The Warsaw Sforziad + La Bella Principessa

(3,000€ - 7,000€)

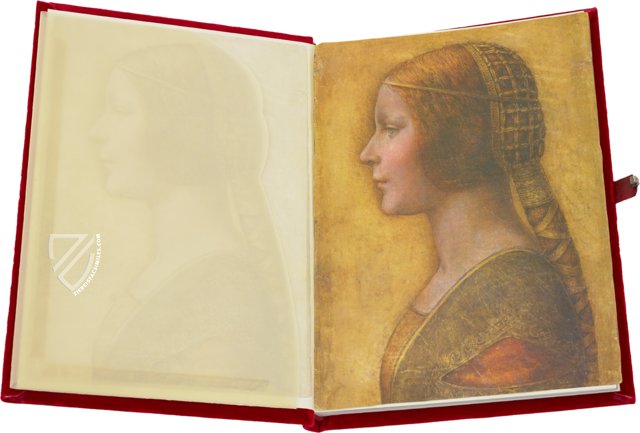

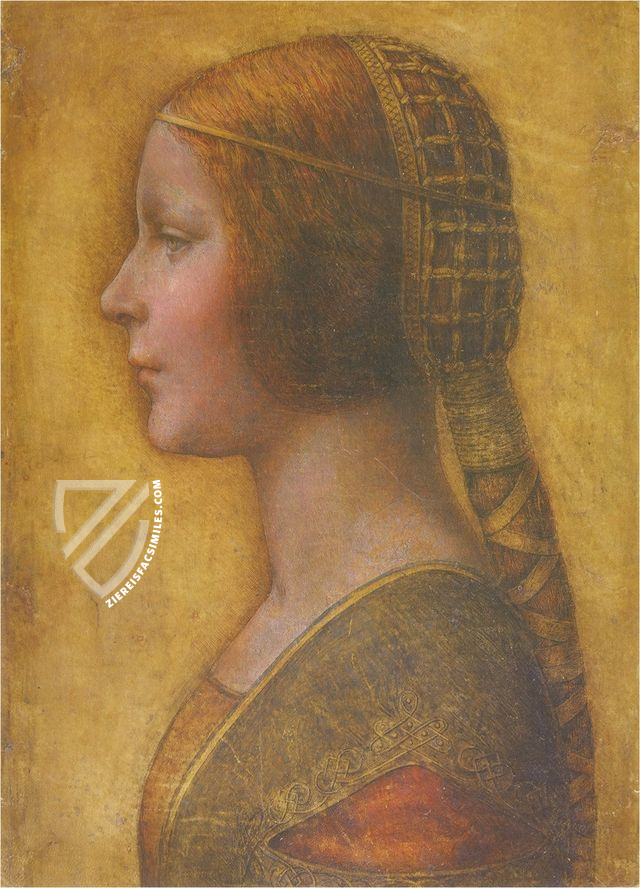

A rare and valuable Italian incunabulum in Poland and a mysterious, hotly-debated portrait auctioned in New York City in 1998 are connected through the Sforza family and the person of the great Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), the artist supposedly responsible for the work. The portrait of a young woman in profile was originally attributed to an anonymous 19th century German artist working in the Renaissance style. However, various stylistic indications point to a much older provenance, and carbon dating of the vellum on which it is pasted indicates that is has to predate the 19th century. A subsequent study of the work by Martin Kemp (b. 1942), a professor of art history at the University of Oxford and a leading expert on the art of Leonardo da Vinci, pointed to the famous polymath as possibly being responsible for the work. Furthermore, he connects it to a rare codex in Warsaw, one of only four surviving specimens of the 1490 Italian edition of the Sforziad, a propagandist poem of praise tracing the deeds of the Sforza. Although Kemp’s hypothesis is hotly debated among art historians, theses interconnected works represent spectacular specimens of late medieval art.

The Warsaw Sforziad + La Bella Principessa

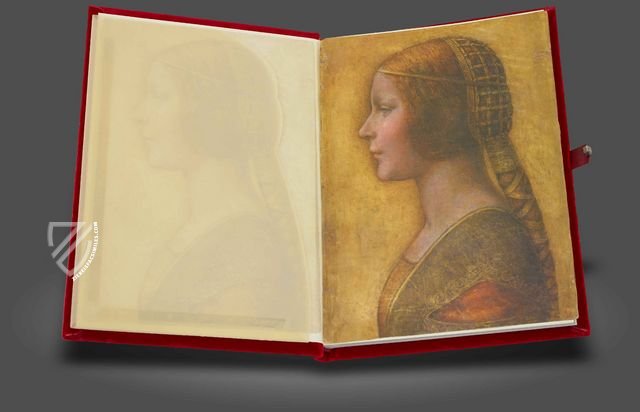

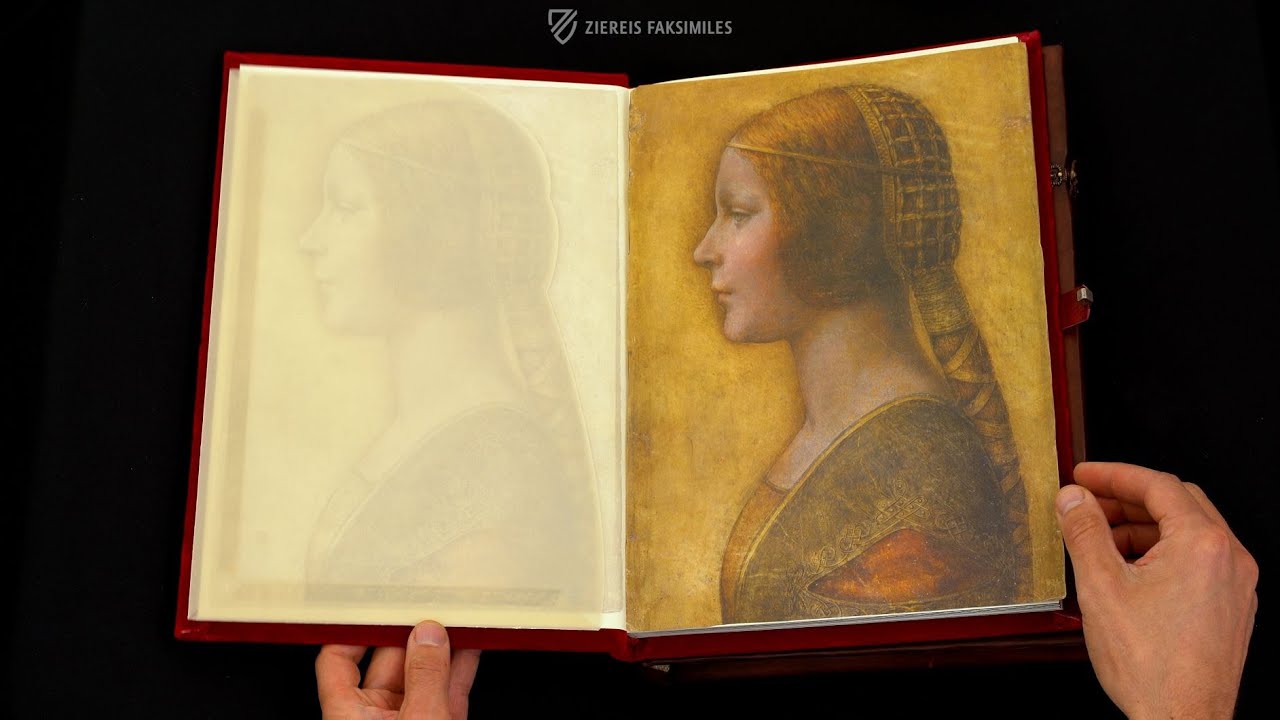

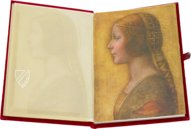

The idea of a newly discovered, previously unidentified painting by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) cannot help but fill one with a sense of the wonder and possibility of life, and more specifically, how many more splendid works of medieval art by great masters are just waiting to be discovered? The painting, measuring 33 x 23.9 cm, was originally identified as a 19th century work by an anonymous German artist, who created a Renaissance style portrait in profile. Since then, it has been identified as being an actual Renaissance portrait, not merely an homage, and furthermore, it has been postulated that it is the work of the great polymath Leonardo da Vinci. Additionally, the portrait may once have been in a copy of the Warsaw Sforziad, as evidenced by some artistic details, similar folio size, and the three holes in the vellum indicating it had once been part of a bound work. Although carbon dating of the vellum indicates that it cannot be from the 19th century and must be older, the Leonardo hypothesis is the source of concerted debate among art historians. Nonetheless, the last disclosed offer for the work was $80 million, which the owner has thus far chosen to decline. This work and the debate swirling around it attest to the fact that the study of medieval art is an ongoing and dynamic field, rather than being dusty and stagnant.

A Case of Mistaken Identity?

The portrait surfaced in 1998 at Christie’s Auction House in New York City and sold for ca. $22,000, a considerable sum for an anonymous work. Its owner, Kate Ganz, then sold the piece in 2007 to Peter Silverman, who suspected that the work was much older than was thought. The work became the focus of a 2010 study titled La Bella Principessa: The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinciby Martin Kemp (b. 1942), a professor of art history at the University of Oxford and a leading expert on the art of Leonardo da Vinci. He argued that the work was in fact a Leonardo and that the woman depicted in it was Bianca Sforza, who died in 1496 only months after being wed at the age of 13. It was this study that also first made the connection to the Warsaw Sforziad. These claims are, however, hotly debated, most notably in a 2011 New Yorker article, in which an artist by the name of John Biro revealed his successful attempts to reproduce the painting and have these fakes authenticated. Nonetheless, most scholars seem to accept that the work predates the 19th century, possibly originating from the 1490’s.

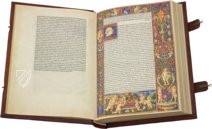

A Fabulous Incunabulum

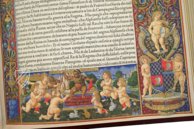

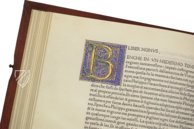

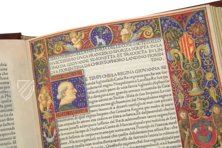

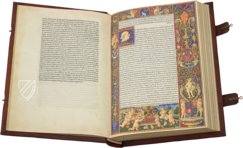

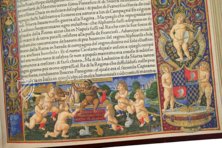

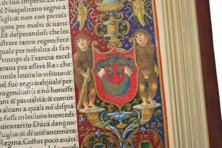

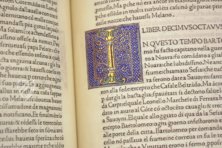

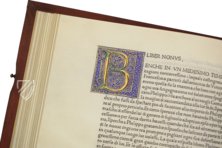

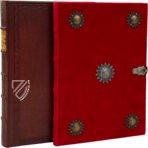

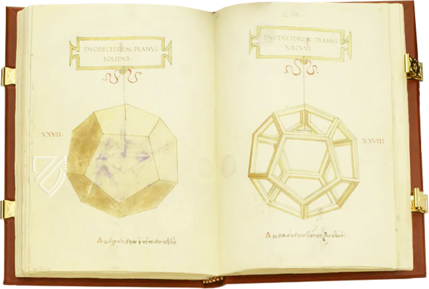

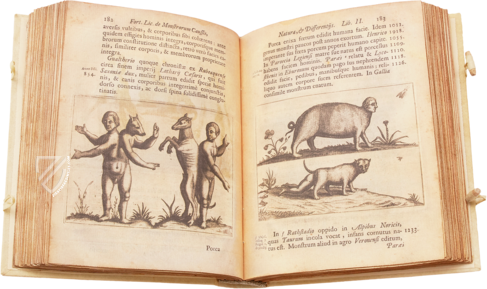

Kemp’s study also first made the connection between the Warsaw codex and the Sforziad. The Warsaw Sforziad is a poem of praise bordering on propaganda enumerating the deeds of the Sforza dynasty and takes the form of an incunabulum, an early printed book originating from before 1501. It is one of only four surviving specimens of the third edition of the work, printed in Milan ca. 1490. Unlike the previous two Latin editions, this is written in lingua florentina, i.e. the Tuscan dialect of Italian. Like many incunabula, these codices consist of printed texts that were then individually embellished with hand drawn initials, miniatures, and frames, as well as a frontispiece. Thus, the text by Giovanni Simonetta (1420–90), a politician and humanist, was laid down by the typographer Antonio Zarotto (1450–1510) and adorned by the miniaturist and engraver Giovanni Pietro Birago, who was active in late–16th century Milan. Originally commissioned by Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1444–76), later editions were commissioned by Ludovico Sforza (1452–1508), called “the Moor”, who was serving as regent for his young nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza (1469–94). This copy was gifted to Galeazzo Sanseverino (1458–1525), one of Ludovico’s military commanders and husband to Bianca. Therefore, it is likely that the codex was a wedding present, and thus contained the portrait of Bianca. It is believed that the codex later came to Poland with Bona Sforza (1494–1557), who married King Sigismund the Old (1467–1548) in 1518.

Codicology

- Alternative Titles

- La Sforziade di Varsavia

Das Warschauer Sforziad und die schöne Prinzessin

Rerum Gestarum Francisci Sfortiae Mediolanensium Ducis

Portrait of a Young Fiancée

Sforziada - Size / Format

- 408 pages + 1 painting / 33.0 - 33.4 × 23.1 - 23.6 cm

- Origin

- Italy

- Date

- Around 1490

- Epochs

- Style

- Illustrations

- A magnificently illuminated frontispiece and 35 ornamental decorative initials in gold

- Content

- Hymn of praise to Francsco Sforza to legitimize the succession of the Visconti by the Sforza and a portrait, probably showing Bianca Sforza, an illegitimate daughter of Ludovico Sforza, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci.

- Patron

- Ludovico Maria Sforza, il Moro (1452–1508), Duke of Milan

- Artist / School

- Leonardo da Vinci

Giovanni Simonetta

Giovanni Pietro Birago

Antonio Zarotto (typographer) - Previous Owners

- Bianca Sforza

Giangaleazzo Severino

The Warsaw Sforziad + La Bella Principessa

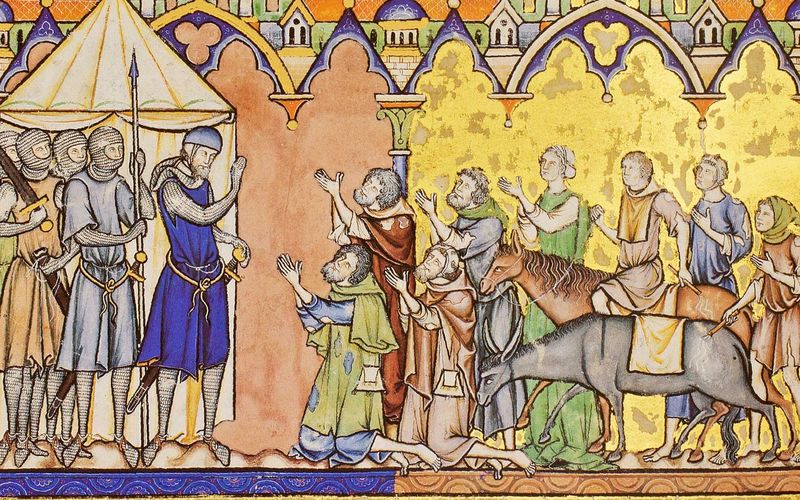

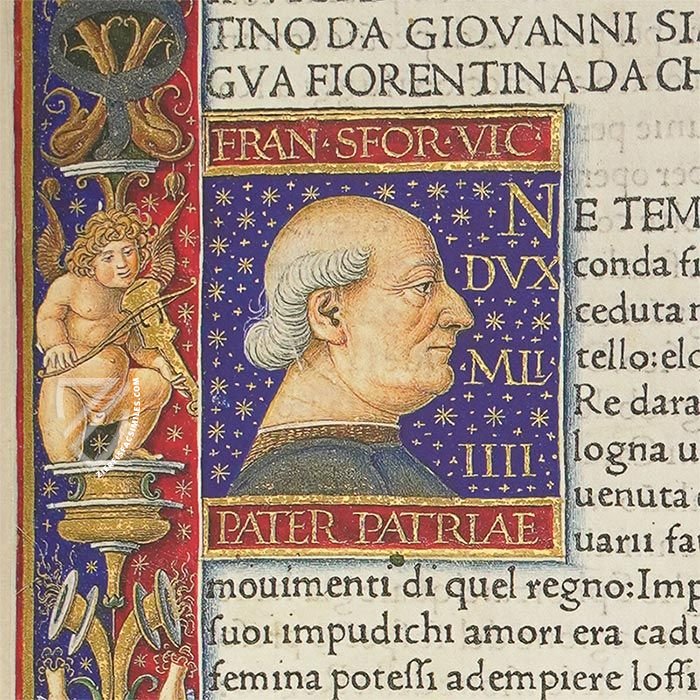

PATER PATRIAE

Identified here as the “father of his country”, Francesco I Sforza was the founder of the Sforza dynasty after he became Duke of Milan in 1450. Francesco started life as a condottiero or mercenary captain, rose to power thanks to his prowess as a general, and later distinguished himself as a masterful politician. This fine incunabulum was created to praise his achievements and shows him as elderly and looking back on a lifetime of achievements as a cherub celebrates him with music.

The Warsaw Sforziad + La Bella Principessa

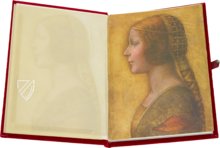

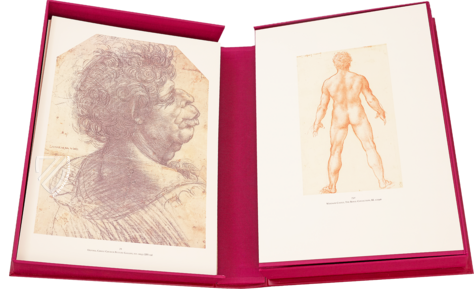

La Bella Principessa

One of the greatest artistic finds of the 20th century is also one of the most controversial: could this really be a previously undiscovered masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci? Its current owner, art dealer Peter Silverman certainly seems to think so, and after having acquired it for $22,000 he has declined offers as great as $80 million for it.

The painting reemerged in 1955 and was sold at auction in 1998 as a 19th century German recreation of a Renaissance portrait. Those arguing for its attribution to da Vinci insist that it is a portrait of Bianca Sforza, daughter of Duke Ludovico Sforza who died shortly after she was married at 14, and believe it was originally part of the codex at hand before being cut from it at a later date.

#1 La Sforziade di Varsavia

Languages: English, Italian, Polish

(3,000€ - 7,000€)

- Treatises / Secular Books

- Apocalypses / Beatus

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Bestiaries

- Bibles / Gospels

- Chronicles / History / Law

- Geography / Maps

- Saints' Lives

- Islam / Oriental

- Judaism / Hebrew

- Single Leaf Collections

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Literature / Poetry

- Liturgical Manuscripts

- Medicine / Botany / Alchemy

- Music

- Mythology / Prophecies

- Psalters

- Other Religious Books

- Games / Hunting

- Private Devotion Books

- Other Genres

- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Austria

- Belgium

- Belize

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Ethiopia

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hungary

- India

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Lebanon

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Netherlands

- Palestine

- Panama

- Peru

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- Serbia

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uzbekistan

- Vatican City

- A. Oosthoek, van Holkema & Warendorf

- Aboca Museum

- Ajuntament de Valencia

- Akademie Verlag

- Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA)

- Aldo Ausilio Editore - Bottega d’Erasmo

- Alecto Historical Editions

- Alkuin Verlag

- Almqvist & Wiksell

- Amilcare Pizzi

- Andreas & Andreas Verlagsbuchhandlung

- Archa 90

- Archiv Verlag

- Archivi Edizioni

- Arnold Verlag

- ARS

- Ars Magna

- Art Market

- ArtCodex

- AyN Ediciones

- Azimuth Editions

- Badenia Verlag

- Bärenreiter-Verlag

- Belser Verlag

- Belser Verlag / WK Wertkontor

- Benziger Verlag

- Bernardinum Wydawnictwo

- BiblioGemma

- Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vaticanstadt, Vaticanstadt)

- Bibliotheca Palatina Faksimile Verlag

- Bibliotheca Rara

- Boydell & Brewer

- Bramante Edizioni

- Bredius Genootschap

- Brepols Publishers

- British Library

- C. Weckesser

- Caixa Catalunya

- Canesi

- CAPSA, Ars Scriptoria

- Caratzas Brothers, Publishers

- Carus Verlag

- Casamassima Libri

- Centrum Cartographie Verlag GmbH

- Chavane Verlag

- Christian Brandstätter Verlag

- Circulo Cientifico

- Club Bibliófilo Versol

- Club du Livre

- CM Editores

- Collegium Graphicum

- Collezione Apocrifa Da Vinci

- Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses

- Coron Verlag

- Corvina

- CTHS

- D. S. Brewer

- Damon

- De Agostini/UTET

- De Nederlandsche Boekhandel

- De Schutter

- Deuschle & Stemmle

- Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft

- DIAMM

- Dropmore Press

- Droz

- E. Schreiber Graphische Kunstanstalten

- Ediciones Boreal

- Ediciones Grial

- Ediclube

- Edições Inapa

- Edilan

- Editalia

- Edition Deuschle

- Edition Georg Popp

- Edition Leipzig

- Edition Libri Illustri

- Editiones Reales Sitios S. L.

- Éditions de l'Oiseau Lyre

- Editions Medicina Rara

- Editorial Casariego

- Editorial Mintzoa

- Editrice Antenore

- Editrice Velar

- Edizioni Edison

- Egeria, S.L.

- Eikon Editores

- Electa

- Emery Walker Limited

- Enciclopèdia Catalana

- Eos-Verlag

- Ephesus Publishing

- Ernst Battenberg

- Eugrammia Press

- Extraordinary Editions

- Fackelverlag

- Facsimila Art & Edition

- Facsimile Editions Ltd.

- Facsimilia Art & Edition Ebert KG

- Faksimile Verlag

- Feuermann Verlag

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- Franco Cosimo Panini Editore

- Friedrich Wittig Verlag

- Fundación Hullera Vasco-Leonesa

- G. Braziller

- Gabriele Mazzotta Editore

- Gebr. Mann Verlag

- Gesellschaft für graphische Industrie

- Getty Research Institute

- Giovanni Domenico de Rossi

- Giunti Editore

- Graffiti

- Grafica European Center of Fine Arts

- Guido Pressler

- Guillermo Blazquez

- Gustav Kiepenheuer

- H. N. Abrams

- Harrassowitz

- Harvard University Press

- Helikon

- Hendrickson Publishers

- Henning Oppermann

- Herder Verlag

- Hes & De Graaf Publishers

- Hoepli

- Holbein-Verlag

- Houghton Library

- Hugo Schmidt Verlag

- Idion Verlag

- Il Bulino, edizioni d'arte

- ILte

- Imago

- Insel Verlag

- Insel-Verlag Anton Kippenberger

- Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses

- Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

- Introligatornia Budnik Jerzy

- Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana - Treccani

- Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini

- Istituto Geografico De Agostini

- Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato

- Italarte Art Establishments

- Jan Thorbecke Verlag

- Johnson Reprint Corporation

- Johnson Reprint Corporation

- Josef Stocker

- Josef Stocker-Schmid

- Jugoslavija

- Karl W. Hiersemann

- Kasper Straube

- Kaydeda Ediciones

- Kindler Verlag / Coron Verlag

- Kodansha International Ltd.

- Konrad Kölbl Verlag

- Kurt Wolff Verlag

- La Liberia dello Stato

- La Linea Editrice

- La Meta Editore

- Lambert Schneider

- Landeskreditbank Baden-Württemberg

- Leo S. Olschki

- Les Incunables

- Liber Artis

- Library of Congress

- Libreria Musicale Italiana

- Lichtdruck

- Lito Immagine Editore

- Lumen Artis

- Lund Humphries

- M. Moleiro Editor

- Maison des Sciences de l'homme et de la société de Poitiers

- Manuscriptum

- Martinus Nijhoff

- Maruzen-Yushodo Co. Ltd.

- MASA

- Massada Publishers

- McGraw-Hill

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Militos

- Millennium Liber

- Müller & Schindler

- Nahar - Stavit

- Nahar and Steimatzky

- National Library of Wales

- Neri Pozza

- Nova Charta

- Oceanum Verlag

- Odeon

- Omnia Arte

- Orbis Mediaevalis

- Orbis Pictus

- Österreichische Staatsdruckerei

- Oxford University Press

- Pageant Books

- Parzellers Buchverlag

- Patrimonio Ediciones

- Pattloch Verlag

- PIAF

- Pieper Verlag

- Plon-Nourrit et cie

- Poligrafiche Bolis

- Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg

- Prestel Verlag

- Princeton University Press

- Prisma Verlag

- Priuli & Verlucca, editori

- Pro Sport Verlag

- Propyläen Verlag

- Pytheas Books

- Quaternio Verlag Luzern

- Reales Sitios

- Recht-Verlag

- Reichert Verlag

- Reichsdruckerei

- Reprint Verlag

- Riehn & Reusch

- Roberto Vattori Editore

- Rosenkilde and Bagger

- Roxburghe Club

- Salerno Editrice

- Saltellus Press

- Sandoz

- Sarajevo Svjetlost

- Schöck ArtPrint Kft.

- Schulsinger Brothers

- Scolar Press

- Scrinium

- Scripta Maneant

- Scriptorium

- Shazar

- Siloé, arte y bibliofilia

- SISMEL - Edizioni del Galluzzo

- Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología

- Société des Bibliophiles & Iconophiles de Belgique

- Soncin Publishing

- Sorli Ediciones

- Stainer and Bell

- Studer

- Styria Verlag

- Sumptibus Pragopress

- Szegedi Tudomànyegyetem

- Taberna Libraria

- Tarshish Books

- Taschen

- Tempus Libri

- Testimonio Compañía Editorial

- TGB Limited Editions

- Thames and Hudson

- The Clear Vue Publishing Partnership Limited

- The Facsimile Codex

- The Folio Society

- The Marquess of Normanby

- The Richard III and Yorkist History Trust

- Tip.Le.Co

- TouchArt

- TREC Publishing House

- TRI Publishing Co.

- Trident Editore

- Tuliba Collection

- Typis Regiae Officinae Polygraphicae

- Union Verlag Berlin

- Universidad de Granada

- Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden

- University of California Press

- University of Chicago Press

- Urs Graf

- Vallecchi

- Van Wijnen

- VCH, Acta Humaniora

- VDI Verlag

- VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik

- Verlag Anton Pustet / Andreas Verlag

- Verlag Bibliophile Drucke Josef Stocker

- Verlag der Münchner Drucke

- Verlag für Regionalgeschichte

- Verlag Styria

- Vicent Garcia Editores

- W. Turnowski Ltd.

- W. Turnowsky

- Waanders Printers

- Wiener Mechitharisten-Congregation (Wien, Österreich)

- Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft

- Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft

- Wydawnictwo Dolnoslaskie

- Xuntanza Editorial

- Zakład Narodowy

- Zollikofer AG