Letters of Alcuin and Other Documents

(under 1,000€)

Arno (ca. 740–821) led an eventful life in eventful times: a native of Isengau in Bavaria, he was an abbot in Flanders before becoming Bishop of Salzburg in 785. He became a friend and confidant of Charlemagne (748–814) and his his closest advisor, the great scholar Alcuin (c. 735–804). How close a bond he was able to forge with these historical figures is shown by Arno's presence at Charlemagne's imperial coronation in Rome in 800 and, even before that, by his journey there in 797 on Charlemagne's behalf: there he was able to obtain the elevation of Salzburg to an archbishopric and was tasked with missionizing Carinthia and Pannonia. Alcuin subsequently advised him not to impose the usual tithe on the new territories, whereupon Arno introduced the so-called Slavic tithe, which demanded fewer dues. Thus, the collection of letters and writings of Alcuin, probably compiled by Arno, gives an extraordinary insight into the heart of the Frankish Empire.

Letters of Alcuin and Other Documents

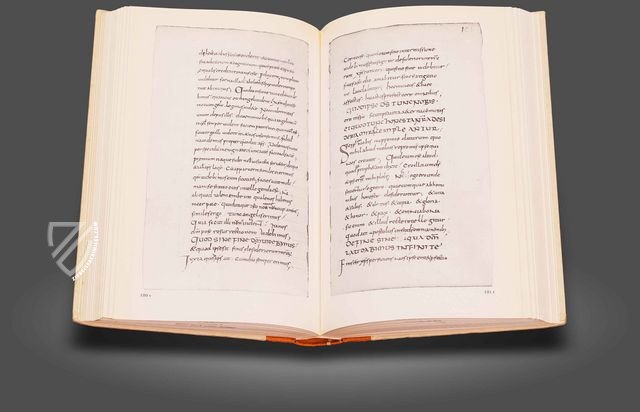

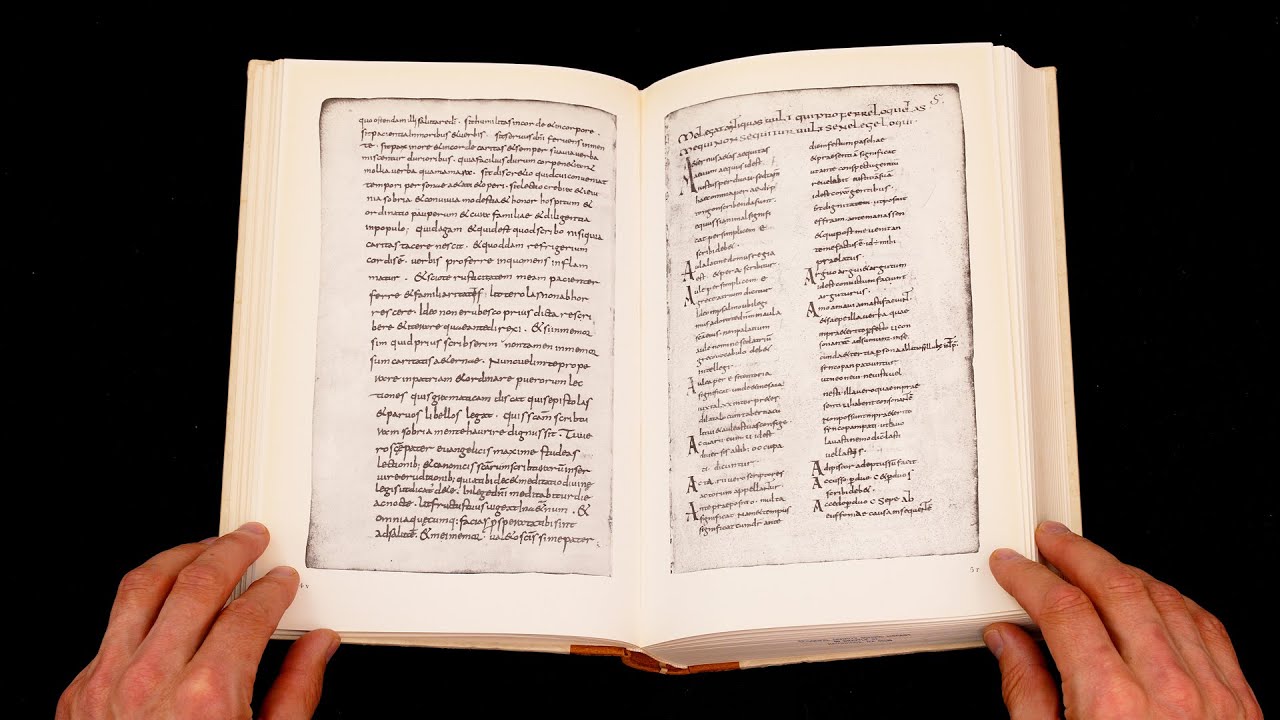

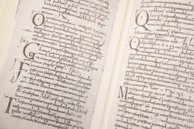

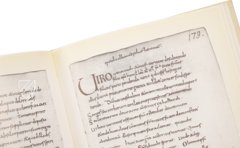

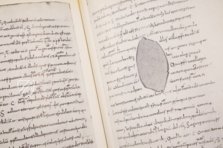

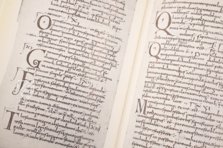

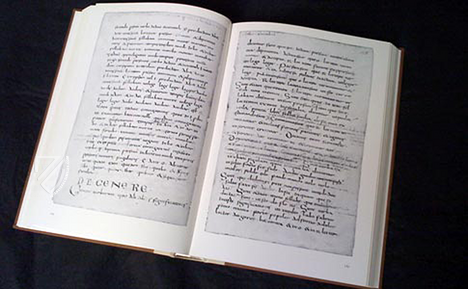

Described by Einhard (ca. 775–840) as “the most learned man anywhere to be found”, Alcuin (ca. 735–804) was arguably the most important scholar of the Carolingian Renaissance. The individual parts of this codex consist of his correspondence with Archbishop Arno (ca. 740–821), who was travelling from Rome to Francia where he would meet with Alcuin and Charlemagne (748–814) during the year 798; the last letter was written at the end of January 799. The manuscript is a compilation in the truest sense of the word and is of the greatest value for historians, theologians, and philologists. Other texts in the manuscript include two Gothic alphabets, Anglo-Saxon runes, and more. There is evidence of the hands of numerous scribes who often took turns in mid-sentence. This compilation is the most important source for details of Alcuin’s life and is thus represents a precious, irreplaceable historical record.

A True Compilation

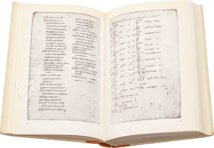

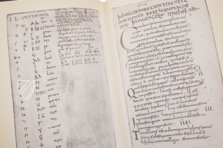

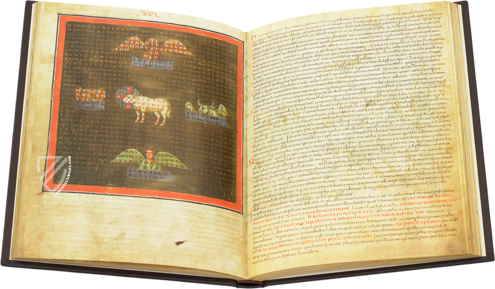

The content of the codex is not very coherent, which indicates that they were selected according to the personal interests of Archbishop Arno. Although a date of origin during the 9th or even the 10th century has also been theorized, the manuscript was probably created in the scriptorium of the Saint-Amand Monastery in French Flanders ca. 799. Aside from containing the voluminous correspondence between Alcuin and Arno, it also includes: Alcuin’s commentary on the Epistle to the Romans; an orthographic treatise; a Greek alphabet and Syllabogram; a chart of the Roman numerals; Anglo-Saxon runes also known as the “futhorc”; an excerpt from Genesis in the Gothic Bible; a cryptogram; two Gothic alphabets – one in the original arrangement and one partly arranged like a Latin alphabet with the names of the letters and translations into Latin and Old High German as well as notes on the proper pronunciation and spelling in the Gothic language.

Plans for Rebuilding Rome

Two texts not written by Alcuin concerning the topography of the city of Rome are also included in the codex: Notitia ecclesiarium urbis Romae or “Notice of the Church of the City of Rome” and De locis sanctis martyrum quae sunt foris civitatis Romae or “The Locks of the Holy Martyrs Outside the City of Rome”. They appear to be particularly focused on its shrines and are accompanied by correspondence between Arno and Alcuin about the possibility of rebuilding of a monastery. As such, this manuscript also represents a desire during the Early Middle Ages to restore Rome to its former glory and position of political authority. In fact, Emperor Otto III moved his capital to Rome at the end of the 10th century, revived the elaborate customs and ceremonies of the ancient Romans as well as the city’s administration, and even took to wearing purple dyed togas.

Alcuin and the Carolingian Renaissance

Born in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, Alcuin of York already had an established reputation for brilliance when he was invited by Charlemagne to be the master scholar and teacher at the Frankish court in Aachen in 782. He spent the next eight years personally instructing Charlemagne and his sons while also establishing a reputation as the foremost mind and chief architect of the Carolingian Renaissance. Many of the most important intellectuals of the period were his pupils. One of his greatest achievements was the perfection of Carolingian minuscule, which he established as a standardized, easily legible script across Western and Central Europe. Alcuin was also the author of numerous theological, dogmatic, philosophical, mathematical, logical, and grammatical treatises as well as numerous poems.

Semi-Retirement in Tours

Alcuin grew weary of his court duties as he entered his 60s and was appointed Abbot of Marmoutier Abbey near Tours, France by Charlemagne in 796 on the condition that he should make himself available to the King if needed. There he spent the rest of his life largely overseeing the implementation of Carolingian minuscule in the abbey’s scriptorium before he died on May 19th, 804 and was buried in the Basilica of St. Martin, Tours. His epitaph reads:

Dust, worms, and ashes now ...

Alcuin my name, wisdom I always loved,

Pray, reader, for my soul.

Codicology

- Alternative Titles

- Die Alkuin-Briefe und andere Traktate

Salzburg-Wiener Alcuin-Handschrift

Salzburg-Wiener Handschrift - Size / Format

- 410 pages / 28.8 × 14.0 cm

- Origin

- France

- Date

- End of the 8th century, later additions from the 9th and 10th centuries

- Epochs

- Style

- Language

- Illustrations

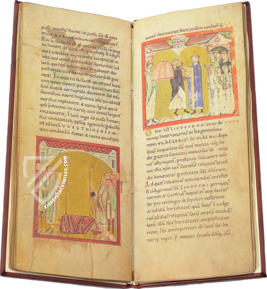

- Initials and display script

- Content

- Letters and treatises by Alcuin, the Greek alphabet “formae litterarum secundum Graecos”, Greek syllabary, Roman numerals, the Old English runic alphabet Futhark, key for the bonifatic notes, cryptogram, two Gothic alphabets

- Patron

- Archbishop Arn of Salzburg (after 740–821)

- Artist / School

- Alcuin (ca. 735–804) (author)

Archbishop Arn of Salzburg (after 740–821) (compiler?) - Previous Owners

- Perhthar

Frederick of Chiemgau, Archbishop of Salzburg

Domkapitelbibliothek Salzburg

Letters of Alcuin and Other Documents

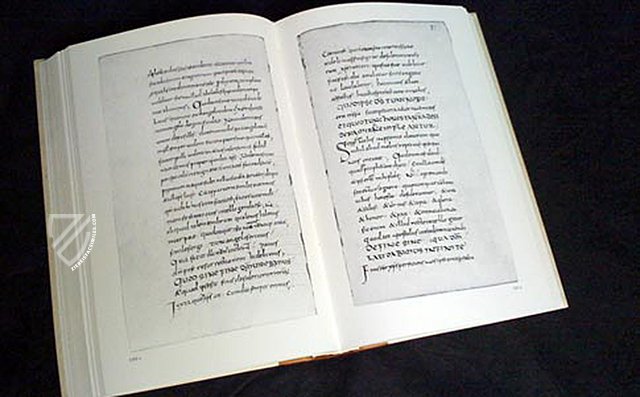

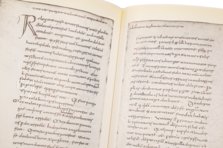

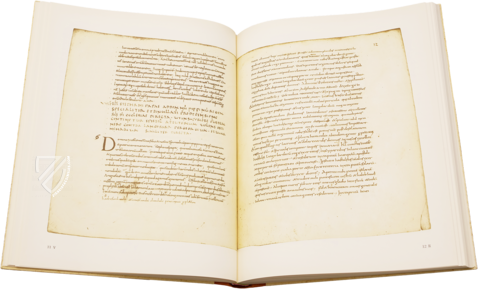

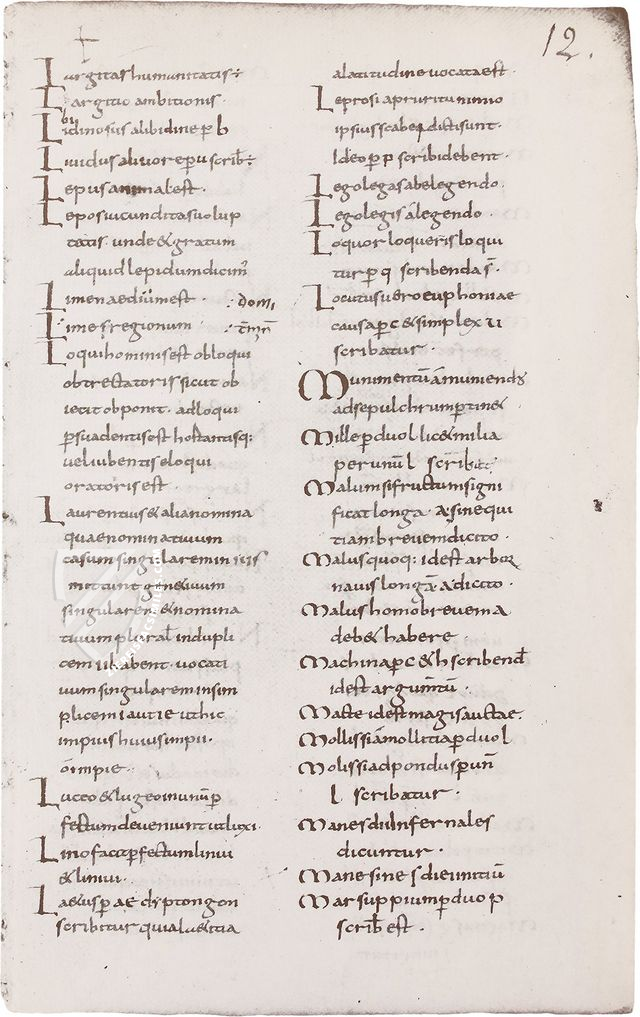

Alkuin – De Orthographia

Alcuin's treatise on orthography is emblematic of the educational ambitions of Charlemagne and his closest advisor: a standardized, 'correct' Latin, together with the Carolingian minuscule, was to become the language of scholarship and facilitate supra-regional communication.

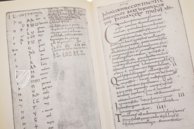

In two columns, fol. 12r lists Latin headwords beginning with L and M. The break in the middle of the right-hand column is indicated by a slight enlargement of the M initial, which introduces the first word beginning with M: “Munimentum” - meaning fortification, protection.

#1 Die Alkuin-Briefe und andere Traktate

Language: German

(under 1,000€)

- Treatises / Secular Books

- Apocalypses / Beatus

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Bestiaries

- Bibles / Gospels

- Chronicles / History / Law

- Geography / Maps

- Saints' Lives

- Islam / Oriental

- Judaism / Hebrew

- Single Leaf Collections

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Literature / Poetry

- Liturgical Manuscripts

- Medicine / Botany / Alchemy

- Music

- Mythology / Prophecies

- Psalters

- Other Religious Books

- Games / Hunting

- Private Devotion Books

- Other Genres

- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Austria

- Belgium

- Belize

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Ethiopia

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hungary

- India

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Lebanon

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Netherlands

- Palestine

- Panama

- Peru

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- Serbia

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uzbekistan

- Vatican City

- A. Oosthoek, van Holkema & Warendorf

- Aboca Museum

- Ajuntament de Valencia

- Akademie Verlag

- Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA)

- Aldo Ausilio Editore - Bottega d’Erasmo

- Alecto Historical Editions

- Alkuin Verlag

- Almqvist & Wiksell

- Amilcare Pizzi

- Andreas & Andreas Verlagsbuchhandlung

- Archa 90

- Archiv Verlag

- Archivi Edizioni

- Arnold Verlag

- ARS

- Ars Magna

- Ars Millenii

- Art Market

- ArtCodex

- AyN Ediciones

- Azimuth Editions

- Badenia Verlag

- Bärenreiter-Verlag

- Belser Verlag

- Belser Verlag / WK Wertkontor

- Benziger Verlag

- Bernardinum Wydawnictwo

- BiblioGemma

- Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vaticanstadt, Vaticanstadt)

- Bibliotheca Palatina Faksimile Verlag

- Bibliotheca Rara

- Boydell & Brewer

- Bramante Edizioni

- Bredius Genootschap

- Brepols Publishers

- British Library

- C. Weckesser

- Caixa Catalunya

- Canesi

- CAPSA, Ars Scriptoria

- Caratzas Brothers, Publishers

- Carus Verlag

- Casamassima Libri

- Centrum Cartographie Verlag GmbH

- Chavane Verlag

- Christian Brandstätter Verlag

- Circulo Cientifico

- Club Bibliófilo Versol

- Club du Livre

- Club Internacional del Libro

- CM Editores

- Collegium Graphicum

- Collezione Apocrifa Da Vinci

- Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses

- Coron Verlag

- Corvina

- CTHS

- D. S. Brewer

- Damon

- De Agostini/UTET

- De Nederlandsche Boekhandel

- De Schutter

- Deuschle & Stemmle

- Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft

- DIAMM

- Dropmore Press

- Droz

- E. Schreiber Graphische Kunstanstalten

- Ediciones Boreal

- Ediciones Grial

- Ediclube

- Edições Inapa

- Edilan

- Editalia

- Edition Deuschle

- Edition Georg Popp

- Edition Leipzig

- Edition Libri Illustri

- Editiones Reales Sitios S. L.

- Éditions de l'Oiseau Lyre

- Editions Medicina Rara

- Editorial Casariego

- Editorial Mintzoa

- Editrice Antenore

- Editrice Velar

- Edizioni Edison

- Egeria, S.L.

- Eikon Editores

- Electa

- Emery Walker Limited

- Enciclopèdia Catalana

- Eos-Verlag

- Ephesus Publishing

- Ernst Battenberg

- Eugrammia Press

- Extraordinary Editions

- Fackelverlag

- Facsimila Art & Edition

- Facsimile Editions Ltd.

- Facsimilia Art & Edition Ebert KG

- Faksimile Verlag

- Feuermann Verlag

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- Franco Cosimo Panini Editore

- Friedrich Wittig Verlag

- Fundación Hullera Vasco-Leonesa

- G. Braziller

- Gabriele Mazzotta Editore

- Gebr. Mann Verlag

- Gesellschaft für graphische Industrie

- Getty Research Institute

- Giovanni Domenico de Rossi

- Giunti Editore

- Goldenmark Librarium

- Graffiti

- Grafica European Center of Fine Arts

- Guido Pressler

- Guillermo Blazquez

- Gustav Kiepenheuer

- H. N. Abrams

- Harrassowitz

- Harvard University Press

- Helikon

- Hendrickson Publishers

- Henning Oppermann

- Herder Verlag

- Hes & De Graaf Publishers

- Hoepli

- Holbein-Verlag

- Houghton Library

- Hugo Schmidt Verlag

- Idion Verlag

- Il Bulino, edizioni d'arte

- ILte

- Imago

- Insel Verlag

- Insel-Verlag Anton Kippenberger

- Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses

- Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

- Introligatornia Budnik Jerzy

- Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana - Treccani

- Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini

- Istituto Geografico De Agostini

- Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato

- Italarte Art Establishments

- Jaca Book

- Jan Thorbecke Verlag

- Johnson Reprint Corporation

- Johnson Reprint Corporation

- Josef Stocker

- Josef Stocker-Schmid

- Jugoslavija

- Karl W. Hiersemann

- Kasper Straube

- Kaydeda Ediciones

- Kindler Verlag / Coron Verlag

- Kodansha International Ltd.

- Konrad Kölbl Verlag

- Kurt Wolff Verlag

- La Liberia dello Stato

- La Linea Editrice

- La Meta Editore

- Lambert Schneider

- Landeskreditbank Baden-Württemberg

- Leo S. Olschki

- Les Incunables

- Liber Artis

- Library of Congress

- Libreria Musicale Italiana

- Lichtdruck

- Lito Immagine Editore

- Lumen Artis

- Lund Humphries

- M. Moleiro Editor

- Maison des Sciences de l'homme et de la société de Poitiers

- Manuscriptum

- Martinus Nijhoff

- Maruzen-Yushodo Co. Ltd.

- MASA

- Massada Publishers

- McGraw-Hill

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Militos

- Millennium Liber

- Müller & Schindler

- Nahar - Stavit

- Nahar and Steimatzky

- National Library of Wales

- Neri Pozza

- Nova Charta

- Oceanum Verlag

- Odeon

- Omnia Arte

- Orbis Mediaevalis

- Orbis Pictus

- Österreichische Staatsdruckerei

- Oxford University Press

- Pageant Books

- Parzellers Buchverlag

- Patrimonio Ediciones

- Pattloch Verlag

- PIAF

- Pieper Verlag

- Plon-Nourrit et cie

- Poligrafiche Bolis

- Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg

- Prestel Verlag

- Princeton University Press

- Prisma Verlag

- Priuli & Verlucca, editori

- Pro Sport Verlag

- Propyläen Verlag

- Pytheas Books

- Quaternio Verlag Luzern

- Reales Sitios

- Recht-Verlag

- Reichert Verlag

- Reichsdruckerei

- Reprint Verlag

- Riehn & Reusch

- Roberto Vattori Editore

- Rosenkilde and Bagger

- Roxburghe Club

- Salerno Editrice

- Saltellus Press

- Sandoz

- Sarajevo Svjetlost

- Schöck ArtPrint Kft.

- Schulsinger Brothers

- Scolar Press

- Scrinium

- Scripta Maneant

- Scriptorium

- Shazar

- Siloé, arte y bibliofilia

- SISMEL - Edizioni del Galluzzo

- Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología

- Société des Bibliophiles & Iconophiles de Belgique

- Soncin Publishing

- Sorli Ediciones

- Stainer and Bell

- Studer

- Styria Verlag

- Sumptibus Pragopress

- Szegedi Tudomànyegyetem

- Taberna Libraria

- Tarshish Books

- Taschen

- Tempus Libri

- Testimonio Compañía Editorial

- TGB Limited Editions

- Thames & Hudson

- Thames and Hudson

- The Clear Vue Publishing Partnership Limited

- The Facsimile Codex

- The Folio Society

- The Marquess of Normanby

- The Orphan Hospital Ward of Israel

- The Richard III and Yorkist History Trust

- The Warburg Institute

- Tip.Le.Co

- TouchArt

- TREC Publishing House

- TRI Publishing Co.

- Trident Editore

- Tuliba Collection

- Typis Regiae Officinae Polygraphicae

- Union Verlag Berlin

- Universidad de Granada

- Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden

- University of California Press

- University of Chicago Press

- Urs Graf

- Urs Graf Verlag

- Vallecchi

- Van Wijnen

- VCH, Acta Humaniora

- VDI Verlag

- VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik

- Verlag Anton Pustet / Andreas Verlag

- Verlag Bibliophile Drucke Josef Stocker

- Verlag der Münchner Drucke

- Verlag für Regionalgeschichte

- Verlag Styria

- Vicent Garcia Editores

- W. Turnowski Ltd.

- W. Turnowsky

- Waanders Printers

- Wiener Mechitharisten-Congregation (Wien, Österreich)

- Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft

- Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft

- Wydawnictwo Dolnoslaskie

- Xuntanza Editorial

- Zakład Narodowy

- Zollikofer AG