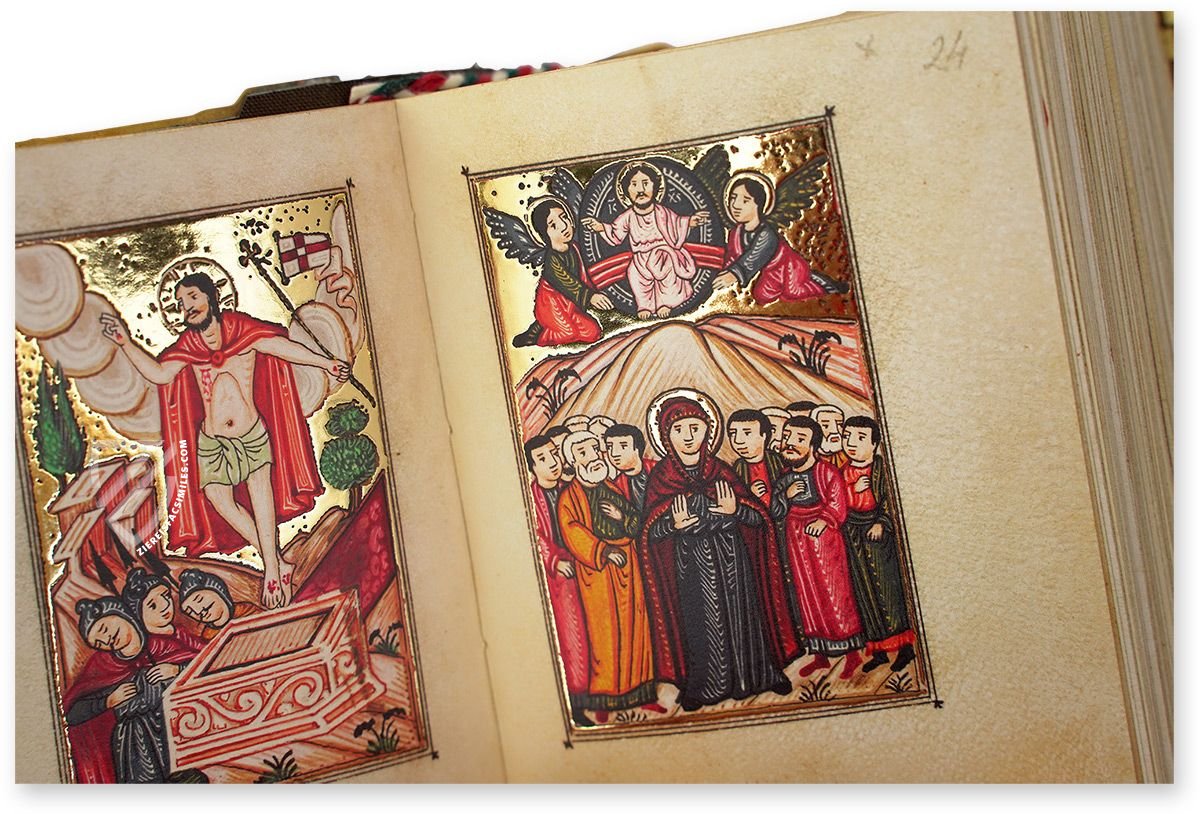

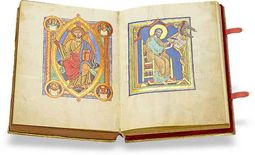

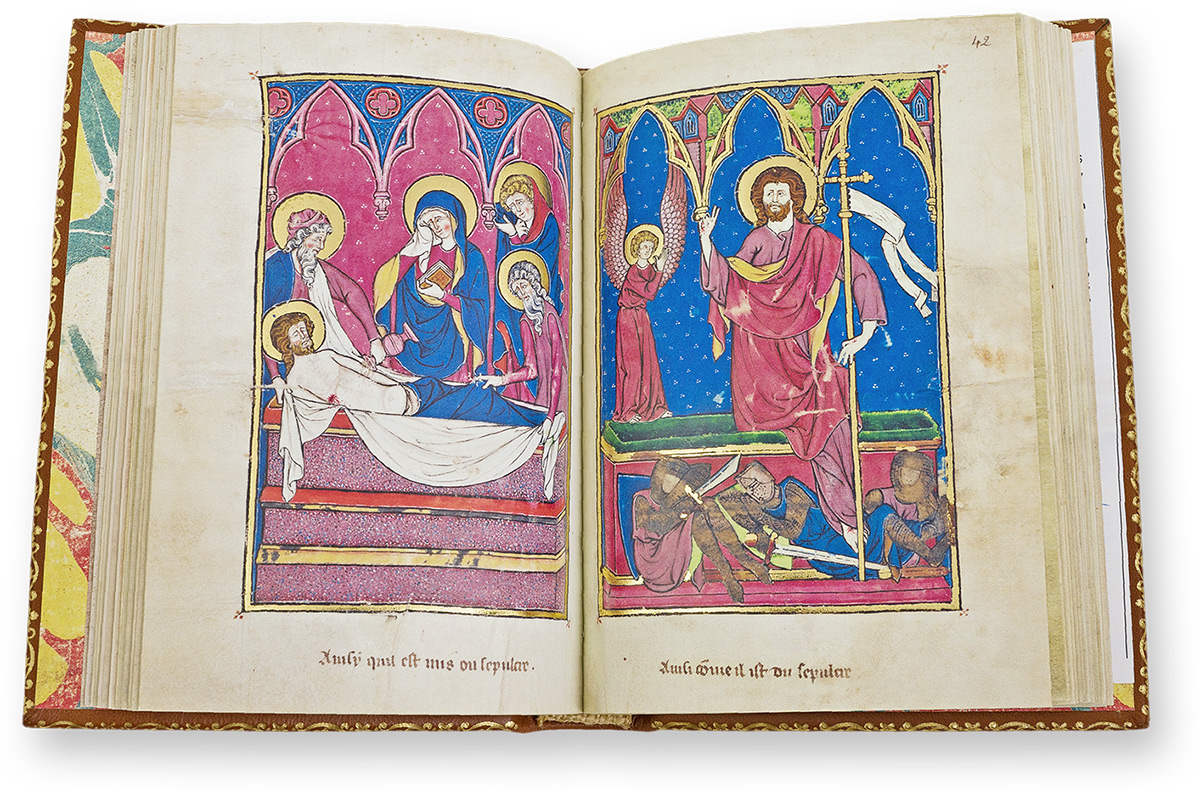

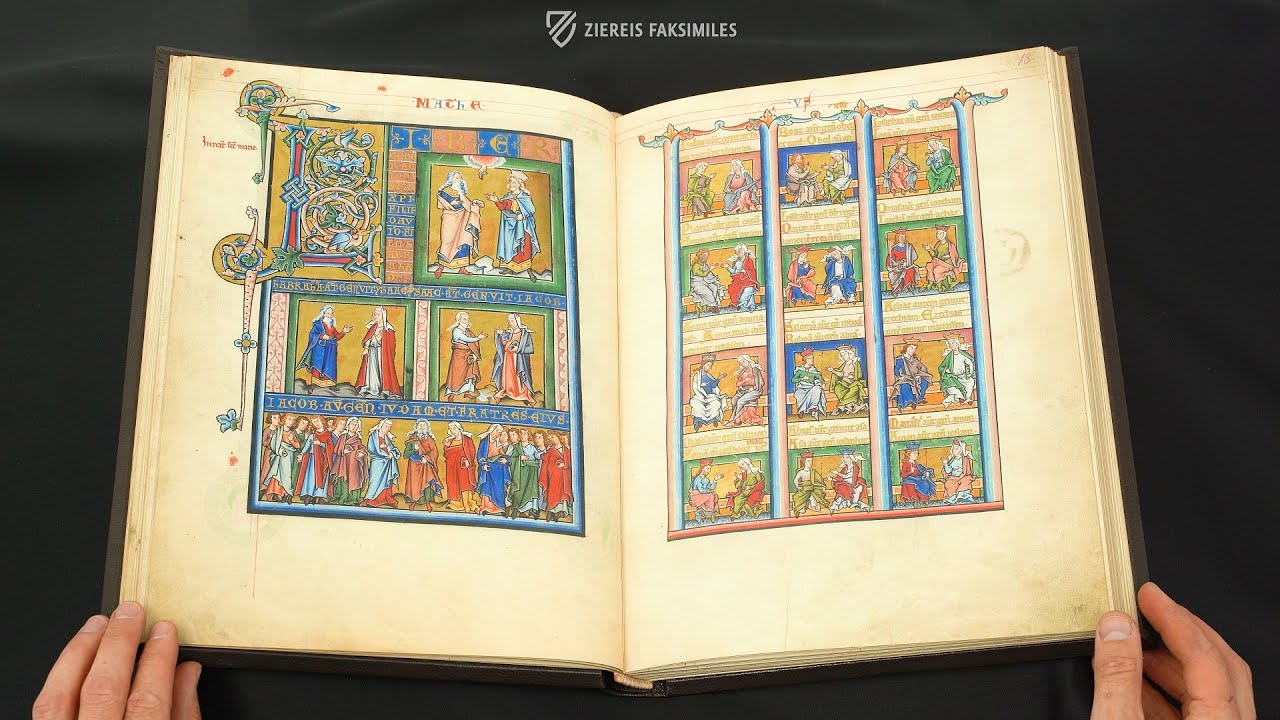

Resurrection from the Sarcophagus

In the late Middle Ages, the empty tomb increasingly fell into the background. Instead, people became increasingly interested in the Resurrection itself, and a new type of image emerged that was to find widespread use well into modern times, especially in panel painting: The Risen Christ ascends or floats from his tomb, which usually continues to retain the form of the sarcophagus, with a gesture of blessing and a triumphal cross. Christ's victory over death becomes the central pictorial theme.

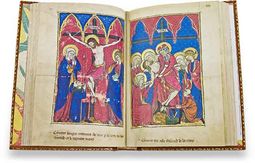

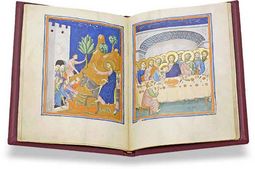

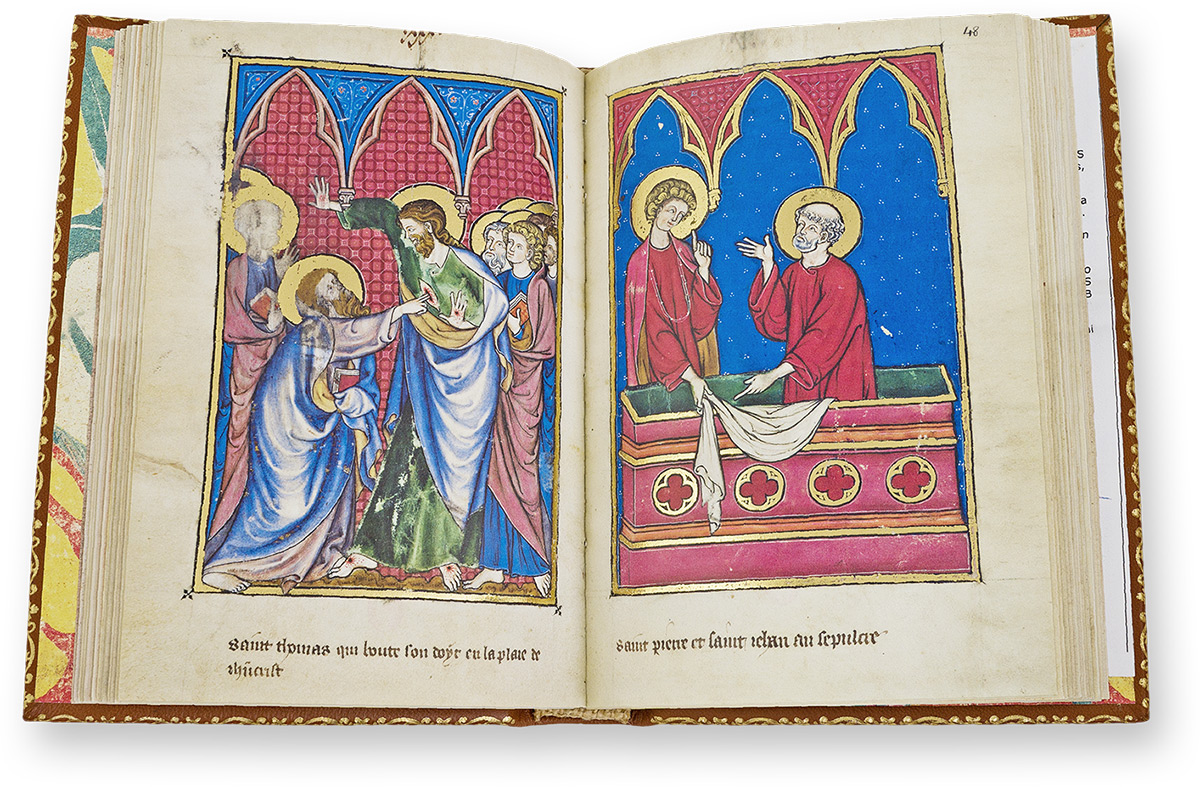

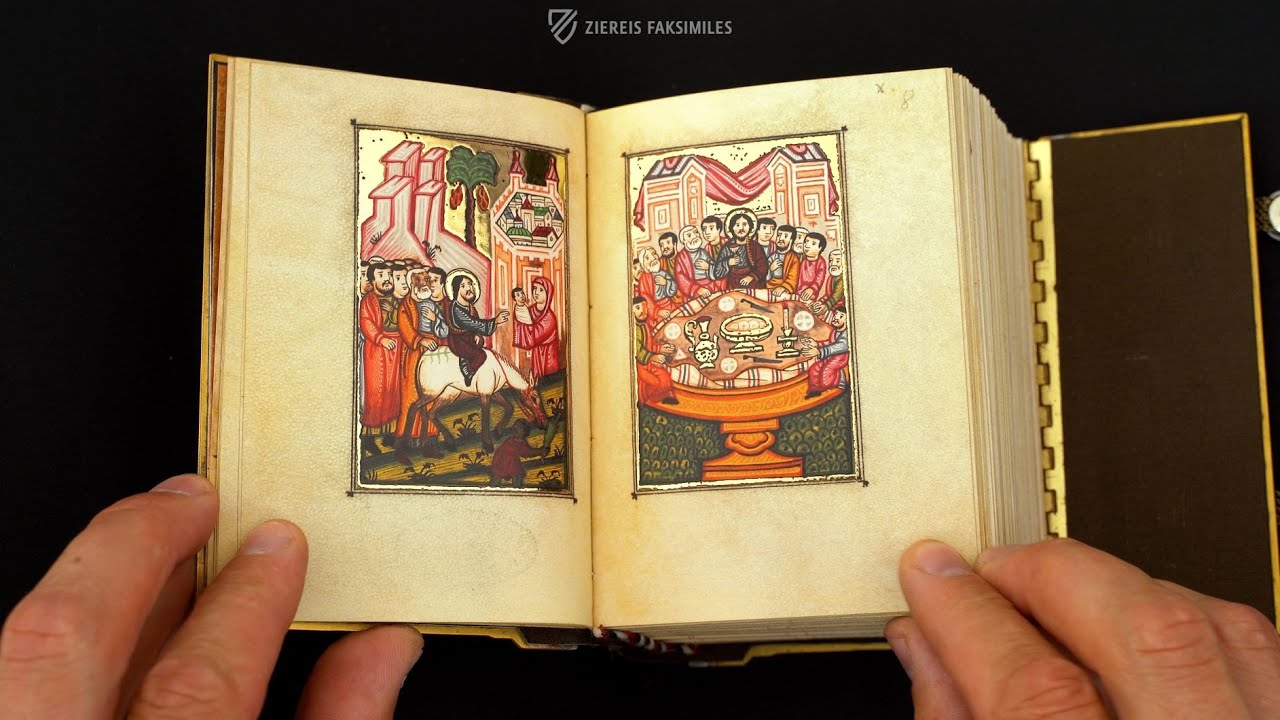

The Passion cycle of the Anglo-Norman Martyrology from the end of the 13th century holds a magnificent combination of the different types of images. Here, Christ's Entombment is followed by the Resurrection with the participation of an angel. Two folios later, the three Marys at the empty tomb are additionally shown communicating with another angel. Later, the empty tomb even appears a third time: in particular, the shroud is inspected by the two disciples John and Peter.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

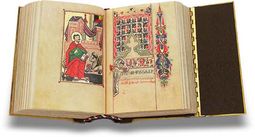

While the guards in the Resurrection miniature of the Anglo-Norman Martyrology are sleeping, the Mainz Gospels already indicate the further development of this group of figures: Full of terror, they look up at the Christ rising from the tomb and try to escape his glory in all directions. This variation became increasingly popular in the further course of the Middle Ages and modern times, as shown, for example, in the Gospel Book of Charles d'Orléans, Count of Angoulême. Here the left guard sitting on the ground seems to be almost blinded by Christ's triumph.

Experience more

To the facsimile

The symbolism of the grave and the Resurrection also appears in the liturgical instrument of the Eucharistic celebration during the medieval Mass - namely in the chalice, in which the transformation of the wine into the blood of Christ for communion still takes place today. The chalice was not only seen as a practical device for this process, but was assigned many other layers of meaning: It is, on the one hand, the mystical site of the said transformation, the transubstantiation, but also a reference to the so-called Lord's words that Jesus spoke to his disciples at the Last Supper, and thus also a direct reference to this same Last Supper, also called the Lord's Supper. Furthermore, the chalice was interpreted by medieval scholars as the tomb of Christ, since its purpose is to contain and veil the holy blood. According to this, looking into the chalice corresponds to looking into the tomb of Christ. In addition, there is the handling of the flat, circular host during the medieval liturgy. For some time, this was placed on the chalice and therefore interpreted as the equivalent of the stone with which the tomb of Christ was sealed.

This last example may illustrate how widely present the mystery of the empty tomb and the Resurrection were as central pillars of the Christian faith in the medieval world. It is not for nothing that Easter is the most important Christian holiday. The artistic, theological and liturgical exploration of the theme went hand in hand.

Experience more